If Second Chances Are Not Free, How Much Do They Cost?

By Wen Gao

December 1, 2025

The first time I met him was during a week-long leadership training held by a national gathering of community and faith-based organizers.

When we went around the room for introductions, everyone else kept it brief, but when it came to him, he talked endlessly.

The instructor tried to move things along, but he kept going.

I was doodling on the paper, but the way he talked made me really look at him for the first time. His style was bold to me, with flashy jewelry and a brightly colored outfit.

Right away, he made a bad impression on me. He was talking over people. Later, he mentioned that he had spent time in prison. He said it so calmly, even with a hint of bragging. At that moment, I felt sure he was not someone I wanted to deal with.

During the training, I talked to him out of politeness. Strangely, he was surprisingly friendly. He listened carefully, and never interrupted. He would pull out chairs for ladies, hand someone a napkin.

I began to wonder who he actually was.

That question became clearer the second day, during the training.

Up to that point, the training had felt less like leadership development and more like being bullied. On the first day, during our introductions, the instructor had asked each of us to name a significant hero. When I said Chairman Mao, they asked, “Why would you admire a dictator?”

Their tone was not curious, it was dismissive, almost mocking. I froze. I did not know how to answer. I was the only Asian person in the room, the only foreigner, and suddenly I felt exposed, singled out in a way I could not fully explain. I told myself not to overthink it, but the moment stayed with me.

By the second day, things escalated. As I tried to ask a question in the conference room session, I raised my hand, and they told me I could not ask a question, yet everyone else spoke freely. When I finally began to cry, they told the whole room that I was “playing the woman card” to get attention.

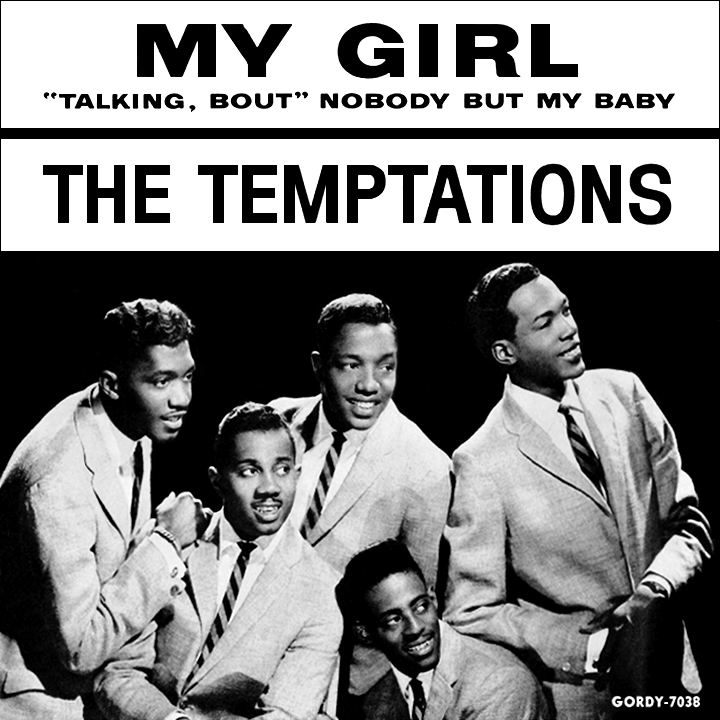

He played one of his favorite songs, “My Girl” by the Motown group The Temptations, music from his youth before he went to prison. It was a nice song but I felt a little awkward; it was late, and the music felt too loud. But he did not seem to care. He swayed his shoulders and danced softly to the song by the river.

Hearing that, my chest tightened; my heart was racing so fast it felt like it might climb out of my throat. I did not know it was a panic attack. I only knew I was shaking, numb, unable to stand, while everyone watched, waiting for me to “handle it.”

Then he stood up, the same participant I had disliked on the first day.

“You do not talk to people like that,” he said. His voice was low, steady.

I had never been defended like that before, especially not by someone I thought I should fear and someone I had decided I did not like.

That night, I fell apart. The training was held in Milwaukee, far from home, and I did not have a single friend there. After what happened, all I wanted was to leave, feeling helpless in a place that was supposed to teach us “leadership” and “empowerment.”

