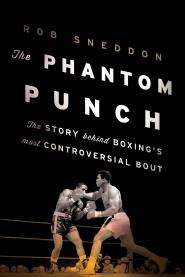

Boxing fans under the age of 60 might not be as familiar with the controversial subject of this book as those of us who lived through the tumultuous ’60s and watched the rise of Muhammad Ali. The “phantom” punch that laid out Sonny Liston on May 25, 1965, only 2 minutes and 15 seconds into the second Ali-Liston fight, seemed proof that the bout was just another “fix” in the legacy of dirty boxing. Spectators at ringside, one security guard in the rafters, and even the cameraman seemed to miss the punch. Those who saw it swore that that the punch lacked the power to knock over a bowling pin, much less a colossus like Liston. Few believed that Ali had won the fight legitimately.

It is difficult to imagine a time when the name Muhammad Ali did not carry the weight and respect that it does today. But Cassius Clay, as he was called in their first fight, was expected to be defeated, maimed, or even killed by the bad boy from St. Louis.

Liston had awed the world with back-to-back first round knockout wins over crowd-favorite Floyd Patterson in 1962 and 1963. But in 1964 and 1965, Liston would suffer back-to-back losses (a mid-career anomaly in his lengthy string of professional wins). Liston had learned to box in prison, and his 15-inch wrists and sledgehammer fists were infamous. Few believed that he could lose legitimately to a brash upstart who shouted from his second-floor motel balcony: “I am the savior and the resurrection of boxing … You’re looking at history’s greatest fighter. There’ll never be another like me.” Liston simply dismissed the Louisville challenger as “Big Mouth.” With all that was said, it was a total surprise to both boxers when the fight ended so quickly.

As most boxers know, direct hits to the chin drop even the best of them. So, if some boxing aficionados are still not convinced that Ali truly floored Liston, what is it that leads them to believe that the punch or the fight was part of some dark scheme?

Early in the introduction, author Rob Sneddon addresses the first point of the book, and I agree with him, that the punch known as the “phantom punch” was a counter punch that did indeed knock Liston down. “The sequence began, when Liston threw a left jab, his signature punch. Ali ducked away from it, and the punch barely reached his chest. Liston’s awkward forward momentum, combined with Ali’s quick downward counterpunch, added up to a legitimate knockdown.” Footage from the fight shows that Ali’s right cross delivered directly to Liston’s chin as he was coming in snapped his head. And as most boxers know, direct hits to the chin drop even the best of them. So, if some boxing aficionados are still not convinced that Ali truly floored Liston, what is it that leads them to believe that the punch or the fight was part of some dark scheme?

The second point in the title answers that question. It is the story behind the fight and the meat of the book. While it might be overstating the matter to say that this particular fight is the “most controversial bout” in boxing, because the history of boxing is filled with many controversial fights, Sneddon’s book merits our attention in that he craftily details the context necessary to fully appreciate the Ali-Liston fights of the ’60s, particularly their second fight. And it is this story that is really interesting. It will remain for each reader to decide if this chain of events led up to a fight that was fixed.

In their first fight, Liston did not come out for the seventh round and thus gave away his title. He said that he had hurt his arm, but the Miami crowd was skeptical. Doctors later confirmed a torn left biceps tendon. (I am sympathetic with this injury because my father, who boxed professionally during the Great Depression, suffered the same torn bicep which rendered his left arm essentially useless.) But critics suspected a “fix.” Boxing in the Fifties had been notoriously connected to and manipulated by the mob. And Liston, who started his professional career in 1953, had been promoted by a series of questionable characters.

Ali was not without his own controversy. When he first met Liston in the ring in February of 1964, he was known as Cassius Clay, a man who had grown up as a Southern Baptist. Sometime between the two Liston fights, Clay joined the Nation of Islam (NOI), changing both his faith and name, when the group’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, offered him the name of Muhammad Ali. Many Americans then had never encountered a Muslim, and when the two men met in the ring in 1965, the crowd did not know who to root for: an ex-con with mob ties or, as one writer noted, the Anti-Christ.

Neil Leifer’s photo has become the most recognized sport photo of the 20th-century. Yet few fully realize the real drama going on in the ring at that moment. If you ask the same people who recognize Ali in the photo to name the man on the canvas or to name the fight, few will be able to do so. Fewer still can name the city or state where the fight occurred.

The setting was tense. Sneddon quotes the worried promoter, “You’ve got Sonny Liston, who’s supposedly owned by the Mob. …And on the other hand you’ve got Cassius Clay/Muhammad Ali, who’s aligned with Elijah Muhammad, whose people are accused of assassinating Malcolm X, and now Malcolm X’s supporters want to assassinate [Ali].” (Malcolm X had been assassinated by members of the NOI at the Aududon Ballroom in Washington Heights in February 1965, a mere three months before this fight. Feelings between different factions of black American Muslims at the time were running very high.) While some may have shunned the fight, fear didn’t keep the boxing celebrities from coming out. Among the attendees were ex-heavyweight champions James Braddock, Floyd Patterson, Jack Sharkey, Rocky Marciano, and Joe Louis.

