It Is Not You, Patti Smith, but Clearly Me

By Ben Fulton

December 12, 2025

Long ago, in the days of vinyl LPs, it used to be that rock and pop music aficionados argued in horror and disbelief about the merits of their favorite bands, performers, and songwriters in the aisles of record stores a la Nick Hornby’s 1995 novel and 2000 film adaptation, High Fidelity. Today, that horror and disbelief consists of watching in helplessness as streamer algorithms point your next song selection toward the Cure or Love & Rockets just because you cued up a raft of Joy Division.

There exists another horror that stalks the souls of such people: the blind spot of an artist everyone enjoys by almost unanimous verdict, if not also by critical consensus, that escapes you entirely.

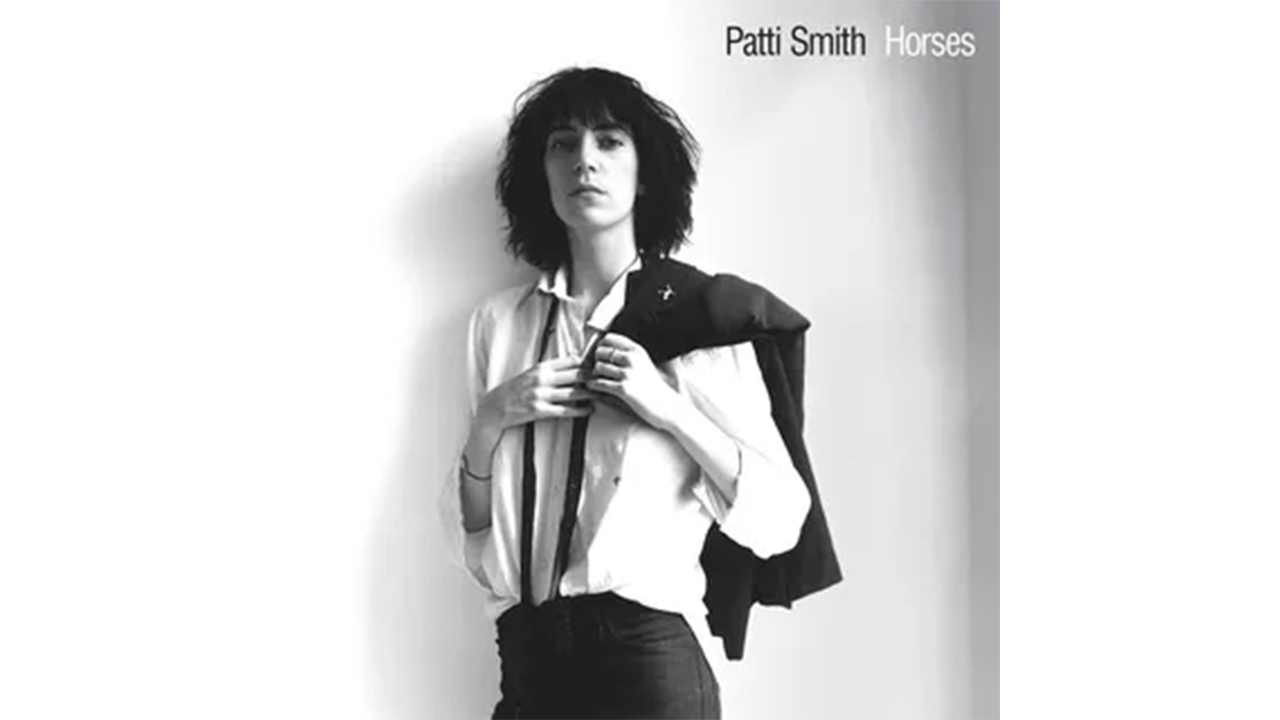

There are bands of hallowed status in the rock pantheon I loathe—Pink Floyd and the Who, foremost among them—but for whom I can also explain why they are deserving of scorn. Then there are artists I can listen to in lukewarm admiration, but remain clueless as to why they have attained godhood status. English singer and songwriter Richard Thompson is the stereotypical example of a rock icon critics adore, but before whom the public collectively shrugs. Patti Smith, currently celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of her acclaimed 1975 debut LP Horses, fits none of these bills. The hipsters have always loved her music and personality. Ditto for the critics. For my part, I can enjoy her music like a daydream at the bus stop. Certainly, it is interesting and pleasant enough. It is just that I would rather be headed somewhere else than standing next to a song Smith is singing.