Later that evening, he, the same person who had stood up for me earlier that day, asked if I wanted to take a walk by the river and talk. The training site was only a short walk from the Milwaukee River. I was still shaken and needed someone to talk to, so I accepted his offer. My feelings toward him were complicated; I still did not entirely like him, but I really needed to talk.

We walked slowly along the Milwaukee River. He was a tall Black man with a tough face, the kind of person I might avoid if I passed him on the street. I was still a little cautious, but because we were in the same training and because I had been so upset that day, I trusted him enough to walk and talk.

As we walked, he started telling me his life story. He said he wanted me to know that I should not let small moments crush me. He had survived things ten times harder, and he shared his past to encourage me to stay strong. He told me he had spent fifty-one years in prison, and that he survived it. I found myself pulled into his story, distracting myself from my bad day. I had never met anyone who had spent that long in prison. Then he told me that when he was young, he killed a police officer. He did not say more, and I did not ask.

“This world changed too fast,” he said. “Back then, there were not so many cars. No smartphones.”

It sounded like he was only describing how technology changes, like missing five decades of life was just a fact, no other emotion.

We kept walking. A low branch of willow leaves was too long to block my way. I stepped aside. He stopped, took off his hat, and let the leaves drag across his bald head.

He bowed his head slightly, as if accepting some kind of blessing.

“Wen, feel the world, feel the nature,” he said.

He was not like Brooks Hatlen, the prison librarian played by James Whitmore, in The Shawshank Redemption (1994), broken by the system and institutionalized. He was earnestly learning how to exist in a world that had sprinted ahead without him.

He seemed almost happy. Maybe because the river, the night, and the freedom felt good to him. He played one of his favorite songs, “My Girl” by the Motown group The Temptations, music from his youth before he went to prison. It was a nice song, but I felt a little awkward; it was late, and the music felt too loud. But he did not seem to care. He swayed his shoulders and danced softly to the song by the river.

To my surprise, some young people walking by recognized the song. They joined in, singing and dancing along. An old man who spent half his life in prison, and strangers who were not even born when he went in, singing the same love song in the dark.

For a moment, reality stepped aside, fifty lost years returned through a melody, a branch of leaves, a bit of river wind. He was back in the world. Parole. Second time. Again.

He told me that the reason he came to this training was to talk to young people, to warn them not to pick up a gun, not to act out of anger the way he once did.

What he wanted to do was meaningful, I truly believed that. But there was another truth I could not ignore: the person he killed will never have a second chance. Their absence is permanent. No amount of wisdom or regret can return a life.

And I know he is trying to become someone gentle; someone careful. He pays attention to small kindnesses. He engaged in the training session to educate young people about avoiding bad behavior that might put them behind bars. He is not asking to be forgiven. He just lives.

These truths do not cancel each other out. They sit side by side, impossible to merge.

I am not the one giving him a second chance. That was the system, a decision made far outside my reach. I only happened to see one tiny corner of his effort to live with the world again.

Because I saw it, I am left with complicated feelings. Maybe guilt. Maybe confusion. My guilt is not personal. I do not know the victim. I feel guilty because I do not know where empathy is supposed to go in a story like this.

I cannot forgive him. I cannot condemn him either. My question is more private: What does it do to a person like me to stand in front of someone who has been given a chance that can never be given to the one who does not have a second chance? How do I hold my empathy without feeling that it leaks to the wrong side? How do I look at his effort to change without feeling that I am turning my back on a life that can no longer speak?

As a person, I believe in second chances. But a second chance is asymmetric. It does not return what was lost. I still do not know what to do with the fact that he is living and someone else is not. All I know is that a second chance is not a clean slate. It is a life built on uneven ground that change does not erase what came before it.

If he never changed, then a second chance would not be worth giving. But if he has changed, then a second chance still is not a clean gift. It asks him to carry a lot of weight.

If the world hands someone a second chance, then we also have to face the truth that nothing about a second chance is fair. Nothing about it evens the scales. But it is real, and it is what the world gives us instead of symmetry.

At the end of the week-long training, I asked him what he planned to do next. He said he would stay in Milwaukee. “Just learn how to live and help young people stay away from the gun.”

Standing by the river, I watched him let the willow leaves brush his head like a blessing.