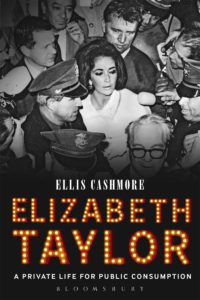

The cover of Ellis Cashmore’s Elizabeth Taylor: A Private Life for Public Consumption features Taylor at the center of a crowd flanked by police officers and journalists. Taylor’s fifth (and sixth) husband, Welsh actor Richard Burton, is positioned behind her and to her left (Taylor married Burton twice). The image, which features Taylor at its center but draws it power from the throngs of people surrounding her, is an apt one for Cashmore’s book. Not only does it indicate the book’s subject matter—Elizabeth Taylor’s life as a celebrity of unprecedented public prominence—it also suggests Cashmore’s approach to his topic. For although his focus is Taylor, his object of interest is much broader. In Elizabeth Taylor Cashmore argues that Taylor played a causal role in the creation of celebrity culture as it exists today. Its defining feature, he suggests, is the public’s unfettered access to the intimate details of the celebrity’s erstwhile private life. In arguing this, Cashmore does not merely situate Taylor within her historical context; he examines this context through the lens of Taylor’s public life, continuously relating this past to our present. Hence the appropriateness of the book’s cover: although he at times overstates Taylor’s influence, Elizabeth Taylor is, at its best, as much about the public lives of the many people surrounding Taylor as it is about Taylor herself.

Elizabeth Taylor is not a narrative biography; as such, key facets of Taylor’s life, such as her marriage to her first husband, hotel heir Conrad “Nicky” Hilton, and many of her roles in the 1950s are, at best, merely alluded to. (The book she authored at age 14, Nibbles and Me, about her pet chipmunk, garners more mentions than do the four films she appeared in in 1954, the busiest year in her acting career.) This is not an oversight on the part of the author. Cashmore has written a work that he hopes will appeal to both scholars and lay readers interested less in Taylor as an individual than in an interpretation of her as a 20th-century icon who profoundly influenced celebrity culture. He focuses, then, on those aspects of her life that played a causal role in transforming her from a “big star” to “news,” to paraphrase Taylor’s Giant co-star Rock Hudson. Long, seemingly tangential asides, such as his reverential discussion of Princess Diana as a late 20th-century celebrity martyr, make more sense when we remember that, although Cashmore is focused on Taylor, his real interest is in exploring how private persons became public commodities, in large part, he argues, because of the precedent Taylor established. Cashmore suggests that Diana was the first casualty of the transformation of celebrity culture that Taylor brought about. He describes how, in the immediate wake of the car crash that killed Diana in 1997, the paparazzi following her and from whom her driver had fled were faced with a choice: help the accident victims or secure priceless footage of the wreck. As Cashmore solemnly notes, “The paparazzi took their shots.”

Long, seemingly tangential asides, such as his reverential discussion of Princess Diana as a late 20th-century celebrity martyr, make more sense when we remember that, although Cashmore is focused on Taylor, his real interest is in exploring how private persons became public commodities, in large part, he argues, because of the precedent Taylor established.

For Cashmore, the Elizabeth Taylor we came to know—that is, the Taylor who courted notoriety and for whom there was seemingly no separating private from public life—emerged in 1958. This was shortly after she confided in friend and Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper that she was indeed having an affair with crooner Eddie Fisher, who was then married to ingénue actress Debbie Reynolds. As she famously stated to Hopper, using a turn of phrase that riffed on a line of dialogue from her film in theaters at the time, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof “Mike’s dead and I’m alive. What do you expect me to do, sleep alone?” Taylor’s third husband, film producer Mike Todd, had recently died in a plane crash. His close friend Fisher had served as best man at Taylor and Todd’s wedding. The affair transformed Taylor’s star persona, and, in the process, celebrity culture globally. Had news of the affair broken a decade earlier, Cashmore suggests, Taylor’s career would surely have been ruined. Yet as the 1950s gave way to the 1960s, social attitudes towards both female sexuality and Hollywood celebrity were changing, abetted by everything from the release of the Kinsey Reports (Sexual Behavior of the Human Male in 1948 and Sexual Behavior of the Human Female in 1953) to the premiere publication of the Hollywood tabloid Confidential magazine in 1952. Although Taylor incurred the wrath of many, others relished her exploits. For Cashmore, the Taylor/Fisher scandal was a watershed moment in the history of celebrity culture. From then on, the public felt entitled to both know and pass judgment on the intimate details of Hollywood celebrities’ personal affairs. In the process, the celebrities themselves became public commodities, the cultural significance of their private lives often outstripping that of their performances on screen.

