It was a beautiful evening. We were high in the mountains on the Pacific Coast of California. A cooling breeze floating over the outdoor theater, and over the city of Saratoga beneath us. Music from the band soothed and caressed us. The full moon looked down approvingly and seemed to smile.

A brown woman in a white flowing gown appeared on stage and sang a song about love. She was from the Netherlands, she told us, and talked to us about why she loved “love.”

After a few minutes, there was a slight shifting of the lights, a rising rhythm from the band, and we became aware that Common had slipped out from one of the shadows.

Dressed in a red t-shirt and white short pants, he started dancing to the music, and freestyling.

I’m down for my people

I come around

I’m from Chi town.

As soon as he began to freestyle, the audience leaped to its feet.

I love my people—

Who come from the Bay Area

San Franciso, Oakland—

They know that I’m outspoken—

I love my people from Berkeley—

When he said “Berkeley” I had to smile and get involved. I am from “Berkeley.”

Common the rapper represents the contemporary verse of the oral poet. By rhyming on the name-places, he is pulling the members of the audience into his performance. Just as I was called in by his reference to “Berkeley” so were many who cheered, pulled in by his reference to the place in the Bay Area they came from. He referred to us collectively as “Saratoga!” Each epithet brought laughter and joyous outcries of pleasure.

After a few minutes, there was a slight shifting of the lights, a rising rhythm from the band, and we became aware that Common had slipped out from one of the shadows.

When he said, “Oakland,” he rhymed it with “outspoken” and nailed it on the beat. When he said, “Chi town,” that was like a ten-page outline of his biography. Just in that one phrase, he tells you about growing up a black man in Chicago.

“I didn’t know that hip-hop would take me on this journey,” he told us, in a form that is somewhere between singing and speaking, “I didn’t know that Hip-hop would take me to see the world in new ways. It would take me to Japan, to France, to the African continent. It would take me to Saratoga, California [applauses], and then it would take me to the White House to meet first the first black President, and Michelle Obama. Hip-hop would take me around the planet—who would know?”

“This music caused me to write my first rhyme,” he rapped, “This music was calling me. It gave me love!”

Love would never down me love would

A Love I had not known before

It was a love more against me

This music caused me to write my first rhyme.

‘Well let me tell you about a trip

I was the run coldblooded

Here to roc the party

Could you rock with me’

Dropping the rhythm, Common said, “I [wrote that when I] was twelve years old!”

This free-styling is a part of the oral tradition that takes us black people back to George Moses Horton, a slave poet. Born in 1797, Horton was a slave until 1865, when he was freed by the Union Army. He lived out the rest of his life in Philadelphia and died in 1893.

In the slave world of North Carolina, where black men or women were punished (sometimes with death) if they attempted to be literate, Horton was determined to be a poet. He devised a method to do this. After singing Wesleyan hymns in the church, he would repeat the rhythms when he chopped cotton. Over the chopping cotton rhythms, he would substitute the words of love.

At the end of the workday, Horton would recite the new composition to a white friend at the nearby plantation who wrote it out for him. One of his white friends liked his composition so much he gave him twenty-five cents. For the rest of his slave life, Horton never took less than twenty-five cents because of “Mr. Alston,” as he called his patron.

… Horton was determined to be a poet. He devised a method to do this. After singing Wesleyan hymns in the church, he would repeat the rhythms when he chopped cotton. Over the chopping cotton rhythms, he would substitute the words of love.

Just as Common attributes his talent to “this music,” Horton would attribute his talent to the “muses,” not literacy.

Love and improvisation become tools of the oral poet.

Into the show, he called a young lady from the audience to the stage.

“Will you come up and sing with me?” He asks a girl in the audience. “You don’t have to sing that good…”

Not surprisingly, the girl comes up on the stage. Common says something to her we cannot hear. She responds. Now, he turns and introduces her to us. Her name is Sonya from San Jose (big applauses from the San Jose).

