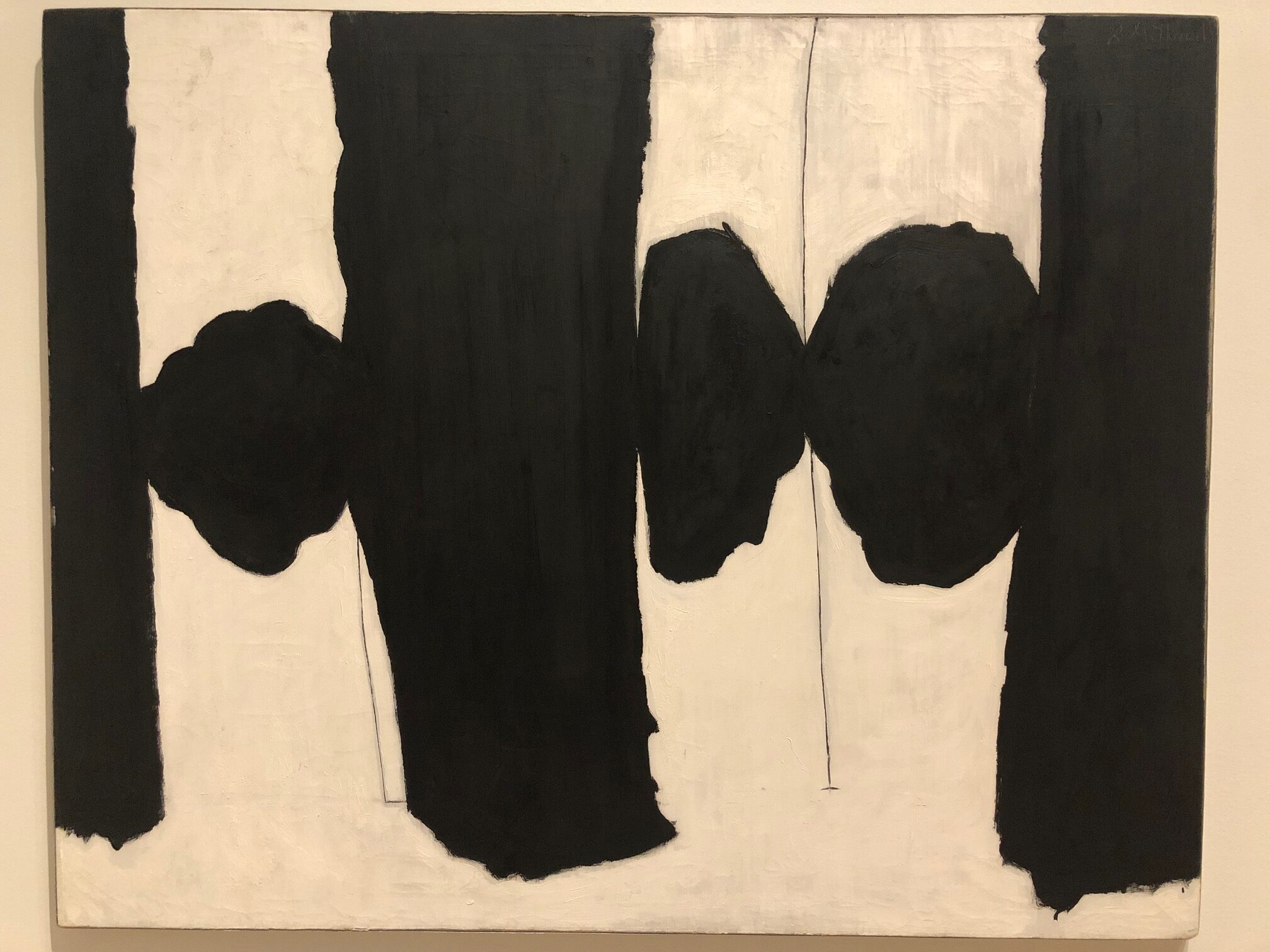

Robert Motherwell’s Catalonia (1951) oil on canvas, Saint Louis Art Museum (Photo by Ben Fulton)