Amid all the ballyhoo, had it not been for a young photographer on assignment for Sports Illustrated, the second Ali-Liston fight might have been all but forgotten by the general public. But today, most Americans correctly identify Muhammad Ali in the iconic photo wearing short white trunks and standing defiantly over his vanquished foe laid out flat. Neil Leifer’s photo has become the most recognized sport photo of the 20th-century. Yet few fully realize the real drama going on in the ring at that moment. If you ask the same people who recognize Ali in the photo to name the man on the canvas or to name the fight, few will be able to do so. Fewer still can name the city or state where the fight occurred.

Until now, the location of the fight remains one of the mysteries in the lineage of famous boxing matches. None of the cities one would expect was willing to host the fight: New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Miami, Los Angeles, or Las Vegas. Instead, the fight was held in Lewiston, Maine, in a community hockey rink. In the weeks before the fight, the story made comedic fodder for The Tonight Show’s Johnny Carson. Liston said that he didn’t care where he fought Ali, “even if it’s Vietnam.” Ali said he would fight Liston, even if they staged it in a phone booth. (Yes, there were phone booths back then.)

The location of the fight is important, and it took a regional journalist and baseball writer to explain the significance. What began as Sneddon’s research for an article on Lewiston in 2004 for the Maine magazine, Down East, eventually became The Phantom Punch, the first book published by Down East Books of Camden, Maine. In his research, Sneddon uncovered little-known facts about the interesting people who found themselves in the right place at the right time, enabling them to bring a world championship fight to an old textile town in the Northeast populated by French Canadians.

In his discussion of Bob Nilon, President of Inter-Continental Promotions, a small town concessionaire with big dreams, Phantom Punch resembles other great stories where an unlikely businessman grabbed the opportunity to put a little-known town on the big fight map using the most famous names in boxing. Ali and Liston in Lewiston, Maine in 1965 ranks right up there with stories about Judge Roy Bean who brought Bob Fitzsimmons to a sandbar in the Rio Grande River outside Langtry, Texas in 1896; Tex Rickard who brought Joe Gans to a mining town in Goldfield, Nevada in 1906; and a real estate speculator who brought Jack Dempsey to Indian country in remote Selby, Montana in 1923. (It is interesting to note that while these fights created some wild publicity, none of the promotions produced any significant long-term effects other than bragging rights. Two of the locations remain ghost towns today.)

Rob Sneddon’s style echoes the chaos of those final moments in a 200-word sentence, a run-on by any grammarian’s account, but a brilliant summary of a scene that may have lasted longer than the fight itself.

Because author Sneddon comes to this boxing story as a journalist with an interest in other sports, we find many comparisons to baseball and an original, sometimes startling, take on the people from the boxing world. For example, he calls Nat Fleischer, the venerable scribe of The Ring from the 1920s until his death, “a crusty old magazine editor.” Fleischer stood a little over five feet, and at age 77 he sat ringside at the Phantom Punch fight and yelled to the referee, “He’s out!” His commanding authority was as much a part of the chaos of the fight as the bad prefight publicity, the counter punch no one saw, the lost count of confused celebrity referee Jersey Joe Walcott, and Ali’s refusal to retreat to a neutral corner after Liston went down.

Rob Sneddon’s style echoes the chaos of those final moments in a 200-word sentence, a run-on by any grammarian’s account, but a brilliant summary of a scene that may have lasted longer than the fight itself. Overall, his style is engaging and certainly part of the entertainment value of the story.

In addition to his refreshing style, Sneddon explains why he selects and notes certain information as he does. In the narrative, he calls Clay by his birth name when he covers events before Ali changed his name. And upon finding conflicting detail, Sneddon chooses information nearer to the actual date over information from someone’s memory which may have changed over time. Boxing historians appreciate this acknowledgement, especially when detailed footnotes are absent, as is the case for some journalistic styles.

The one thing that I very much missed was an index. I now have a book marred with marginal notes and without a way to access them. The book also lacks photos, which many readers desire. It would seem especially appropriate to have included any one of Neil Leifer’s photos from the fight. The fact that this is the first book for this publisher may also account for the lack of specificity in the book’s title. Most publishers would have identified Ali and Liston in the title.

By interviewing so many of the fight’s participants and their direct descendants before their information slips away and is lost to us forever, Rob Sneddon has added remarkably to the history of boxing. Phantom Punch is a gem of a book that leaves us with even more to ponder about these fighters, this fight, and boxing in general. If Nick Tosches has written the definitive biography of Sonny Liston (The Devil and Sonny Liston, 2000) then Rob Sneddon has written the definitive account of the second Ali-Liston fight.