Nobody looks up when a plane passes overhead, and most with window seats on an airliner pull down the shade. In 1942 Elias Canetti asserted that the “dream” of flight had “lost its soul” and been “realized to death.” 1 Well, that was after the bombing of Guernica and Shanghai and the London Blitz. Already in 1927, the year of Lindbergh’s solo Atlantic crossing, the narrator of Yury Olesha’s short Russian masterpiece, Envy, lamented the de-romanticization of flight: “From earliest childhood the name Lilienthal—transparent and fluttering as the anterior wings of an insect—has had, to my ear, a miraculous sound. This name is linked in my memory with the beginnings of aviation and seems itself capable of flight, as though it were stretched over light bamboo struts. Otto Lilienthal, that soaring man, was killed. […] A flying machine now looks like a ponderous fish. How quickly aviation turned into an industry!”2

My first flight was in a red, open-cockpit Waco biplane, built just a few years before Canetti’s pronouncement. For the short, three-dollar-a-head air-show ride, I was sandwiched between my father and brother in the front hole of this antique, which had been looping and rolling and trailing smoke in a Snoopy and the Red Baron gag a short while earlier. Wacos had been built nearby, and now—1967, give or take a year—there were still a good number of them in the area; in hopping rides they were staging a costume reenactment of the barnstorming 1920s—post-Lilienthal, to be sure, but very much aviation’s romantic past for us. Today, Jeff Bezos, Richard Branson and Elon Musk are blasting folks with the world’s fattest wallets into space, not so as to rekindle dreams of flight, but instead, to gin up post-apocalyptic survivalist fantasies of migration to other worlds after we have done this one in.

That is a fantasy with no purchase on me. Tomorrow I will drive thirty miles to pull out of a pole-barn hangar with peeling sheet metal siding a seventy-year-old, tube-and-fabric realization of my deeply embedded, retro dream, because for me and for the folks I most enjoy drinking a beer with, the soul is still to be found in flight and the machines that do it. Back in the day my faded yellow, four-seat 1950 Piper Pacer—a descendent of aviation’s Model T, the Piper Cub, but with wings shortened for cheaper manufacturing and twice the engine for hauling as many as four cramped adults—did take its renowned first owner, long-distance flyer Max Conrad, across the northern Atlantic four times. Now it drips oil like the beater Ford Falcon I drove at age sixteen (though it lacks rust holes in the floorboards and cigar-ash burns spotting the front seat), and its sheenless fabric is growing thin here and there. Still, a year ago September, with the rear bench seat removed, it took me camping in the Ozarks, over the Sandia Mountains and Albuquerque, and on to Zuni in westernmost New Mexico: my best bid at reaching other worlds. For years now my family and friends have deflected offers to go aloft in the Pacer—they do not have the time, or so they say—but if I do not get up every week or so I get moody and short. Four winters ago, during a particularly frigid flight east to Pittsburgh, ice blocked the engine’s breather tube, pressurizing the crankcase, blowing all my oil out past the prop seal, wrecking the Lycoming and marooning me in north central Ohio after an emergency landing. A year later, when all was said and done, I had spent as much as the whole plane was worth for an overhaul; so I have bought that airplane twice. Why? How did my life arrive at this summit of irrationality?

Today, Jeff Bezos, Richard Branson and Elon Musk are blasting folks with the world’s fattest wallets into space, not so as to rekindle dreams of flight, but instead, to gin up post-apocalyptic survivalist fantasies of migration to other worlds after we have done this one in.

Back in the early 1990s I was a tenure-track assistant professor at the institution that hosts this journal and finally—just barely, with a salary in the mid-twenties—possessed the wherewithal to pay for lessons. My psychologist brother had gifted me an introductory lesson, and soon, on days without classes, I started sneaking west on Highway 40/61 to the Spirit of St. Louis airport; not, however, without enjoining my instructor to never tell anyone that he was teaching a young Wash. U. faculty member—nobody must know of these hours diverted from research and course preparation. It turned out that he was also teaching another assistant professor on the tenure track, from a department in the building adjacent to mine, who had likewise demanded secrecy. We had both seen deserving colleagues sent packing, and this was back in a strange, transitional era, when, for instance, young women of my generation were being hired to tenure-stream positions like never before, but they were also warned by their chairs against starting families until after gaining tenure.