Taylor’s affair with Fisher—or, more specifically, the dissemination and reception of news of the affair among the public—is one of two events identified by Cashmore as having profound significance for the future of celebrity culture. The other key event in Cashmore’s narrative is when Italian paparazzo Marcello Geppetti furtively photographed Taylor and Burton kissing on a yacht moored to the coast of Italy. At the time, Burton was still married to his long-suffering wife Sybil; she had endured his affairs before and assumed the relationship with Taylor would, like the others, flame out. Both Burton and Taylor had emphatically denied rumors that they were romantically linked. Reflecting on the incident, Cashmore writes, “His [Geppetti’s] photograph was not just of union, an illicit kiss of two star-crossed people. It was not just one of his trademark stolen moments. It was a message: the private life is over.” At the time of their tryst, Taylor and Burton were in the midst of filming battle scenes in Ischia for the 1963 film Cleopatra, an Island in the Bay of Naples. Cashmore notes that Italian journalists and news photographers were far less reverential towards celebrities than were their American counterparts. What Cashmore implies in his discussion of Geppetti’s photograph is that its publication and the ensuing scandal internationalized the methods of Geppetti’s particular breed of Italian journalist, making paparazzi a feature of global celebrity culture.

Cashmore’s discussion of Geppetti’s photograph is a good example of how he often uses Taylor as prism through which to analyze her life and times. The incident is not significant because of anything Taylor actually did (though Taylor was by no means a passive party to her own media exploitation). What matters for Cashmore is that the public’s desire to gain access to the intimate details of Taylor’s private life facilitated a qualitative change in the terms of the relationship between public figures and the public at large.

Cashmore’s prose unfurls as a pleasurably meandering series of reflections on both Taylor and celebrity culture punctuated by—sometimes unnecessary—definitions of terms (including “audiences” and “fascinate”), as well as in-text citations. He claims at the book’s outset that the citations are intended to advance the cause of research, allowing the reader to easily engage with and verify sources. However, Cashmore’s introduction of them brings the flow of his prose to a jarring halt. Similarly, throughout the book, Cashmore makes recourse to decidedly present-day references and analogies. For example, he notes that between 23 and 32 million Americans read Hedda Hopper’s syndicated column at a time when the U.S. population was 160 million. “This is the equivalent of a Twitter following of about 40–50 million, somewhere between Katy Perry and Taylor Swift,” he observes. I suspect there is a methodological rationale behind Cashmore’s use of these present-day references. Throughout Elizabeth Taylor, Cashmore probes the past with an eye towards the present, seeking to understand the origins of contemporary mass and celebrity culture. By citing stars like Perry and social media platforms like Twitter, Cashmore makes the relevancy of past to present explicit. However, the reader may find him- or herself puzzled by Cashmore’s inclusion of these seemingly out of place allusions to aspects of current mass culture.

In his concluding chapter, “Nobody Can Hurt Her,” Cashmore reflects on Taylor’s legacy for feminist politics. He cites critic Camille Paglia’s gushing appraisal of Taylor as a “pre-feminist,” that is, a women who embodies an unapologetic, defiant femininity possessed of “a sexual power that feminism cannot explain…the femme fatale,” Paglia continues, “expresses woman’s ancient and eternal control of the sexual realm.” [1] Cashmore smartly refrains from endorsing Paglia’s essentialist claims about the eternal nature of female sexuality; however, in appealing to her work, he undermines his effort to identify Taylor as a trailblazer for women’s sexual politics. Cashmore correctly challenges the idea that Taylor’s “code-breaking”—that is, her defiance of social and sexual norms—can be understood in relation to the advent of second wave feminism. As he astutely observes, throughout her life, Taylor sought to legitimize her romantic relationships within the decidedly normative institution of marriage. It is difficult to construe her repeated trips to the altar as a feminist assault on patriarchy. Cashmore thus turns to Paglia to argue that, perhaps, Taylor was a “pre-feminist,” albeit a curiously prescient one, one that post-feminist scholars like Paglia have since embraced as icons of empowered, sexually agential female identity. But how, then, can we construe her as path breaking? Certainly the femme fatale celebrated by Paglia existed in the public imagination prior to Taylor. If, as Cashmore writes, she can be understood equally well as either a “feminist hero, or a patriarchal patsy,” what could her possible significance be for altering the course of gender politics? Ultimately, Cashmore is inconclusive. “She did something for women,” he writes, but he is unsure of what.

