Is It Time to Drop the Penny?

October 24, 2024

Thoughts are pricy these days; a penny will only buy ambivalence. Should our nation’s tiniest coin be preserved or officially abandoned? It has shaped our figurative language, our notions of thrift, our attitudes toward money. Yet we are a practical people, and it costs well over one cent to mint a penny (1.82 at the moment but 2 cents at its peak). You would think we would have enough of them already, but the U.S. Treasury is forced to keep minting more because two-thirds of the pennies handed out by banks are never seen again. Nobody bothers to spend them, so there are about 240 billion pennies stuffed into ceramic pigs or sliding around in junk drawers across the nation.

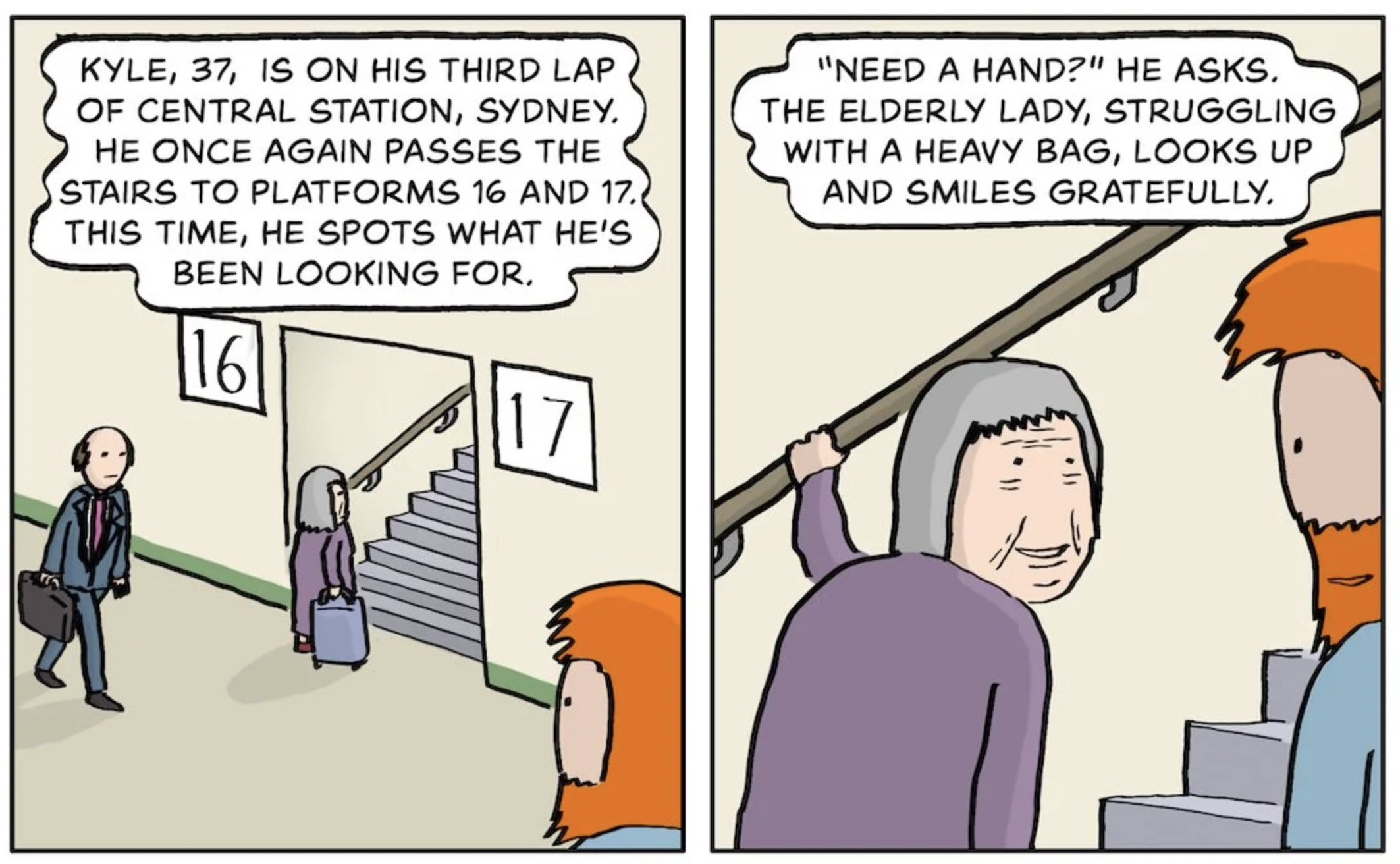

My mother-in-law made it a point to spend hers. Waving away my quarter, she counted them out one by one at the grocery store, her fingers fumbling and the line lengthening behind us. The checker smiled with disciplined patience, but when Jo swept the pennies closer and recounted to be sure, my brain imploded.

As a child, though, I found pennies marvelous. One of my jobs was to feed them into tight paper rolls for my great-aunt to take to the bank, and when they spilled from her jar, the shiny copper glinted in the sunlight, a warm pale bronzy orange that seemed happier than the silvery gray coins supposedly “worth” more.

Now I learn that pennies have not been solid copper since 1856, when they were adulterated with nickel to save a few cents. Nine years later, the penny-pinchers at the Treasury subbed in tin and zinc. With World War II’s copper shortage, pennies were made of steel coated in zinc. And since 1982, they have been 97.5 percent zinc, coated in a measly 2.5 percent copper because in America, surfaces are what matter.