When I did come out, so to speak, to my colleagues, I composed a ready answer for that “Why?”: I fly because (a pause here) it’s safer than sex and (pause) cheaper than psychoanalysis. That was a better line back during the HIV/AIDS terror, and when I myself was immersed in Freud and Lacan but evading the couch.

Of course, there has long been an understanding of flight as taking the place of sex; Wilbur Wright claimed that he did not “have time for both a wife and an airplane.”3 What I really regret is never hazarding to bring flying up with a most admired colleague in a neighboring department, the poet Howard Nemerov, who had flown Spitfires in the Battle of Britain; he died before I found the hubris to suggest we might share something beyond the ruttish smell of the gingko trees, which pervaded the route between our buildings and the library, and about which he would offer pleasantries if you encountered him there. Now emeritus (of another institution), with years of administrative work behind me, too, and having just published what will likely be my last scholarly book, the truth is I would rather talk about airplanes than my professional field and am prouder of my commercial and instructor ratings and difficult flights than the handful of scholarly books bearing my name, that is, the name of my father.

Speaking of which: if I had answered that question “why?” honestly, I would have said that it all must go back to him. Three-fourths of the pilots whom you ask why they fly will, in one way or another, come up with that answer.

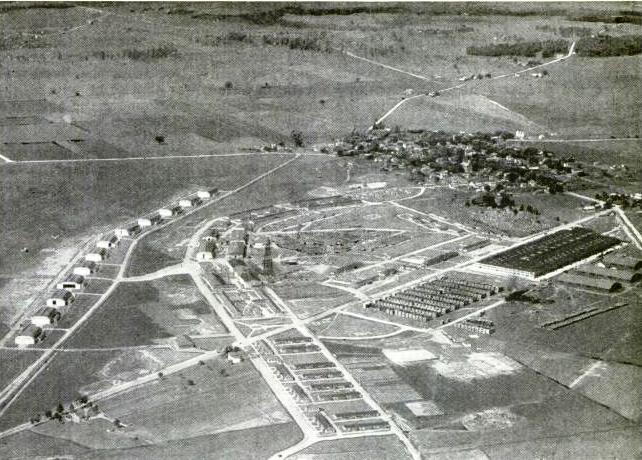

Aerial photograph of Wilbur Wright Field, now Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Fairborn, Ohio, circa 1920. (Popular Mechanics Magazine)

Some of my oldest memories: a bedroom ceiling from which hung some twenty-five or thirty plastic models, assembled at the dining room table by my father (while I watched and learned a little something about the distinctive odor, if not the intoxication, of glue-sniffing); giving them away to friends on the street when the family furniture store went bankrupt and we moved from Fairborn, a town bordering Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (for some reason my mother declared that they could not go with us); watching the annual air show at Wright-Pat from the rooftop of our one-story hilltop home; wondrous dreams of taking flight with arms as wings from the jungle gym in the backyard, from which I had once fallen and knocked myself out; the fantasy that my father, a desk-jockey Air Force reservist who had flown privately until I came along, just when the business began failing, would be called up and asked to fly some sort of fighter jet with a child’s seat in the back.

“Could you ever be assigned to fly a fighter jet?”

“No.”

“Well, if there were a big war and they ran out of pilots, what then?”

“Well, maybe…”

There were also repeated dreams of one of the massive B-52s based at Wright-Pat crashing into our house. A Fairborn girl with whom I once shared a ride back to Ohio from college confessed to the very same nightmare, with the bomber striking her house and skidding through her bedroom door toward her double bed. The memory of these dreams may have been belatedly shaped by a miraculously nonfatal B-52 crash on approach to landing that had occurred just a few years ago, in a field east of where we used to live; more likely, our common nightmare recalled the worse incident, fifteen years earlier, in which an F-104 Starfighter from which the pilot had ejected plummeted into a house in nearby Beavercreek, killing two children, one a toddler my age. I do not remember either of these accidents, but I remember the dreams.

