At first glance, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus is hardly an obvious candidate for feminist celebration. After all, the women characters are conventional embodiments of nineteenth-century feminine virtue. Elizabeth and Mrs. Saville’s entirely domestic lives function as the foils for the imaginative bravery of Victor and Walton, whose hubristic actions drive the plot. Even without agency, the major female characters in the novel meet premature and violent death. Their oftenwise council and cautions are studiously ignored by the male protagonists at everyone’s peril. As if that were not enough, the project motivating the book is an effort to render women irrelevant to human procreation!

While Frankenstein is not Shelley’s conservative defense of the bourgeois family, a point to which I will later return, my focus here is not on the specific dynamics internal to the text. Instead, I explore what it means for Frankenstein to be Mary’s monster. To do this, we will turn our attention first to biographical dimensions of Mary Shelley’s life, including her relationship to her children, her peers, her lover-turned-spouse, and her radical parents, to see how they inform the quality and character of her reflections on birth. From there, we will consider Mary Shelley’s/Victor Frankenstein’s highly unique creature and the significance of Mary Shelley undertaking the experiment of creating Victor Frankenstein.

These three strands of exploration come together to address a straightforward question. Many have claimed that Victor Frankenstein and his creature, typically blended into one under the name Frankenstein, are among the most significant monsters of the Euromodern world. They are significant in the sense that they are visited and revisited by scholars and artists because the dilemmas the characters embody continue to be meaningful. As Joyce Carol Oates commented about the novel in 1984, “[i]t is a measure of the subtlety of this moral parable [that] it strikes so many archetypal cords and suggests so many variant readings.”1 What does it mean for Frankenstein and his creature to have been born of a 19-year-old, pregnant woman?

Mary Shelley’s experiences as a mother, sister, wife, and daughter were, after all, marked fundamentally by the costs of making unconventional decisions. In this sense, her biography mirrored her political times.

Mary Shelley, like her pioneering feminist mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, undertook to live life on her own terms. As literary critic Mary Poovey puts it: “The events and emotions that Mary Shelley experienced in her young adulthood were, to say the least, not the sort that middle-class moralists sanctioned or even openly discussed…[Shelley] lived almost completely outside the conventional definitions of what a woman should be or do.”2 While she would not renounce this experimentation, or even regret the principle that underlay it, Shelley was aware of the depths of difficulty involved in trying to build a life and relations that, in reflecting values outside of existing norms, elicited public scorn. Her experiences as a mother, sister, wife, and daughter were, after all, marked fundamentally by the costs of making unconventional decisions. In this sense, her biography mirrored her political times: after their defeat of Napoleon, the nationalism of the English took a conservative turn expressed in a rejection of all radical political ideas, including feminism.3

Death, moreover, remained a constant theme. Mary Shelley’s first child, a premature daughter, died after two weeks of life. She would lose two more: Clara to heat exhaustion in Venice and William to malaria in Rome, between the publication of the first and second editions of Frankenstein. While the fourth child, Percy Florence, reached adulthood, the miscarriage of the fifth in 1822 nearly killed Mary Shelley. Even by the infant mortality rates of her day, this was excessive.

The proximity of death also touched her relatives and peers. Mary Wollstonecraft had given birth to one other child, a daughter, Fanny Imlay, who was Mary’s sister. Fanny was found dead from an overdose of laudanum at age twenty-two. The first spouse of Mary Shelley’s lover-turned-husband, Percy Shelley, took her life only two months later at twenty-one, drowning herself in the Serpentine River. It was therefore perhaps not surprising that when Mary and Percy Shelley did marry, the British courts denied them custody of the two children born through his first marriage.

As for her own mother, it was complications resulting from Mary Shelley’s birth that killed Mary Wollstonecraft. Shelley’s father, William Godwin, the prominent anarchist political theorist and novelist, would never completely recover from the loss. Mary described herself as excessively and even romantically attached to her emotionally remote father, who sought to cultivate her talent while admitting to not knowing her well. Godwin remarried, but he chose a woman who proved a highly “uncongenial stepmother” to Mary. When she eloped at sixteen with the married atheist and radical Percy Shelley, though a critic of the institution of marriage, Godwin strongly disapproved. To one of his creditors he wrote that he could “not conceive of an event of more accumulated horror” than his daughter’s marriage to his mentee and then benefactor Percy Shelley. Mary’s life with Percy would not last very long either. He drowned on a boating trip a month before turning thirty and only six years after marrying Mary.4

Finally, Shelley was anxious to be both a worthy daughter to her historic parents and a meritorious wife to her esteemed husband, who is widely considered among the greatest lyric poets to use the English language. She reflected in her journal in 1838: “I was nursed and fed with a love of glory. To be something great and good was the precept given me by my Father: Shelly reiterated it.”5 Mary spent considerable time studying the written works of her parents, often beside the grave of her mother. She also loved and resented Percy Shelley’s urging that she live up to the standards they had set by developing her own potential. While she appreciated his confidence in her abilities, she desperately feared being disappointing. Put differently, while Mary Shelley shared with her family a distinct urge to create both in her personal life and through her writing, she was also painfully aware that the process of trying to bring new ideas and social arrangements into being was contingent and uncertain, often culminating in catastrophe, failure, or death.