As he astutely observes, throughout her life, Taylor sought to legitimize her romantic relationships within the decidedly normative institution of marriage. It is difficult to construe her repeated trips to the altar as a feminist assault on patriarchy.

As I have already noted, Cashmore is at his best when he uses Taylor as a lens through which to read changes in 2oth century celebrity culture. Yet he also argues that Taylor was herself instrumental in affecting the changes he discusses. He acknowledges that other women contributed to the transformation of mass culture as well. Yet he insists that, along with Marylyn Monroe, Jackie Onassis, Princess Diana, and Madonna, Taylor changed the rules of the game. This leads Cashmore to make a number of questionable claims regarding Taylor’s progenitor status. He suggests that Taylor was the first celebrity to court notoriety, the first to brand her persona by wholly identifying it with a line of perfumes, and the first Hollywood actor to publicly and without a sense of shame enter rehab for substance abuse. In instances (including some of the aforementioned) when Taylor transparently was not the first, Cashmore argues that Taylor did something qualitatively different than her predecessors. For example, discussing her perfume line, he admits that Sophia Loren’s eponymous scent Sophia predates Taylor’s first perfume, Passion. However, he argues that, unlike Loren, who merely “allow[ed] the cosmetics company [Coty] to produce a fragrance called Sophia, which she promoted,” Taylor was intimately involved with every detail of the launch of Passion, which capitalized on her identity-as-brand in a way that Sophia did not.

Yet in writing cultural history, identifying “firsts” is a perilous undertaking. In his effort to bolster Taylor’s significance for celebrity culture today, Cashmore, I would suggest, at times underestimates the degree of continuity between celebrity culture before Taylor and celebrity culture after her. In probing the relationship between Taylor and her times, he sometimes attributes excessive significance to Taylor. Cashmore is on his surest footing when he refrains from attributing historical causality to Taylor herself or events in her life and instead acknowledges that Taylor was only part of a constellation of factors that facilitated the rise of today’s celebrity culture. He overstates Taylor’s influence when, in his concluding chapter, he hypothesizes what might have happened had Taylor left Hollywood in the 1950s for a life of tranquil domesticity with her second husband: “In this parallel reality, Hollywood actors would have remained, well, actors: not all-purpose celebrities.”

Cashmore is on his surest footing when he refrains from attributing historical causality to Taylor herself or events in her life and instead acknowledges that Taylor was only part of a constellation of factors that facilitated the rise of today’s celebrity culture.

Would actors have preserved private lives had Taylor left Hollywood in the 1950s? Cashmore anticipates the reader’s resistance to his claim. In making his case, he rhetorically asks: Would there have been a Pax Romana had Julius Caesar not crossed the Rubicon? The comparison is somewhat apt given Taylor’s most famous role as Cleopatra; however, the historical implications of the actions of a military general of antiquity and a modern Hollywood star are difficult to compare. Yet Cashmere’s larger point is this: history may indeed be the product of a constellation of social and cultural factors. Nevertheless, individuals also shape history. Indeed, although they are influenced by the world around them, they also help determine and give shape to that world.

Yet in attributing primary influence to Taylor, Cashmore sometimes underestimates the myriad other forces—and other people—that have shaped our social, political, and popular cultural present. For example, discussing Taylor’s undeniably groundbreaking work as an AIDS activist, Cashmore asks, “Would Aids [sic] have received the support it needed without Taylor? Eventually, perhaps.” However, he proceeds to argue that the stigma of AIDS, regarded as a “gay plague” in the 1980s, may have prevented this. I do not wish to diminish Taylor’s contribution to AIDS activism; however, I would suggest that, here as elsewhere, Cashmore would do well to avoid such hypotheticals. His suggestion that, without Taylor, the AIDS crisis may not have been ameliorated risks diminishing the work of the comparatively anonymous activists who fought against fear and reaction to bring the AIDS crisis to the forefront of global consciousness. Taylor played a key role in AIDS activism, but this work was part of a collective struggle rather than an individual initiative.

Elizabeth Taylor: A Private Life for Public Consumption provides a compelling, copiously detailed account of Taylor’s life and times. Cashmore laudably focuses not only on Taylor during her heyday at Metro-Goldwin-Mayer, but also on her life after Hollywood, demonstrating that her influence on popular culture hardly ebbed as she aged. And, despite Cashmore’s scholarly attentiveness to Taylor’s historical influence, his work nevertheless allows the reader to indulge in the pleasures of biography, as Cashmore reveals many minute, intimate details of Taylor’s life. Of course, as Elizabeth Taylor demonstrates, Taylor was no stranger to having her private life divulged to a curious public.