In Memory of Writer Stanley Crawford

January 29, 2024

Stanley Crawford has died at eighty-six. Stan published eleven books of fiction and nonfiction, including the wonderful novella Log of the SS the Mrs. Unguentine, and the memoir A Garlic Testament: Seasons on a Small New Mexico Farm. RoseMary, his wife, passed away almost exactly three years ago.

Together they owned and operated El Bosque Garlic Farm, in Dixon, New Mexico. A friend and I visited in 2015, a highlight of my year. The following is adapted from pieces I wrote at Inside Higher Ed and in my essay collection The Age of Clear Profit.

• • •

Frenchy and I met in Phoenix and drove north out of the Sonoran Desert and up through the Mazatzal range, the Tonto National Forest, the Petrified Forest, Albuquerque, and Santa Fe. After 500 miles we arrived in Dixon, New Mexico, in the Embudo Valley, but could not find the Crawfords’ place. Dixon has fewer than a thousand residents living along a single road curving through the low mountains. There are a couple of wineries, a farmer’s market, and several art galleries and artist studios.

A Merlot sipper stood in the salesroom at La Chiripada Winery, slyly hinting at buying a case or two. I waited for his next pour to ask the server if he knew the garlic farmer Stanley Crawford. He laughed and said yeah. He said to drive out of town and at the bend hang a left on the first county road.

Stan’s first novel, Gascoyne (1966), was written on Lesbos and film-optioned by Richard Lester (Hard Day’s Night). Stan married RoseMary, an Australian journalist, on Crete; they moved to Ireland, where they had their first child, then returned to San Francisco in the late sixties. Things were so tumultuous there, he says, that when friends invited them to northern New Mexico for a visit, they stayed.

The last of the movie money was used to buy land. They built an adobe house, began to garden and then farm, and became involved in local life. When the bank required him to own more land in order to qualify for a tractor loan, he got that too. They have been at it four decades.

Frenchy and I turned left, down through an arroyo and along a dirt lane. The gate to Stan’s farm was so narrow the car barely fit. We drove up the dirt driveway, past a hillock of composted manure, tractors, freshly-tilled dirt, rows of late crops, and a Quonset greenhouse, to the house. Stan and another man were standing by a pickup, talking. One of the biggest mixed-breed dogs I have ever seen was lying in the driveway, and when we got out of the car, the dog walked straight to Frenchy, put his front paws on his shoulders, and looked him soberly in the eyes.

“Tesoro!” Stan called and apologized for the dog.

We caught up a little, and Stan walked us around the farm to see the garlic sorting-shed, the hoop house, the chicken coop, and the tower guesthouse with its ¾ cylindrical stone bay that had been, briefly, his writing studio.

“During those intense years—the 1970s… my attempts at fiction seemed rather pallid in the face of what I was actually living,” Stan told Bomb magazine. In New West he said:

Yes, we built our house with our own hands, grew our own food, kept livestock, but what I discovered in Northern New Mexico (and had been long craving) was the social, was cooperation, collaboration, and dialogue about matters political. And of course history is still very much alive here, to perhaps an unusual degree in the States. Raising children was also at the core of all this. [My character] Unguentine sought to disentangle himself from the world, from the social and political and historical, and live in the mythical world of self-sufficiency; and if this was to a certain extent an illusion I was attracted to, our early years in New Mexico quickly disabused me of it. Of course the imagination is where one can safely try out such extremes.

Stan and RoseMary drove us in their electric car to Taos for dinner. The Sangre de Cristos were topped with snow in the sunset. We had a lovely chat over Chinese food then came back down through the dark mountains, through Dixon, and as we turned to cross the arroyo for the farm, RoseMary sang, “My little road, my little road….” She seemed so happy, so vulnerable. Forty years of hard joy.

“Tesoro, my treasure!” RoseMary exclaimed as we walked into the Crawfords’ living room. She explained how she had poured the massive adobe floor herself, learning as she did it. When she said goodnight, Tesoro tried to climb on my lap; only his top-half fit. Stan talked with Frenchy and me about writers we knew and books we liked. He asked our plans for the next day and insisted we come up to the house for breakfast at 6:30. We wished him good night and walked a few yards through the garden to the guesthouse.