While Mary Shelley shared with her family a distinct urge to create both in her personal life and through her writing, she was also painfully aware that the process of trying to bring new ideas and social arrangements into being was contingent and uncertain, often culminating in catastrophe, failure, or death.

Similar themes inform the life of Mary Shelley’s creature, whose wild uniqueness has been somewhat lost to us because Frankenstein has become such a ubiquitous myth. Much of the creature’s distinctiveness is borne of his paradoxical character. Lumbering and large, stronger and more agile than his creator, he also possesses features that have historically been considered feminine or female. After all, while Victor devotes meticulous attention to the details of the creature’s flesh and bodily construction, he shudders and flees as the creature opened its eye and looked back, announcing that it too possessed a point of view and its own inner, subjective life. In spite of all of the creature’s efforts, through word and deed, to gain acceptance, others refuse to look beyond his hideous appearance which, he is told repeatedly, over-determines who he is and the value he may possess. Although sought and envisioned in the form of a companion wife-creature, the creature knows that he will only have a social existence through a romantic relationship. Without that, he can only live invisibly, stuck in his own self-loathing and destructive behavior, all of which is undertaken to elicit a response from a father who refuses to recognize him. As Poovey has argued, the creature is a symbolic vehicle for another’s desire. In this case, his literal embodiment is first exposed and then exiled. It is hard not to recognize the autobiographical likenesses of Shelley and her creature: a motherless woman creates a motherless creature who fears that he unwittingly destroys all that he touches.6 Mary Shelly breathes life into the paradox of a giant creature whose situation resembles that of a nineteenth-century woman through one of the text’s most enduring features: her decision to give the creature, typically called “the monster,” a voice. And it is not just any voice. The creature’s speech is articulate and compelling, allotted space to rival and equal the narratives of Victor and Walton. Still this textual room should not be misunderstood: Frankenstein’s readers know that the creature’s voice is one that we are not supposed to and do not typically hear. It resembles the voice of an individuated slave or a colonized man or woman or of a disabled person. The creature, in other words, would typically be spoken of or spoken for. It would not be treated as having the wherewithal to use language to intervene in the interpretation of an unequally shared reality.

Mary Shelly breathes life into the paradox of a giant creature whose situation resembles that of a nineteenth-century woman through one of the text’s most enduring features: her decision to give the creature, typically called ‘the monster,’ a voice.

As had been so with her mother and would be true of many women intellectuals after her, Mary Shelley’s detractors and critics considered her a monster. Not only had she eloped with a married man and atheist, like her mother, she had become pregnant outside of marriage. For those who were sure that this was both sinful and unnatural, the ensuing tragedy would have read as divine retribution. But Mary Shelley went further. As a mother, her conventional role would be limited to the private sphere or to a highly mediated expression of agency whereby her self-expression was exhausted through the cultivation of others whose actions would redound to her. With her lover-turned-husband’s urging and support, she did not only give birth, she also created or, through her pen, brought new ideas into public existence. Shelley did often describe her writing process as being propelled by forces outside and beyond her, in an effort that Mary Poovey construes as successfully combining her pursuit of literary worthiness with an equally intense desire for approval in a society that disparaged female ambition.7

When so propelled, at least with her first novel, what was her focus? In Frankenstein, Mary Shelley weaves a tale that directly inverts her own supposed monstrosity as a woman writer. If she defies her gendered nature by undertaking to live and work as an intellectual, what does Victor Frankenstein do? He is a man who, with unlimited access to advanced education and a public life, holes himself up in asocial isolation, literally turning his home into his lab. (It is true that he is described as having been overtaken by an obsessiveness that could be read as a bout of madness, which complicates the ascription of what he undertakes as a deliberate choice.) Rather than creating on the scholarly model of his day, which would have demanded interacting with existing researchers and their scholarship to contribute a novel idea or an unprecedented form of experimentation that might create a legacy with intellectual heirs, Victor sought literally, stitch by nasty stitch, to make life.8 The metaphorical parenting in which professors engage through mentoring and training subsequent generations of scholars and teachers, it would seem, was not enough. Once Victor achieves his aim, however, he spurns the independent (and thereby monstrous) fruit of his labor and the parenting that should have followed.9 Once made, even Victor’s repeated rejection and ongoing harsh neglect cannot free him from the relationship that he has single-handedly brought into being. Put slightly differently, Mary Shelley, the published author who will support herself and her son through her own writing, here considers a man who, galvanized by the pursuit of immortality, turns from a transcendent model of creation to a factical one of birth; from being seminal through crafting timeless ideas to doing the isolated, private labor of making a human being. Lastly, Shelley has the temerity, in making this reversal the subject of her work, to stimulate searching sympathy not for Victor but for the living creature and multifaceted damage he spawns.