Why should we keep them at all, in a time when a handful of penny candy costs five bucks? The penny was inspired, if you trace the history back far enough, by the denarius, a Roman coin that was worth a laborer’s daily wages. Ha. The penny comes nowhere near. Yet it is the only American coin that has been continuously minted and circulated. The first U.S. coin was the Fugio cent, or Franklin cent, supposedly designed by Ben Franklin himself. “A penny saved,” he insisted, “is a penny earned.”

And that penny, my friend, will buy you…nothing. Saving pennies is about as satisfying as scraping up crumbs from a cookie jar and, a few months later, mashing them together with spit and popping the little ball in your mouth.

So how far do we go with sentiment? I can usually go pretty far. Pennies were how I came to know the heroic Abe Lincoln, who was the first U.S. president pictured on a coin. Now I learn that he was only stuck there after an unfortunate series of designs: a linked chain that was supposed to symbolize liberty but instead suggested the bondage of slavery to many; a succession of women-with-flowing-hair-symbolizing-Liberty; an “Indian head” in feathered headdress. So much oppression, disguised as liberty.

Back in the golden age of retail, Rowland Macy stole Paris’s trick of pricing with odd-number centimes, which makes the total sound (to the innumerate) like it rounds down to the lower franc. So what will we do with all those $9.97 items if we ditch the penny? Retailers will of course round up, gouging consumers with tiny nicks that eventually add up. Just as kids collecting pennies for a charity adds up, often raising hundreds of dollars. Because who is going to deny a wide-eyed child a few unwanted pennies?

I dither, unable to decide the penny’s fate. Too much passion is involved. Americans for Common Cents are convinced that rounding to the nickel will hurt poor people. They offer studies and scholars to prove it, while other studies and scholars say that everybody would break even, and even people with low incomes are making cashless transactions these days. Pennies cost more than a penny to make, but we would be rounding up to the nickel, which is made at an even greater loss. (Also, pennies at their costliest were only 2 cents. Donald Trump flipped the deal, minting “official” coins he sells for $100, though they contain only $30 worth of silver.)

Back to the penny, which takes time to count out (would we spend less if we used them more?). Time is, at least potentially, money. Citizens to Retire the U.S. Penny (who seem no longer viable themselves, with a defunct website and social media that stopped in 2016) once announced that we waste 120 million hours a year using pennies, at a cost of $2 billion to the U.S. economy.

Seriously? Pennies add two seconds or more to each cash transaction (and for my mother-in-law, it was several minutes), so I can buy the notion that the average consumer spends twelve minutes a year messing with them. But would I have used those twelve minutes to add to the GNP? Stats and arguments fly back and forth. The Department of Defense will not even allow use of pennies at overseas military bases, explaining that they are too heavy to ship. I roll my eyes—until I read that $100 in pennies weighs more than fifty-five pounds. Point taken.

But if we abandon the penny, what will we toss into a fountain to make a wish? Because I am damned if I will waste a quarter and then be disappointed. Pennies can be lucky, and they can be tossed. “I threw a penny,” wrote Yeats, “to find out if I might love.” When else is fate so easy to play with? Besides, my mom always told me that a penny was only lucky if you gave it away, which was a lovely early lesson. Pennies can provoke generosity without costing us much. I smile when I see the spare-change jar at the counter and add my pennies too, secretly relieved to not have to dump them into my purse. Those already there rattle around like incels in the basement, devoid of purpose and no doubt bitter about it.

An even more cynical take on that penny jar? “When people start leaving a monetary unit at the cash register for the next customer, the unit is too small to be useful,” according to Harvard economist Greg Mankiw. Sad commentary. Possibly accurate. A recent article in the New York Times Magazine yelled, “America Must Free Itself from the Tyranny of the Penny,” adding, “Few things symbolize our national dysfunction more than the inability to stop minting this worthless currency.” For Barack Obama, the penny was a metaphor for governmental dysfunction: “It’s very hard to get rid of things that don’t work.”

By that logic, maybe we should get rid of nickels, too. Dimes cost less than ten cents to make, and quarters cost less than twenty-five cents, and the seigniorage (the pretty word for that discrepancy) is used to finance the national deficit. Or why not get rid of currency altogether, as it is nearly extinct, except at the farmer’s market? I remember, as a kid, being terrified that credit cards would replace dollars and cents. Why, I am not sure; none of the grown-ups around me seemed alarmed. But kids think more concretely, and the stuff of money within my reach, first from tooth loss and then from babysitting, was green, not plastic. Today, still naïve, I feel sad to see ApplePay nudge PayPal aside. We grow attached to our methods of impoverishing ourselves.

That irrational affection might be the only real obstacle here. Who benefits from pennies, anyway? They are nearly useless as exchange, and they take up more space than they are worth. Whoever sells the zinc benefits, I suppose. Also Coinstar, which accepts the saved-up pennies and charges a service fee and transaction fee. But their volume is down, because people have stopped bringing in jars of pennies. In terms of economics and utility, the penny is dead. But in terms of symbolism and history, it is rich.

“The world is fairly studded and strewn with pennies cast broadside from a generous hand. But—and this is the point—who gets excited by a mere penny?” asks Annie Dillard, choosing pennies as analogy in her lovely essay “On Seeing.” “If you cultivate a healthy poverty and simplicity, so that finding a penny will literally make your day, then, since the world is in fact planted in pennies, you have with your poverty bought a lifetime of days. It is that simple.”

Diminish value, and there is less to bring you joy. In the blur of escalation, acceleration, super-sizing and supercharging and ramping up and amplifying and expanding, we forget that not everything is about money. Not even money.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.