To even state as much, though, feels not just transgressive before those who enjoy her music and legacy. Even so, and knowing full well that Smith’s fans would spend less than a second scoffing at my opinion, I feel a certain shame in even saying so. “Patti Smith? The Patti Smith of NYC punk-and-art-scene legend? Who dated photography legend Robert Mapplethorpe? Whose debut album was produced by none less than underground music legend John Cale? How on earth did you get so insanely dull!?”

At least my indifference, ambivalence, and sheer casual neglect of Patti Smith is draped in full knowledge that, when faced with a critical consensus as overwhelming as hers, the fault lies in my stars, and my stars alone. I know there must be something wrong with me. It is just that I cannot diagnose it, let alone point to where the gaping fault in my taste resides.

I first purchased Horses somewhere in 1985, too late by at least a decade to say I understood its seismic place in the NYC punk-scene zeitgeist, but early enough to leap light years ahead of everyone still listening to metal bands in the mid-1980s. Smith’s sly vocal stylings, a crafty mix of what we now call “slam poetry” and verse-chorus-verse singing from the voice box as opposed to the diaphragm, still count as lyrical grenades. The listener wants to know who this “Johnny” is, and of what she speaks. We empathize with Smith when she extemporizes over the cresting improvisations of her band in “Free Money.” We sway along to “Kimberly.” But when all was said and done, and my record stylus looped over the end of the second side of Smith’s LP, was I transformed in the same way as having listened to the LP Marquee Moon by Television, Smith’s brothers in arms in the NYC punk scene? Was I adrenalized in the same way that the Ramones out-rocked well, basically every other punk band, despite their monotony? No, I was not. To make matters worse, I was not nearly as affected by Smith as many other female artists she was compared to at the time. This is not to count Smith unworthy of comparison to anyone, regardless of gender. It is merely to recall that the standards of comparison back then were sexist to a degree that pales to our here and now, when Taylor Swift and Beyonce dominate every measure of pop-star success. Maybe Joni Mitchell could be an insufferable waif with her gentle voice and sappy-strummed acoustic guitar. At least before Mitchell’s music, I would be moved to cry like a baby or dance like a fool.

As everyone who follows the literary world knows, Smith reached a second zenith with her 2010 memoir, Just Kids. Eager again to find the key to her appeal that somehow eluded me, I devoured Smith’s book in less than three days. It captures all the grit and struggle of the artist’s life in ramshackle, crime-ridden New York City, when rent was still possible for non-billionaires. But as Smith’s narrative became bogged down in descriptions of various bohemian figures and famous artists who once inhabited the city’s art districts and storied apartment buildings and hotels, perhaps Just Kids captures that lost spirit a bit too well, or at least too long for readers who, as they say, “had to be there.” Smith comes across as wholly amenable, maybe even a bit too polite for her future reputation as a punk rocker. For those who have never dated a closeted gay person, which is probably most of us, she distills the confusion and heartache of dating someone so (in)famous as Mapplethorpe. Mostly, though, I was shocked to learn that Mapplethorpe flushed a stolen William Blake print down the toilet during their years as roommates. Just Kids leaves a lasting impression of Smith as a bohemian figure par excellence, which she most certainly was, is, and shall remain. There is no need for shame at not “getting” her, only sadness.

And yet, years after listening to Horses in desperate replays to discover what I was missing, that sadness lingers. I am left out. I was never invited to Smith’s party, and maybe never will be. Patti Smith, the Mother Theresa of NYC punk and the female progenitor in waiting to every future punk female figure and Riot Grrrl, will never be mine to appreciate. Sometimes we come across news reports so sad, photographs so jarring, or art and speech so moving, that we know we should, could, or might cry or scream in response. But we cannot. Instead, we cry or scream because we know we cannot, or will not, cry or scream. On some level, this means that Patti Smith has penetrated my soul despite assertions to the contrary. Perhaps that is what makes her “punk.” I just wish so much I could have been—maybe still can be?—“punk” alongside Patti Smith.