My father’s boyhood scrapbooks of WW II aircraft are boxed in the basement, as are three decades of Flying magazine, beginning from the late 1940s; having leafed through each issue, I can claim to have been reading Flying since before I was born. His own flying had ended with my birth and the sharp decline of his father’s business: his maroon Stinson Voyager, an airplane of the same vintage and similar in design to the one I would buy fifty years later, had to be sold. (So were a couple of chairs from our dining room set, and when the store got locked up by the sheriff, our lawn mower happened to be located there and ended up sold, too, about which my mother griped for decades.) Every rare once in a while he would sneak in a short lesson at some nearby strip. I know this because he took me along once, and I sat on a vinyl cushion in the baggage compartment of a two-place Piper Colt trainer, unable to see out the window, while he did a few take-offs and landings. It cost ten dollars, and I was not to tell my mother. I always figured it was the expenditure that worried him, but it may have been the fact of having taken me up without her permission. My childhood involved many weekends with one day spent parked by a local airport, listening to the tower frequency, learning to identify makes and models, and collectively fantasizing about the day Dad would buy a Cherokee Six, big enough for the whole family to travel in; and another day trailing Mom as she wasted a realtor’s time seeing houses for sale that we would never be able to touch, preferably with swimming pools.

“So, I hear you’re a flyer,” my grandmother greeted me on my last visit to her nursing home.

St. Louis had a wonderful aviation culture. Fine general aviation airports in any direction from which you exited the city, and over the years I bought into a series of partnerships that had me flying out of several. Three of them closed during the years I was there, though: Arrowhead, St. Charles Muni, and Weiss, where the first plane I co-owned was based. Before 9/11 you could fly over Busch Stadium during a baseball game low enough to grasp uniform colors and the players’ movements, and a few circuits around the Arch was always a hit with visitors. I remember returning from a long flight out west just as the sun was setting, with shadows putting hilly terrain to the north in high relief, flying past the reddened bluffs mirrored in the Mississippi by Grafton and Elsah and on toward Alton Regional, and thinking that this was a sight as beautiful as any I had seen over desert and mountains. Circling the city you might join up with bald eagles by the Winfield dam. And every Sunday the owner of Creve Coeur Airport rang the bell at noon for an inexpensive barbecue lunch, which he prepared, and all the TWA captains and McDonnell-Douglas engineers based there had their hangar doors open, exhibiting one of the finest collections of antique, classic and homebuilt airplanes in the United States.

A few years before moving away I became partners in a later model of just such an aircraft as my father had dreamt of acquiring. It was a six-seat Cherokee, but better, faster, with retractable gear and the latest avionics. When I took him for a ride and turned over the controls for a few tentative turns, he frowned and said, “I don’t like it.” And so I radioed Spirit tower and we headed back to land. By then all the relics of his own brief flying career had been destroyed in the aftermath of a nasty second divorce; otherwise I would have his logbook, old charts, and flight computer (a kind of slide rule) boxed in the basement, with his magazines and his ashes.

St. Louis had a wonderful aviation culture. Fine general aviation airports in any direction from which you exited the city, and over the years I bought into a series of partnerships that had me flying out of several.

A year after I moved away from St. Louis, one of the partners in that Cherokee filled it with fathers and sons and flew down to a trout-fishing resort in Arkansas; on the take-off for home, overloaded on a hot summer day, he crashed it into a hillside.

The Oedipal dimension of flight’s unconscious meaning features centrally in Douglas Bond’s The Love and Fear of Flying, a fascinating post-WW II psychoanalytically oriented psychiatric study by a former flight surgeon of “emotional casualties” and “flight neuroses”—today’s anxiety disorders, panic attacks, and PTSD—among bomber pilots and crewmembers of the Eighth Air Force flying out of Great Britain. Bond also follows other sometimes related interpretive vectors as well, however, reading the airplane as a narcissistic self-object, as well as a feminized substitute for an erotic object of incestuous desire; reading flight as a challenge to and attempted mastery of death, an invitation to dreaded punishment and an “unbridled” exhibitionistic flaunting of it. Although the term never appears, the psychoanalytic reading of the fetish might have served well to tie it all together.

