How Three Gerhard Richter Canvases Speak to Our Moment

By Ben Fulton

October 11, 2024

Truckloads of paintings and artworks attempt to depict or advocate political and historical events and eras.

The Romans constructed arches to commemorate military victories for the foundation and building of empire. Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851) rings a collective bell inside our national head every time we see it. Jacques-Louis David’s paintings glorified, and even propagandized, the French Revolution.

Eventually skeptical, even critical, takes on historical events entered the pantheon thanks to artists such as Diego Rivera, whose mural The Spanish Conquest of Mexico (1929-1934) dared portray Hernán Cortés’s brutality against indigenous peoples. Salvador Dalí and Pablo Picasso became household names, in part, based on their diverging and bracing visual interpretations on the horrors of the Spanish Civil War.

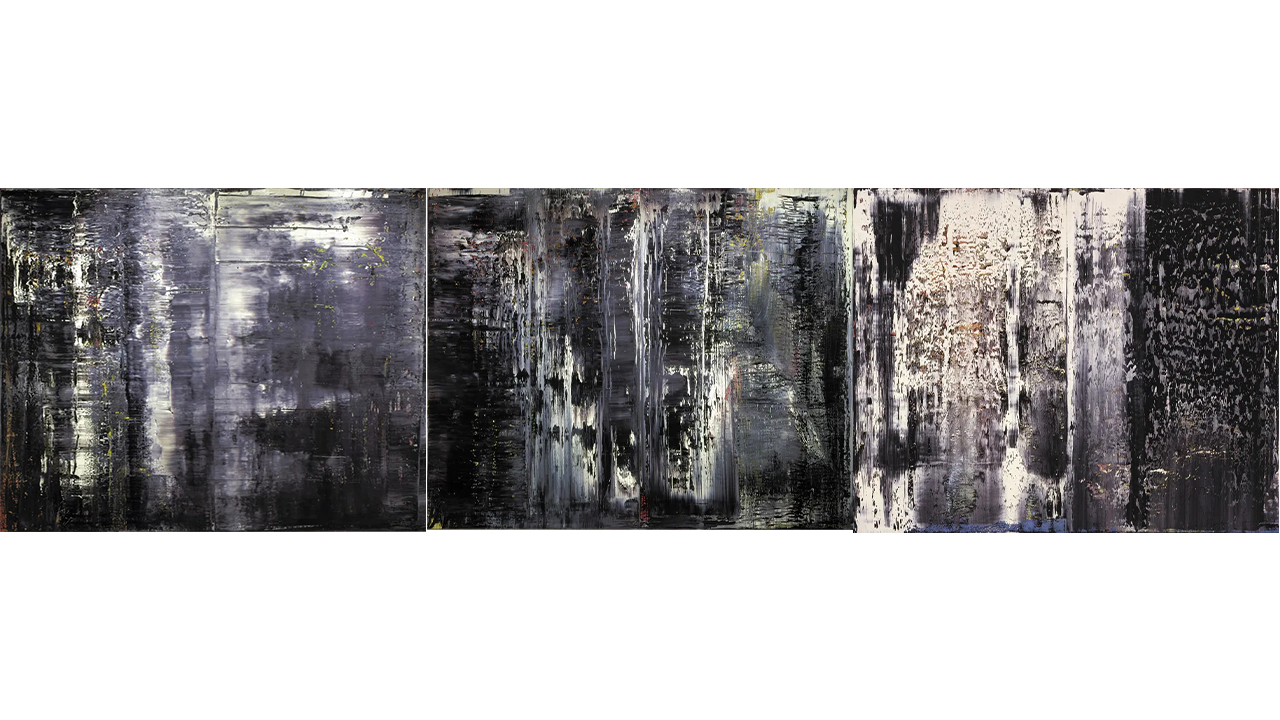

Politically and artistically, German painter Gerhard Richter’s trio of massive canvases November, December, and January (all dated 1989) are like nothing that preceded them.

Hanging in Gallery 251 of the Saint Louis Art Museum, they almost provoke the viewer into any attempt to decipher or make sense of them. If not for the museum label to the side, explaining that November 1989 was the month and year the Berlin Wall began to crumble and make way for the eventual unification of East and West Germany, viewers would never know these works carry any subtext at all, let alone a political one.