In this sense, to return to where we began, literary scholar Kate Ellis is absolutely right that Mary Shelley continues a project inaugurated by her mother. Like Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley stresses the indispensability of intimate and nurturing relations to the creation of societies that will not continue callously to waste human potential. She also illustrates what her mother had argued in the form of a political treatise, that actually existing ways of organizing family relations, reproduction, and child-rearing do not cultivate such indispensable affection. Instead, as depicted in Frankenstein, they were the private spaces of refuge that men must leave to seek their glory. As Ellis writes, “Shelley continued to explore the damaging effects, on men and women both, of a gendered division of labor built upon separation of ‘home’ and ‘world.’ Victor Frankenstein’s idyllic family life does not allow for the expression of anger or ambition, and his inability to control the monster he so furtively creates arises. . . from the way in which the monster embodies ‘the repressed,’ that which has no place in bourgeois family life.”10 Seclusion and isolation, the prerequisites for keeping the world at a safe distance from the bourgeois family, destroy men and women alike. Rather than endorsing this ideal, then, Frankenstein offers an unsparing exploration of its dangers.

In Frankenstein, Mary Shelley weaves a tale that directly inverts her own supposed monstrosity as a woman writer. If she defies her gendered nature by undertaking to live and work as an intellectual, what does Victor Frankenstein do?

Pivotal to this challenge is the essential place of the De Lacey family in the Frankenstein text. Although they are not ideal, they, and especially Safie, stand in sharp contrast to the men and women in Victor’s family. The De Laceys are French refugees who lost their wealth and prestige because they plotted the escape of Safie’s Turkish father from his xenophobic and discriminatory imprisonment in Paris. Safie’s mother, who had been a Christian Arab seized and made a slave by the Turks, had taught her daughter to “aspire to the higher powers of intellect and an independence of spirit forbidden to the female followers of Mahomet.”11 The De Lacey grandfather is disabled. Specifically, he is blind. When the creature first encounters them, the family is poor and, without Safie, Felix is perpetually sad, but it does not practice a strict gendered division of labor. Instead they work very hard and thrive and lose together. It is through coexisting beside them and their cottage that the creature develops the ability to understand and use language and, through observing them and reading books that he finds, contextualizes and makes sense of his own suffering in and through its relationship to other people who face brutality, exile, and colonization. The juxtaposition of the creature’s life with theirs suggests that it is political machinations that produce people and groups that are first made vulnerable and then disavowed. Hidden in plain sight, the failure to understand the creation of people’s problematic circumstances leads to distorted understandings of the actual nature of responsibility. It is no accident that, as the creature lives in hiding in the orbit of the De Lacy family, the text depicts an instance of invisible labor. As slaves and servants and wives and colonized people might, the creature prepares and leaves wood for the De Lacey family. In his case, he does it as an expression of love and an effort to help them through difficult times. While they appreciate this gift, they literally do not know who is producing it. The flipside of this condition is the fate that befalls the Frankenstein family’s servant, Justine. If unmerited credit is often claimed for the labor of the invisible, they are also often the first to be blamed with impunity, regardless of their actual guilt or innocence. Whether unable or unwilling to tell others of the existence of the creature and the violence of his neglect, Victor allows Justine to be hung for a murder she did not commit.

Like Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley stresses the indispensability of intimate and nurturing relations to the creation of societies that will not continue callously to waste human potential.