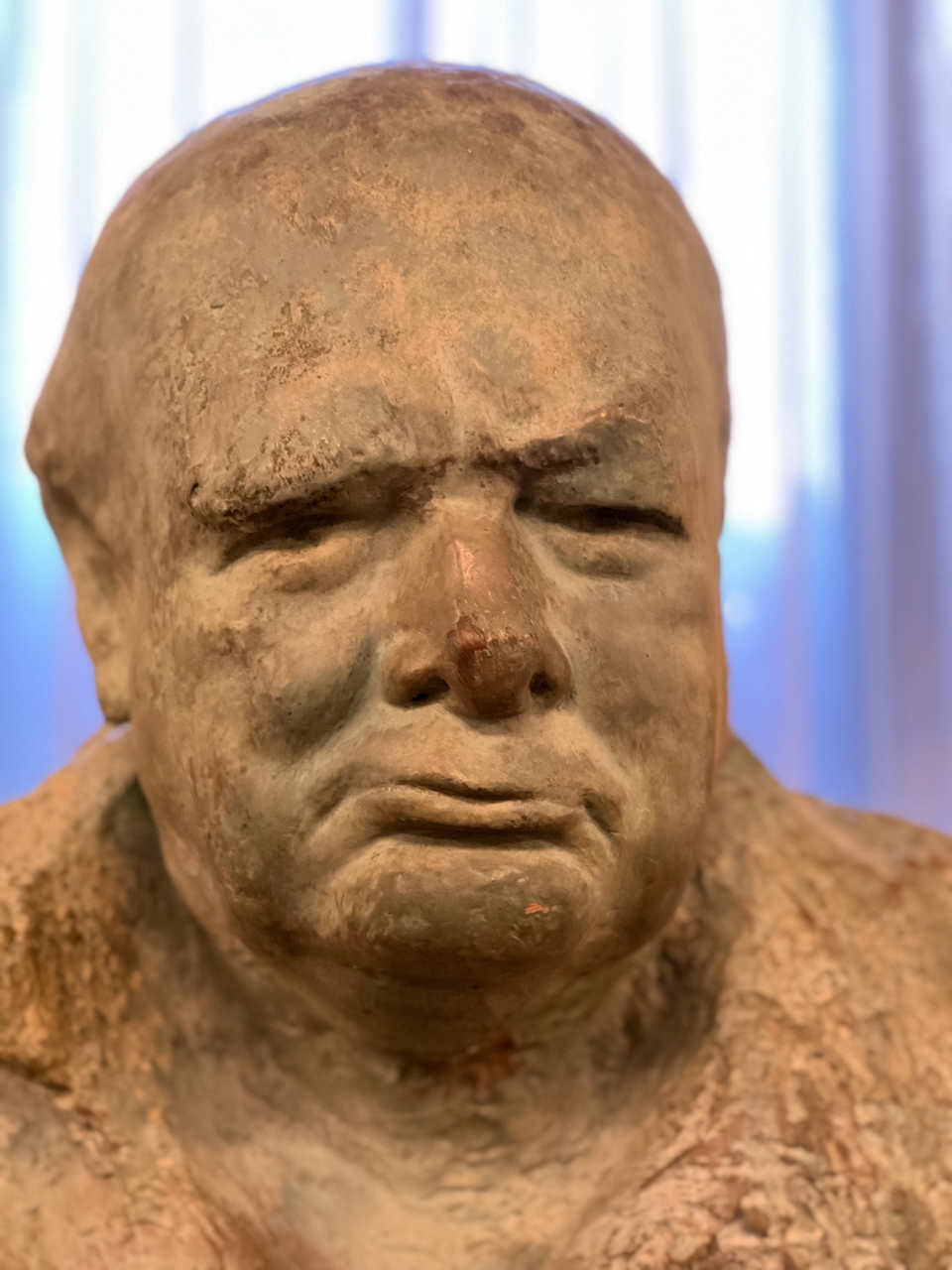

It was country-dark the next morning. There was frost, but the heavy adobe fireplace in their house was still warm from the night before. We did not want to impose but agreed to a cup of coffee. RoseMary popped in and said she was going back to bed. I took photos with Stan, and he filled a bag with garlic and shallots for us. We said goodbye, and Frenchy and I drove out through the narrow gate. None of the lights were on in Dixon, and we had a day’s drive ahead.

In A Garlic Testament Stan writes:

[T]he great danger of living in a small place, in relative solitude, in an almost resistanceless state, lies in formulating generalizations that will readily crumble elsewhere. For this reason I will take the occasional long drive…. No precise questions are answered by these trips. I am only reminded that this is an enormously wealthy and varied nation, yet also an insensitive and cruel and deadening one, and that to strive for recognition or wealth within it is a disquieting, unceasing labor that will not bring the best out of any man or woman. Better perhaps to seek the contentment of more humble work within the belly of the beast, to inhabit the Pascalian room, to chop your wood, haul your water; better perhaps to stay at home and grow your patch of garlic, and to dream in winter your subterranean dreams, which are always the same: of light, of warmth, and of liberation.