Then he begins to freestyle on her name. First, he has to bring the audience in by calling the roll. How do you know if you are with true hip-hoppers? Read the name-brands.

“I look in the audience—! I see Hilfiger!”

The person with the Hilfiger grins.

But that’s about my daughter

The best way to understand Common is to remember Joyce’s stream of consciousness in Finnegan’s Wake. If you have not read Joyce, imagine you have. The double meanings are there because they are sonic, not logical. Words are explosive, associative. Don’t make sense, make sound!

Sometimes I think about my daughter

Put things in order

I came to get on you

Then, he turns to Sonya:

“Looking at this beautiful

Woman in dark dress named Sonya—

(Sonya has on a dark dress)

Sonya is extra fresh

He looks at her chest:

She has on some snakeskin

We break wind

(That was a bad line! but he cleaned it by repeating it.)

Common comes closer to Sonya.

“She told me she was speechless,” he tells us. Remember they talked briefly.

She didn’t want to say i

But looking at the style

I just might lay it [unclean]

I am down for my people

I come around

I’m from Chi town

I turned the page

This is the kind of thing I say

I come, I feel this

Come on down, Sonya

You should Come close!

We can drink some wine and toast

At the way you cuss me

I just want you to trust in me

I kind of laugh

I’m driving in the fast lane

I want to give you my last name.

He mocks a hug and a romantic kiss, and Sonya returns to her seat amidst an eruption of pure appreciative cheers from the audience.

As Common bids her farewell, he turns to the audience as if he were Hamlet, in a soliloquy, he says, “Saratoga!” He addressed the audience as one. “Saratoga, It’s a party! It gets crazy! Let’s give it up for Sonya, you was a great sport. There goes the love of my life! We broke up! She called me on the phone and said we’re done. I want to be with somebody else!”

Horton, the slave poet, also used love poetry as a fantasy to get his performances across. White students at the University of North Carolina requested love poems for their girlfriends from him. Horton would recite them; and in writing them down, the students pretended that they had composed them.

Horton soon was in great demand as a ghostwriter. It was a spring day in 1844 when William Bagley, twenty years old, recorded in his diary how he hired Horton to write a love poem for his girlfriend.

Just as Common had asked a few particulars about herself from Sonya, so did Horton ask Bagley about his girl, her name and where they were in the relationship, and other details.

In his diary to his sister, Clementia, he wrote that he was unable to write a love poem to a certain young lady, even though he had spent four hours with her and was deeply in love. He describes how he went across the campus from McCorkle Place, where he found the slave poet. At that time, Horton was forty-seven years old. It was the custom to give Horton the name of the girl, which Bagley did.

Just as Common had asked a few particulars about herself from Sonya, so did Horton ask Bagley about his girl, her name and where they were in the relationship, and other details.

After this interview, Horton was ready, and Bagley took out his quill. As the poet improvised an acrostic on Mary’s name, Bagley wrote it down, then paid the slave a generous fifty cents from his weekly allowance of a dollar.

Back in his room, Bagley wrote Mary a letter, in the middle of it inserting Horton’s poem:

Magnet of every tuneful bard!

Ador’d of lovers on their knee,

Resplendent girl, my true regard

Yet never has been told to thee.

Why should I hence forbear to sing?

Impell’d, I cannot love deny.

Let me ascend on pleasure’s song,

Let me display my love or die.

Imperial Nymph! I must be thine!

And still thy winning form adore,

My lips would pain pronounce thee mine,

So should I smile and frown no more.

No description survives of Mary Williams’ response, but we may guess that she smiled when she read the inserted poem, and perhaps laughed, impressed by Bagley’s talent, his mind learned in the classics, and by his sincere emotion. No one had ever called her an Imperial Nymph! Or spelled her name out in an acrostic! (In the end, however, Mary Williams never married Bagley. But she kept the poem.)