Finally, there is also, in Frankenstein, a meditation on how particular approaches to creation involve a sense of entitlement to the dead, or at least to their bodies. As Shelley was writing, newspapers documented the robbing of graves to supply anatomists and medical students with body parts.12 In the classic mode of refugee turned settler, Victor, who feels powerless in the face of the death of his mother, rummages through the dead relatives of others in his effort to find a triumphant reprieve. Meanwhile, the creature speaks from the shadows of those who have not given their consent to be experimented upon. As historians Lester Friedman and Allison Kavey note, he “speaks to the millions of people who have been and may yet be tormented in some way when, to satisfy our desire to know more, we practice science on those who cannot defend themselves—the weak, the poor, the young, the incarcerated, the disenfranchised, those from unpopular minority groups, and even the dead.”13

The relation that Victor exemplifies to both the unborn and the dead is especially fascinating when considered in light of the death of Mary Shelley’s mother. Wollstonecraft had been in excellent health and had given birth to Fanny with no complications. With Mary Shelley, Wollstonecraft had elected to have the baby at home with the assistance of a midwife. When she did not expel the placenta, the midwife summoned a doctor who did not wash his hands before pulling it out piece by piece. Wollstonecraft would die ten days later.

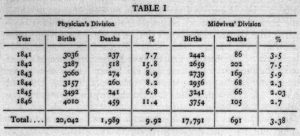

Childbed fever mortality statistics

Medical Classics, vol. I, ed. Emerson Kelly (Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1936). Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

The iconic nature of this particular instance of mother and daughter should not eclipse the epidemic scale of the “puerperal fever,” which killed Wollstonecraft. Beginning in the seventeenth century with the rise of lying in hospitals and male obstetric practice in cities of Europe, in one year, in the French province of Lombardy, there was not a single woman who survived childbirth. Originally designed for the poor who could not pay to have a doctor visit their homes, European hospitals were typically unsanitary and overcrowded, full of unwashed linen and organic waste.14 When the physician Oliver Wendell Holmes visited Vienna in 1840, he observed that the mortality rates were so high that women were often buried two in a coffin to hide the actual numbers of death. While many women knew that childbirth in hospitals was extremely dangerous and tried to avoid them, the majority of the poor were required to avail themselves of these services as these clinics were the developing sites of medical teaching and experimentation; their lives were treated as a legitimate sacrifice to the project of creating modern healthcare institutions.

Although fatalistic indifference to the exponential rise of maternal deaths persisted as the norm, a handful of physicians sought to understand the cause. In 1795, Alexander Gordon observed that the infection only occurred with women treated by practitioners who had previously attended patients with the disease. There was no mystery: these were instances of contagion communicated by the physician. When, fifty years later, Holmes demonstrated that it was physicians who were carrying life-threatening diseases from patient to patient, the response was outrage at the suggestion that physicians’ hands were unclean! After all, it was midwives who supposedly were unsanitary. Although Holmes was attacked as a self-seeking opportunist, the essay outlining his findings later became a medical classic. Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis, a Viennese physician, also faced great professional penalties for demonstrating what is now considered obvious. In 1861 he showed that women who gave birth in the street had a lower mortality rate than those who did in the clinic. The issue with the clinic was the physicians who, like Victor Frankenstein, dealt with cadaveric particles that could not be removed through ordinary hand-washing. As a result, these particles were taken from the dissecting room directly into the uteruses of delivering women. While the child could survive, this was a death sentence for the mother. Semmelweis mounted a campaign for all physicians and medical students to wash their hands in chlorinated lime on entering a labor room. While the positive results were immediate, Semmelweis was professionally discredited by powerful physicians who assured he would never work in Vienna again.15

As a divine warning and portent of what to come, she was, in the etymological sense, a monster. Differently from her mother, who used the political tract to challenge the incompleteness of a bourgeois revolution through taking on all of the remaining vestiges of illegitimate power and unmerited status, Mary Shelley’s writings confronted the vortex of attendant social and personal costs for those who deliberately sought sexual freedom, radical democracy, and women’s rights …

To think that such simple measures could have spared the life of Mary Wollstonecraft that ended at a mere thirty-eight years, along with so many others!16 Many readers of Frankenstein would likely compare the cavalier work of obstetricians to Victor Frankenstein and to the voyaging spirit of Walton. However, I think the conclusion is somewhat different.

One would expect historic monsters to bequeath historic monsters. Like her mother, Mary Shelley lived the life of a woman intellectual. Engaging public issues through her writing she offered a multifaceted view of the existing world through the speculative lens of other social and political possibilities. As a divine warning and portent of what to come, she was, in the etymological sense, a monster. Differently from her mother, who used the political tract to challenge the incompleteness of a bourgeois revolution through taking on all of the remaining vestiges of illegitimate power and unmerited status, Mary Shelley’s writings confronted the vortex of attendant social and personal costs for those who deliberately sought sexual freedom, radical democracy, and women’s rights, especially in a period of politically conservative backlash. In a way profoundly informed by her own experiences of both birth and creation, she invites us to face the radicality of our responsibility for our powers to bring new lives and worlds into being.