Guest Editor’s Note

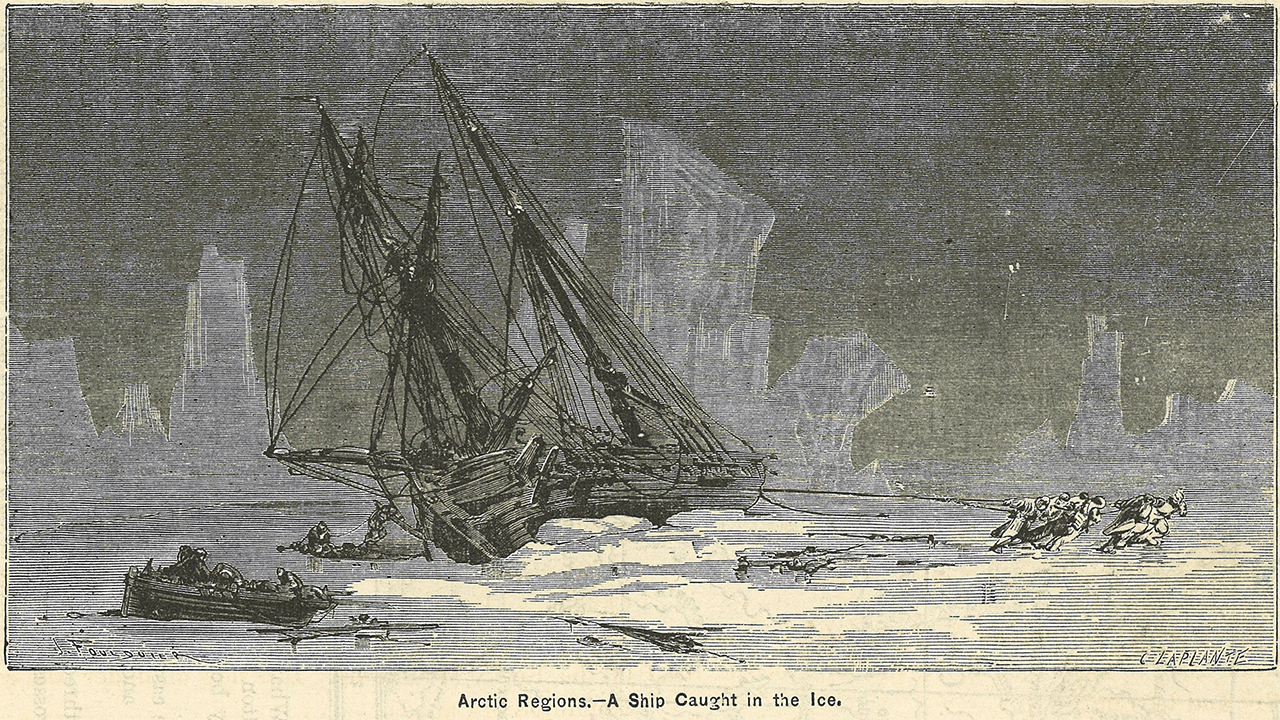

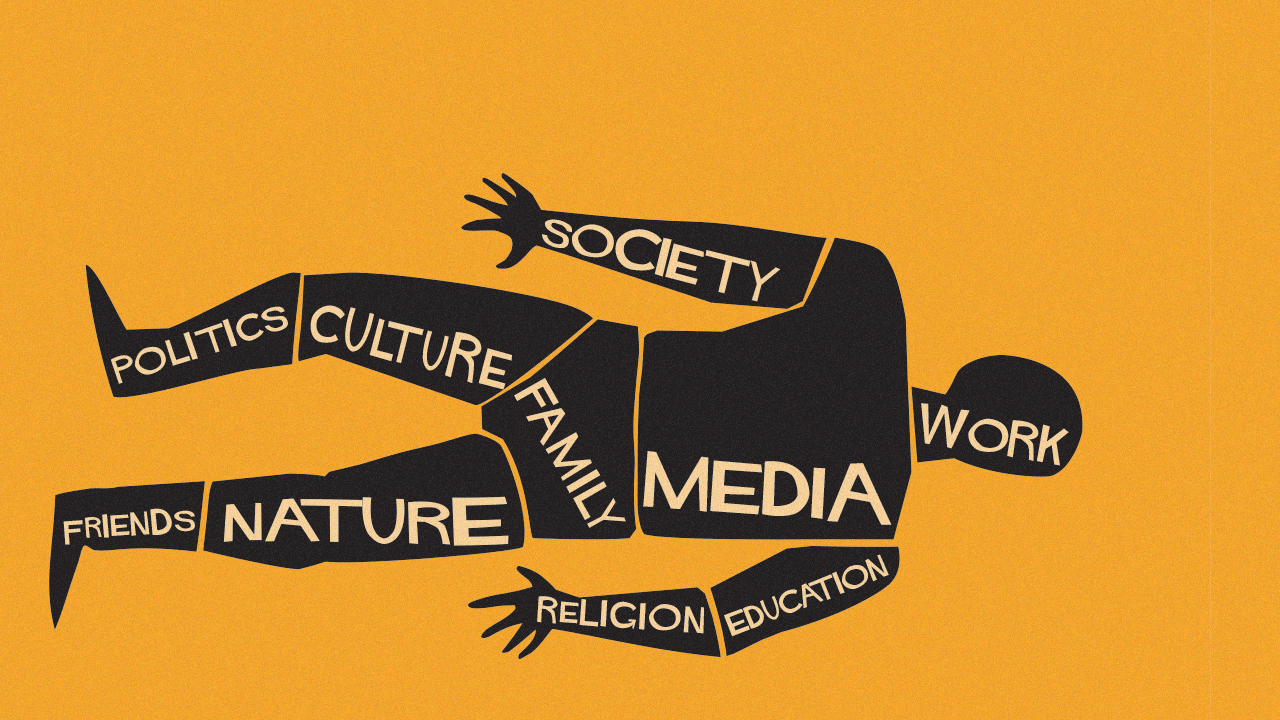

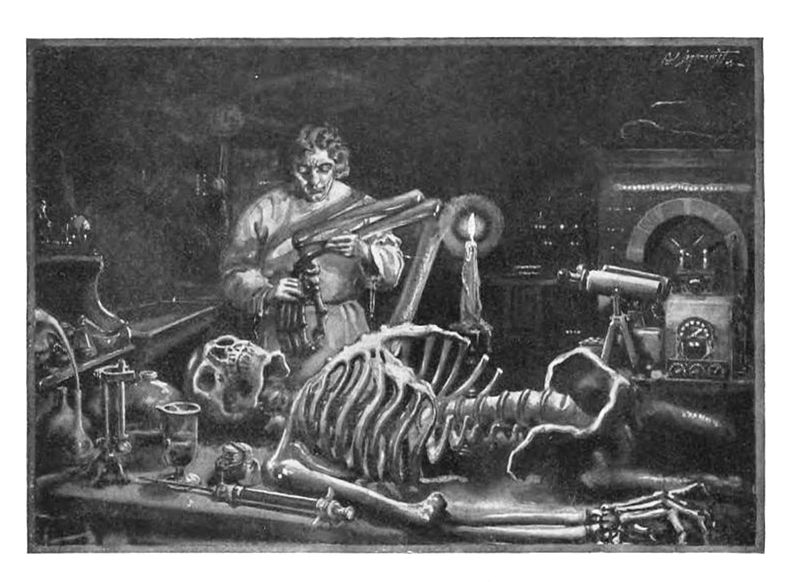

A man of science makes dead matter live yet abandons his own creation. A creature is composed of human body parts yet denied a place in human society. The epic struggle that ensues between creator and creature poses enduring questions to all of us.