We are all familiar with the squeegee as a window cleaning tool. Richter made it a painterly tool, and one he has fashioned over years into a signature style. Attached to vertical or horizontal slides, and exacting intense pressure on paints, Richter uses the squeegee to distribute color in directions of his choosing, but not altogether under his precise control. The result is what art critics and historians like to call an “essentializing” effect that converges diverse elements into a unique whole. And if his many paintings can be called anything, they are unique by miles from most other painters. As a gentle contrarian, however, Richter likes to nudge most accepted assessments of his work aside. As documented in the book Gerhard Richter: Panorama (Tate Publishing, 2011), in a chapter by Achim Borchardt-Hume, Richter said he liked to think of November, December, and January as the result of what happens once the artist abandons ultimate control to instead allow the act of creation to determine ultimate outcomes. The only true decision an artist can make is deciding when a work can be declared finished:

Accept that I can plan nothing.

Any thoughts on my part about the ‘construction’ of a picture are false, and if the execution works, this is only because I partly destroy it, or because it works in spite of everything—by not detracting and by not looking the way I planned.

I often find this intolerable and even impossible to accept, because, as a thinking, planning human being, it humiliates me to find out that I am so powerless. It casts doubt on my competence and constructive ability.

A cynic would conclude Richter’s words fall on the side of chaos and pessimism, or that he is assuming a creative process more appropriate to jazz musicians and improvisatory music. A more charitable take is that Richter is a realist, and reluctant to let his paintings fall one way or the other. But to call Richter a “realist” in the artistic sense of the word betrays his paintings’ abstract nature. After gazing at these works many times over numerous visits, it is hard not to see them as murals of crux, change, and anxiety. Close examination reveals scant glimpses of color here and there. More often than not we associate color with the vibrancy of life. Suffocating that color, though, are massive horizontal and vertical strokes of dim gray and lambent white which, as Isaac Newton discovered, contains a spectrum of colors invisible to the human eye.

German artists who came of age and built their careers in the years after World War II felt almost duty-bound to reflect on their country’s shameful, odious twentieth-century history. Artists such as Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) and Anselm Kiefer, whose astringent work Fuel Rods (1984-87) hangs perpendicular to Richter’s canvases in the same museum gallery room, confronted that history directly, with radical and provocative statements designed to remind their fellow citizens of uncomfortable truths. Richter never took quite that route except, perhaps, in the quiet but discernable unease that these three works depict. In most other nations, division giving way to unity would be a cause for celebration. And in most of East and West Germany during late 1989, celebration was rampant. But so was anxiety about renewing geopolitical strength that, twice—through pre-meditated acts such as the Schlieffen Plan and Final Solution—terrorized the world with almost unparalleled suffering.

The most curious fact about these works is that they were exhibited months prior to the seismic events of November 1989 that presaged German unification. Curiouser still, though, is that after the fall of the Berlin Wall he chose not to retitle them. Creation precedes intention, but that Richter never changed their titles speaks to the same ambivalence he seemingly felt about German unification. In the end, these works speak to a looming sense of caution, restraint, and a cool head amid unbridled optimism. November, December, and January are a rare sight in art: works that seemingly depict and advocate a suspension of emotions and prognostications, rather than a celebration or rush toward them.

The act of voting, the act of making our individual voices heard in a civic forum, is a fraught analog to the act of artistic creation. Still, one individual choice in a sea of millions of additional choices can budge the needle toward some unforeseen tipping point. In choosing his artistic media—a squeegee, paints, and canvases—Richter makes his choices, but then leaves larger details to chance. The result of his efforts is art because the result of his efforts also reflects reality, which in the human realm is a blend of agency we control and the chance we do not.

As our country walks reluctantly toward another tense presidential election in which hopes ride as high as fears, and against which our national future will be written, Richter’s massive testament to the mystery of flux, the anxiety of change, and the necessity of choice against unknown fate is a vision we should all pause to consider. Most of all, it is one we should heed.