(EMI)

Nostalgia travels at the speed of sound. This is the obvious conclusion after watching four, five or—why the hell not?—twenty-five old MTV-era music videos archived in YouTube’s vast URL indices. The age of a person’s cultural tastes, on the other hand, travels far faster. So fast that if you search for a favorite song of your youth in video or live performance format you can span whole decades in the space of about five minutes.

I know, because this happened to me recently, when I showed my girlfriend the music video for the Pulp song “Help the Aged.” Not long after we watched it, the year of its 1998 release stamped its mark on my consciousness all over again: the months I struggled both to make rent and to save for a down payment on a house, the copious hours spent working at a then-struggling urban newsweekly, the courage I never found to ask out the ash blond woman who worked behind a certain coffee-shop service counter. Marching my thoughts back into the present, I counted back to the year of that song’s release.

“No way,” I thought. “Can it be that this song, one that furnished my soul for years, is now twenty-six years old?!” As Pulp singer/songwriter Jarvis Cocker himself croons in that very song, “Funny how it all falls away.” Time is not water down the drain. It is an ocean that evaporates faster the longer you keep your sights on the land-locked continent of adulthood. Looking back, you are shocked to find that you might have memories sufficient to recreate what has, physically, vanished.

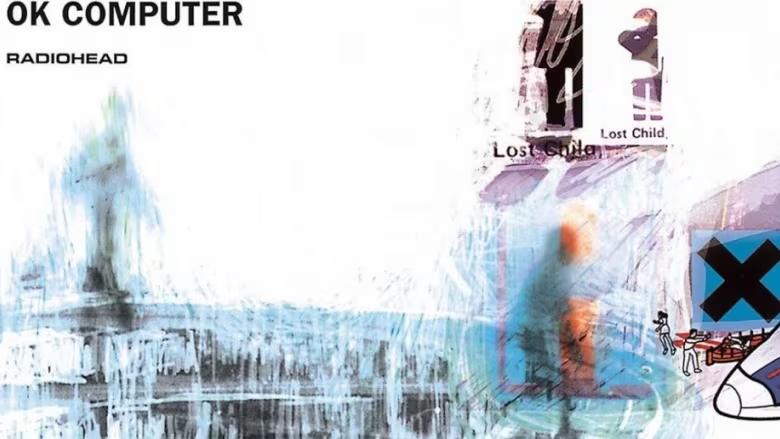

The shock of this revelation was a warm-up for what came next. Gracing my mailbox two weeks ago was a St. Louis Symphony Orchestra mailer promoting its upcoming February 24 performance of Steve Hackman’s Brahms X Radiohead, a “symphonic synthesis” of Radiohead’s 1997 album OK Computer and Johannes Brahms’ First Symphony, composed over almost twenty years, beginning in 1855, and first performed in 1876.

The combination of these two undisputed giants of music, albeit from different ends of the genre spectrum, was intriguing. Then it turned annoying. Here, again, was the nagging reminder that the music of my youth was old enough to suit a symphony hall crowd. Was it possible that many St. Louis Symphony Orchestra season-ticket holders were themselves old enough to recall the shivers of anticipation Radiohead’s album fired across the indie zeitgeist when it was first released? That question answers itself. Were it not possible, Hackman’s “symphonic synthesis” would not be on the program.

Brahms is probably the ideal composer to lead such an experiment. Beloved by renegade twelve-tone composer Arnold Schoenberg for his compositional innovations that simultaneously adhered to classical traditions, Brahms suits Radiohead’s similar manner of draping spiked melodic hooks over languorous tales of modern alienation. And it would be interesting, to say the least, to hear Hackman make Brahms and Radiohead hold hands, as it were. As with so many artistic genres, the influence of predecessors is unavoidable. I have no idea if Radiohead singer Thom Yorke or guitarist Johnny Greenwood, who went on to a renowned career scoring top-tier films, listened to or admired Brahms. Yet composers bridge influences every time they sit down to write their tunes. Why not fuse influences deliberately, as Hackman has? What could be wrong with making something new from elements that have previously proven their worth and status?

The problem with subjecting a song or album you hold dear to the whims of re-creation is that, if you are like me, they have long been cast and preserved in the amber of time and memory that make a work of music unique to the person who adores it. I say this as someone who was never a particular fan of Radiohead. OK Computer is doubtless a classic, and an impressive paean to both an era (the late 1990s) and an enduring mood (who has not been, or will not be, depressed by their commercial or political environment?). But the fact that a composer such as Hackman has folded Radiohead’s music into that of Brahms successfully enough to land in a performance hall is probably proof that time, alas, has at last caught up with Radiohead. It is not that Radiohead is no longer cool, but that Radiohead is now old enough to be respected. In the ruthless cycle of re-invention of pop music, and especially punk rock, that alone was enough to get you booed off the stage.

A singular aspect of rock—of all popular music, in fact—is that it is, in varying proportions, both timeless and of its time. The music of Elvis Presley may have eternal appeal, but the sound and cultural trappings of his style—i.e., his haircut, his dance style while performing—fence him inside a bygone era. Brahms, although he finished his first symphony not long after the U.S. Civil War, never had that problem. If he had, he would not be compatible with Radiohead.

“Fusions,” meanwhile, take place every time we listen to a song or album with new ears.

For certain members of my generation, the OK Computer of our time was the 1980 Joy Division album Closer. I first listened to this album while living with my father, fifteen years after my parents’ divorce. At the time, my home of Salt Lake City was drowned in an icy winter fog, making the album’s lyrics more intimate and its sound more tactile. Years after leaving my father’s house, I left the record untouched, fearing that it would never speak so well to me again. It was not until a trip to Rome years later, in a youth hostel bunk-bed in a neighborhood near the Coliseum, that I listened to the album’s first track, “Atrocity Exhibition,” again. Gradually, as I thought of all the brutality and death Rome’s Coliseum once hosted to crowds thirsty for spectacle, this incredible song came to vivid life. Time did not “fall away,” as Cocker sang. Rather, it stood still.