Scholar Timothy Williams summarized the relationship between the slave poet to the student client this way: “Unable to express his love himself, Mr. Bagley thus turned to a local slave … Students like William Bagley hide the authorship from the female recipients of Horton’s love poetry, thus claiming the literary labor of a slave as their own.” ¹

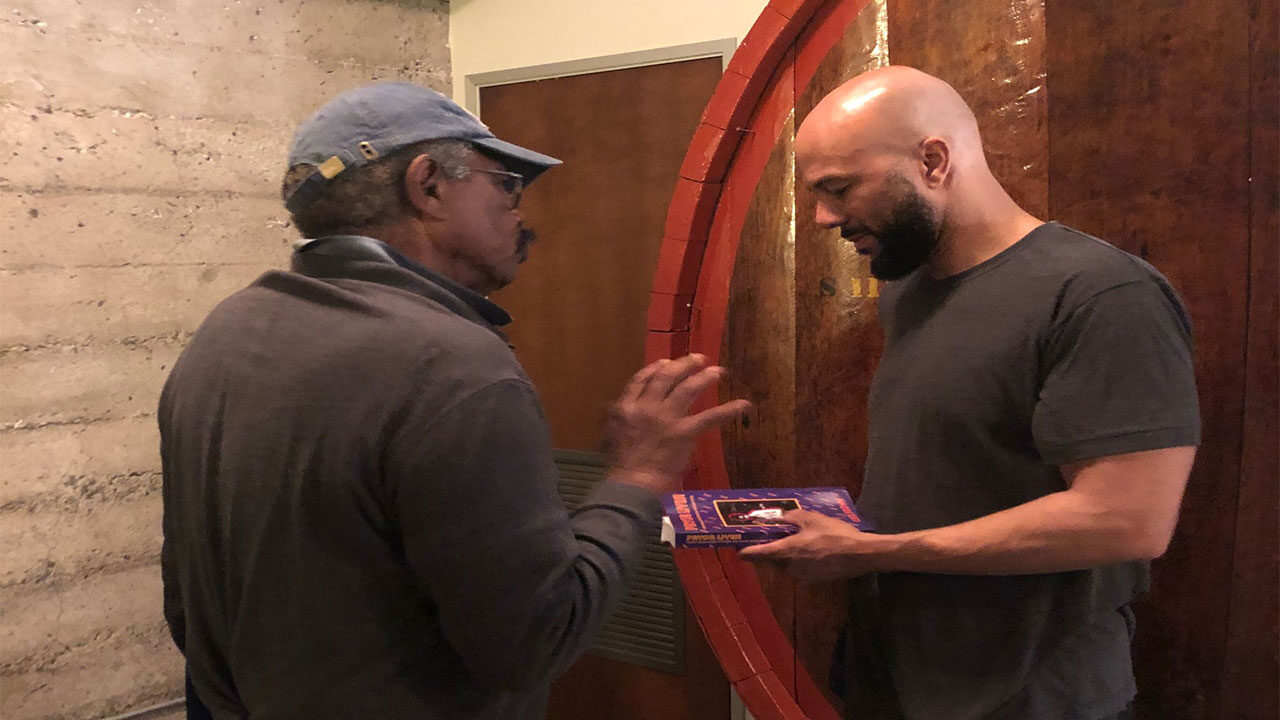

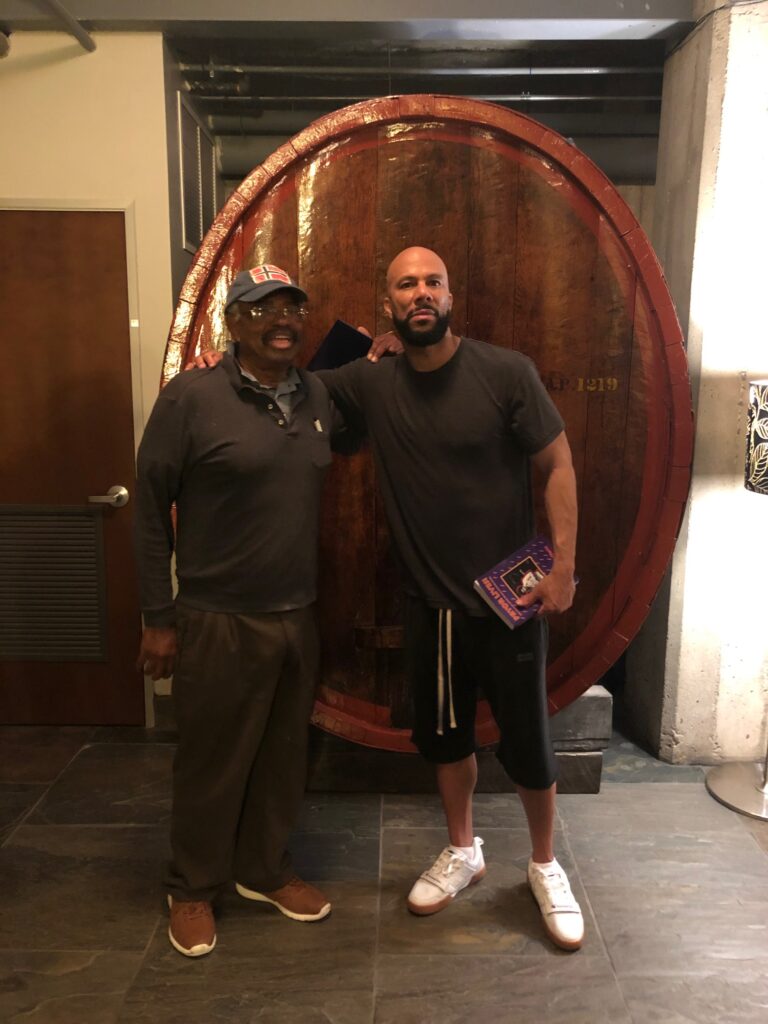

After the show, I met Common backstage. I told him the story about George Moses Horton. Although he had never heard of Horton, he was immediately impressed. I showed him a printed verse of Horton’s most famous poem, “Liberty and Slavery.”

“But this is not how he created it,” I explained, “How he recited it is closer to how you recited your poems.”

He was not dismissive, but eager to know more about Horton and the contribution he made to oral poetry. (Paul Lawerence Dunbar came next, then Langston Hughes, and then the Last Poets and now his generation.)

I agreed to send him some more information.

When Bagley paid for the poem, he also paid for the right to use it as his own creation. The “I” of the poem that Horton created was left open for Bagley to fill.

Through the poem, Bagley was recreated, self-fashioned. He developed a persona, an avatar. No longer was his persona just that of the slave-owner’s son who went to the university, studying Greek and Latin. Now through the oral poet Horton, Bagley was also a “poet,” a lover of poetry, and a lover of a woman, a certain Mary Williams. Through the ghost poem, Bagley was able to experience vicariously what it felt like to also be a poet, although he was not truly one himself.

And who was Horton? I suspect that he was someone like Common, who would dance and gesture when he composed. I can imagine that when he made the end rhymes, he made Mr. Bagley smile with admiration.

What oral poets do for us is that they make us want to be like them.

Perhaps Bagley thought that by copying down the poem as his own (and paying for it), he had captured some of the gesture, voice, and movement of the actual poet. The poem on the paper was a pale representation of Horton’s unique performance, but it was enough to inspire Bagley to imitate a real poet.

At the end of the Saratoga show, Common told his audience that he had records, t-shirts to sell. This is equivalent to Horton’s selling the transcript version of his oral performance.

What oral poets do for us is that they make us want to be like them. Like Bagley, we want to be that person who can express his love so beautifully, with such sincerity, and liquidation of the loss we feel when we are in the presence of someone we love. Bagley knew he was not a real poet, but it was nice to feel like one.