Remember the famous sonnet by the British fighter pilot James Magee, which Ronald Reagan cited at the end of his televised address to the nation when space shuttle Challenger blew up shortly after launch?

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

[…]

Where never lark, or even eagle flew—

And, while with silent, lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand and touched the face of God.

You hear that poem often when a flyer dies, and it is meant to suggest a profoundly spiritual dimension to the activity of flight in a life that, though prematurely ended, achieved something meaningful. In writing (here of fighter pilots) just after the war, Dr. Bond finds, instead, male aggressivity unleashed by mortal combat: “Every dangerous success is an indulgence of incestuous desires, at the same time as it defies and mocks the authority and power of the father and thereby brings reassurance of omnipotence and of the ability to withstand castration. Pilot Magee’s poem shows the exultation he felt when he dared to ‘touch the face of God’ and ‘got by’ with it.”4 The B-29 that delivered “Little Boy” over Hiroshima, “Enola Gay,” was named after pilot Paul Tibbets’s mother; think a bit about that one. In sum, one flies to be like the father; one flies in defiance of the father and the castrating punishment that is his to mete out; the airplane is a phallic symbol; the airplane stands for the female erotic object. And so on.

You can find the same themes, though not in the Freudian idiom, in some of the finest writing about flying of recent decades, by Laurence Gonzales. One Zero Charlie: Adventures in Grass Roots Aviation (1992) explores the culture, and his place in it, at a small, privately owned but public airstrip in the Chicago suburbs, Galt Field. In The Hero’s Apprentice (1994) he writes about people who do dangerous things, either as their profession or a hobby. The book of essays begins and closes with flying: aerobatics, flying off aircraft carriers, non-precision instrument approaches to minimum allowable altitudes through an icy cloud deck. And his two themes are the encounter with death and conquest of fear, on the one hand, and measuring up to the father, on the other. Gonzales’s father had been a B-17 pilot shot down over Germany during WW II. With one wing blown off by flak, the plane helicoptered down like a maple tree’s seed pod, and Gonzales’s father miraculously survived. This was part of the mythic aura surround his “cool” dad, who never talked about the crash, however, and did not continue to fly. Gonzales’s grandfather had been, if anything, more heroic: a fighter in the Mexican revolution, he then emigrated to the United States by foot and established his family there. Hence the book’s title: flying is his way of becoming a “hero’s apprentice” to his father and grandfather.5

But none of that explains much for me. If there was ever a time that my own father loomed as heroic, then that was long ago lost to infantile amnesia. His aviating stories were few: of failing to “plant” his Stinson while landing in a crosswind and suffering a groundloop (when a tailwheel airplane pivots around one of the mainwheels, doing a donut and dragging a wingtip, or worse, rather than tracking straight down the runway); of nearly putting it into the trees taking off at French Lick after flying down there to pick up his parents on a hot, humid summer day, when aircraft and engine performance were diminished. Talking airplanes was all about evoking a fulfilling past and an empty present, and longing: he wanted to, but couldn’t, for lack of a more commanding signifier of masculinity. This lack only loomed larger as I approached adolescence and beyond. In graduate school I was also working part-time restaurant and library jobs and mailing him checks so he could pay his meager child support and avoid jail.

The B-29 that delivered “Little Boy” over Hiroshima, “Enola Gay,” was named after pilot Paul Tibbets’s mother; think a bit about that one.

I did give aerobatics a try, in a Citabria (read the aircraft’s name backwards) based at St. Charles Smartt Field. This rental and training operation was a venture of two McDonnell-Douglas test pilots, one of whom was himself killed east of Alton, in 1996, looping an F/A-18 too low. I flew with the other guy. A few spins and barrel rolls went fine, but the first attempt at a loop provoked intense nausea, and there ended my flying as an extreme sport. A few years later, when a woman with whom I flew down to Memphis for a memorable date weekend tried to liven things up by provoking me to roll or loop our stolid Cessna, I explained what it meant for an aircraft to be certified for aerobatics, and the ease with which I, untrained, could exceed g limits and pull the wings off this one, which was not so certified.