Except for childhood asthma no doubt exacerbated by smoking as an adult and a series of rocky marriages, Robert Motherwell (1915-1991) led a mostly idyllic life. The child of a wealthy bank president, he grew up on California’s sunny Pacific Coast. He traveled Europe as a teen, then attended a string of Ivy League universities, Harvard included, where he studied more philosophy and literature than art. Rubbing shoulders with the celebrated, like-minded painters Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock, Motherwell enjoyed his time in the modern art spotlight as well, attending jet-set parties and dispensing statements on what made “modern art” modern. Basically, Motherwell was the brand of intellectual chin-strokers now derided by many as a “cosmopolitan elite.”

The problem with such pat descriptions of any one artist is that they tend to bend, transform, or even turn themselves inside out once you stand face-to-picture frame with their work. Such is the case with Catalonia, a 1951 painting that hangs in the Saint Louis Art Museum (Gallery 212S, to be exact) and is one of the earliest examples of Motherwell’s famous Elegies to the Spanish Republic.

The painting situates three black orbs between three ominous, almost threatening, black obelisk-like structures. Its absence of color lends the painting a starkness and immediacy that tells us something is under pressure, or about to experience imminent confrontation. Like all paintings it is a portrait of an image set and static. But there is an energy inherent in it that speaks to something still to be changed, or formed, all over again.

Motherwell’s work earns an attraction that is hard to articulate. When I last viewed Catalonia, I was shocked to have never noticed it before. I had the wonderful privilege of seeing just one other “Elegy,” Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic (1958) during a trip to Australia years ago, at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra.

Robert Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic (1958), oil on canvas, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra (Photo by Ben Fulton)

Viewers educated in European history will know beforehand that the painting’s name is overtly political. As the region of Spain with the longest traditions of political and cultural independence from the rest of the country, Catalonia was a stronghold of Republican sentiment during the Spanish Civil War during the years 1936-1939, with Barcelona a mainline of military communication with Valencia, also a Republican stronghold. The silos of historians’ ink used to document the events of this war chart differing causes and effects behind why it took place. Still, they can generally be said to agree on one distilling point: as a prelude to World War Two, the Spanish Civil War was a warning siren few wanted to hear, much less heed.

Pablo Picasso’s visual statement on this conflict is by now almost cliché, and if we are honest somewhat limited in scope because it confines its vision to one event, the indiscriminate bombing of civilians in Guernica by Spanish monarchists in league with German fascists. There is a credible argument that Salvador Dali captured the horror of civil war, or certainly its grotesqueness, far better than Picasso when he painted Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) (1936). Between these two works, Motherwell’s series of Elegies seem almost head-scratchingly passive. If not for their titles, we would be hard-pressed to believe they were representations of a tragic civil war.

But it is in Motherwell’s complete and utter lack of direct representation that we might find room to discover the heart of his Elegies. He assumes, graciously, that we also have the heart and intelligence to triangulate history, painted images, and varying titles on the theme of Spain’s self-inflicted suffering. Perhaps Motherwell frames the conflict in abstract terms because he understands that while his inspiration is specific to Spain’s history, conflict and strife are not specific but, from Homer’s Iliad to Ukraine and the war in Gaza, form a perpetual chain.

“The word elegy means a statement about the death of something that one really cares about,” Motherwell once said in a film for Christie’s auction house. “Somehow blackness was my destiny.”

Motherwell celebrated abstract art above all for its secular nature, as “the first art that does not work on tribal understanding.” If civil war is generated by any one force, it is tribalism. In Spain, it was driven by the biggest of tribal differences: religion, with Catholic monarchism against secular Republicanism, and politics, with landed aristocrats against reform-minded leftists.

His Elegies, then, are a testament to both what he hoped for but which quickly died when Franco prevailed, and what we fear when war breaks out. Perhaps the entities held tight between obelisk walls embody the forces of conflict yet unleashed, or the prisoners and combatants of future conflicts. Perhaps also they embody the impulses and energies of freedoms not yet won.