“My brother would definitely be doing loops and rolls,” she retorted.

So, I did not measure up. This moment sticks in my mind as a hint that the transgressive, incestuous meaning of flight that Dr. Bond wrote of, following Freud, might have relevance beyond little boys.

Nor do I much challenge the weather. I can fly on instruments but stay well clear of icing conditions and will remain on the ground rather than put myself in a situation where I will have to fly an approach to minimums. I enjoy the view from aloft above all, so flying in the clouds does not appeal. There was the time I frightened my wife, who sat in the way back of the six-seater, our infant on her lap, while we weaved around storm cells on a flight back to Spirit from western Massachusetts. Listening to other traffic (mostly airliners far above us) request deviations, and Air Traffic Control obligingly vector everybody around the weather, and able myself to see the storms in real-time on the Strikefinder instrument on our fine panel, I knew we were safe; within twenty to thirty minutes we would be past this front and in fine weather for the rest of the flight home. But she spotted an airport through the clouds below us and, panicking, insisted that we land “now.” So I canceled my instrument flight plan with ATC and put it down right there in western Pennsylvania, where—when the front we were picking our way through stalled out—we got stuck with very low ceilings for a couple of days. The pilot in command had been cowed by his passenger—not the stuff of heroism.

By the time I reached western Kentucky and into southern Missouri, flying low for the least adverse winds, skies had cleared, but it was beastly hot, and every five or ten miles a field was burning, so I was flying at the sun in haze. I barely made the unlit backcountry Ozark strip before dark.

Night flight also offers added risk, especially behind only one engine, though it does not demand special skills. Ten or so years ago I suffered an electrical failure on a dark winter night and, with the windscreen frosting up—was I panting?—had no way to turn on the runway lights of the rural Illinois grass strip where I then kept the Pacer; after three or four passes I landed smoothly, but I have not embarked after dark since. These days I do not see so well at night anyhow.

September’s flight to New Mexico was a test of sorts, I suppose. First of all, a test of my own aging frame’s flexibility and endurance: two full days in the cramped cabin seated on sagging springs left my back stiff and sore. Climbing in and out of the plane at fuel stops became a chore. I had never flown two long days in a row like that, and my last lengthy cross-country was fifteen years ago, in a faster and better-equipped machine. Getting out of the Pittsburgh area the ceiling was lower than forecast, making it a challenge to miss the powerplant stacks west of town while staying lower by a legal margin than the cloud bases. Visibility was poor, and my attitude indicator tumbled; that instrument would keep me upright if I blundered into the clouds, but I had a portable backup and flew on. Headwinds were fierce, so I deviated to the south where forecasts showed them lighter and I would get out of the weather sooner. By the time I reached western Kentucky and into southern Missouri, flying low for the least adverse winds, skies had cleared, but it was beastly hot, and every five or ten miles a field was burning, so I was flying at the sun in haze. I barely made the unlit backcountry Ozark strip before dark.

The next day I was taking this tailwheel airplane, tricky to land in crosswinds, through Oklahoma, Texas, and the width of New Mexico, where it really blows; and though I was lightly loaded, the high elevations and summer temperatures had me worried about takeoff performance, too. But then I passed Albuquerque, and the views became truly spectacular. A solitary, well-defined storm cell was crossing my path as I approached the southern slopes of Mt. Taylor; while skirting it to the left toward a lowering sun unblocked by the drizzle trailing the real rain, rainbows sprouted to augment the mesas, buttes, canyons, and scrub. I had never seen it so green here; yes, they told me, it had been very wet. There was hardly an elegant landing during the whole trip, a few real bouncers, but I got it down safely, without any go-arounds, and without bending metal. Hardly the flaunting of danger Gonzales writes of.

Putting the plane away after I got home, I thought how I would tell my father about it.

For thirty years I bicycled to work. And I was hit by vehicles three times (run down from behind on Forsyth once by a Wash. U. shuttle bus). I guess danger is where you find it.