The Uneasy Past of the Veiled Prophet Organization

The story of St. Louis’s celebration of exoticism and privilege.

By Kelsey Klotz

January 24, 2018

Within the past five years, some American cities have begun to reckon with symbols of their pasts, viewing historical monuments within present-day contexts. In 2015, just one month after Dylan Roof killed nine members of Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, the South Carolina state government removed the Confederate flag from its statehouse grounds. In late 2016, a Confederate monument was moved from Louisville, Kentucky, to nearby Brandenburg, Kentucky. There was the removal of four Confederate monuments in New Orleans, which culminated in the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee in May 2017. Over the summer of 2017, the city of St. Louis and the Missouri Civil War Museum removed its own Confederate monument in Forest Park.[1] Perhaps most infamous was the August 11 and 12, 2017 march on Charlottesville, Virginia, in which hundreds of people affiliated with white nationalist, white supremacist, and “alt-right” groups gathered, ostensibly to protest the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee, which I wrote about previously.

These reckonings with the racist past of the United States offer a glimpse into how the histories surrounding an event, a place, or an object can shift within different contexts. Ultimately, history is made up of such events, places, people, and objects made meaningful—worth remembering, writing down, or passing on—to people; as that meaning shifts, so too does the historical narrative. For communities who view such symbols as reminders of an exploitative and oppressive system, the removal of Confederate flags and monuments represents a tangible outcome of present-day reckonings of historical injustice: while racism is clearly not wiped out simply with these objects’ removal, symbols of a racist heritage no longer occupy public spaces, which for some is a small symbol of progress. For others, allowing the statues to remain is the way to force uncomfortable conversations that result in persistent encounters with legacies of racism whose effects remain tangible. And still others refute the claim that such a change in historical perspective is needed at all. In each case, Confederate monuments are a point of public reckoning with the past, and its importance to the present, of a city.

In learning about one of St. Louis’s oldest and perhaps best known exclusive societies, I recently had a reckoning of my own, one that continually causes me to question my own place within the city and my relationships with its people and places.

But not all reckonings are public, resulting in changes to how a city collectively remembers a war. Some are private, instead inviting individuals to consider the meaning of events and places they love—events and places whose history, once unveiled, complicate notions of the past and relationships with the present. In learning about one of St. Louis’s oldest and perhaps best known exclusive societies, I recently had a reckoning of my own, one that continually causes me to question my own place within the city and my relationships with its people and places. This is not a story about St. Louis’s ties to the Confederacy (though there are Confederate ties in this story). Nor is it about racism (though racism and classism are crucial to the plot). Rather, this essay focuses on how past contexts inform present-day understanding, taking St. Louis’s Veiled Prophet Organization (VPO) as its case study.

This is the first of a two-part essay focusing on one particular segment of St. Louis’s history, the VPO, that reveals 140 years worth of networks and celebrations of power. In this essay, I introduce the Veiled Prophet Organization, providing a brief overview of its origin as a society that celebrated the wealth and power of its members. In the second part, I will pay particular attention to the relationship between the organization and race, focusing on the organization’s later history to illuminate the ways in which the connections between whiteness and power are often obscured.

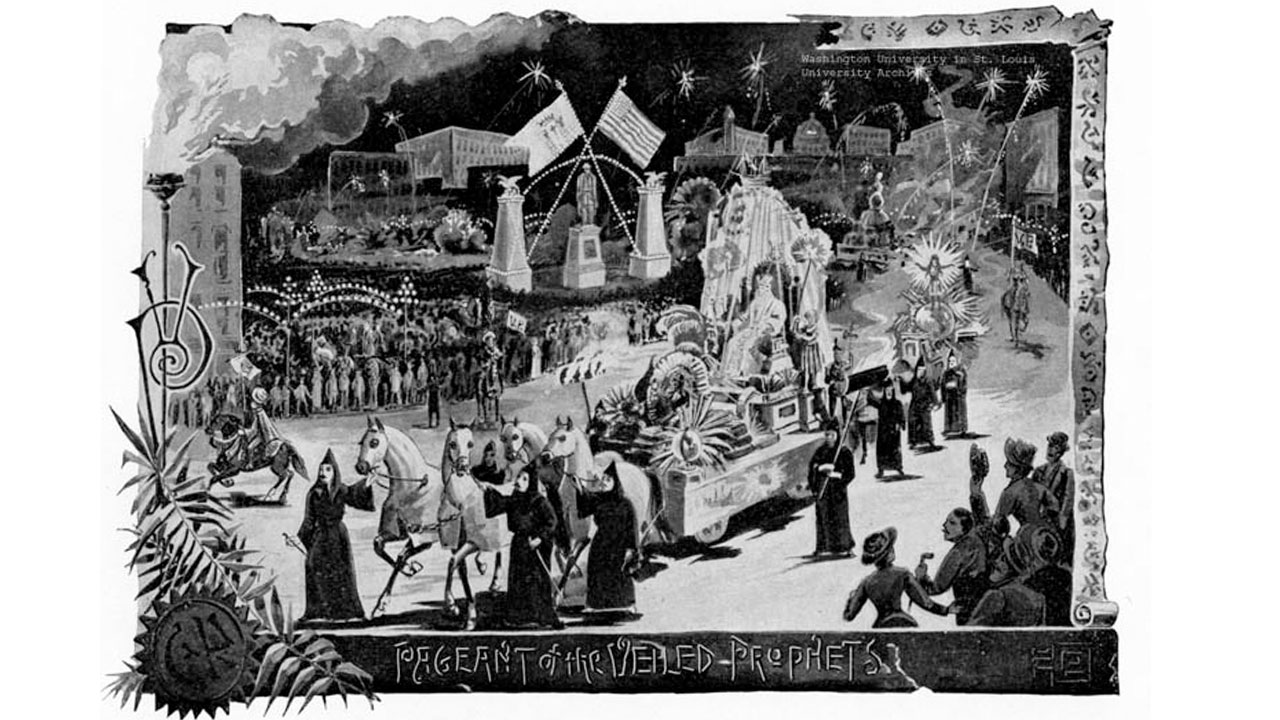

The Veiled Prophet Organization (VPO) was founded in 1878 by fourteen prominent St. Louis businessmen; many attribute the idea of the Veiled Prophet (VP) to Confederate Colonel Alonzo Slayback and his brother, Charles Slayback, a New Orleans grain broker who was a Confederate cavalryman. Later that year, 200 more influential men were invited. The VP first instituted a parade and a ball, over which the Veiled Prophet himself presided. The VP Parade, which featured one unknown member each year who was secretly dressed as “the veiled prophet,” was ostensibly meant to generate pride and interest in St. Louis as a major city. At the ball, the daughters of VP members were presented, and the VP selected one to reign as Queen of Love and Beauty (the first VP queen was Alonzo Slayback’s daughter, Susie Slayback). The common historical narrative is that the VP’s founders initiated the organization to create an annual celebration of St. Louis similar to that of Mardi Gras in New Orleans (in fact, the first parades featured floats purchased by members of the VPO from past New Orleans Mardi Gras celebrations).

Like the Veiled Prophet of Lalla Rookh, St. Louis’s VP was a veiled, wealthy man from the East who expected and was indeed rewarded with opulent receptions wherever he went—but that is ultimately where the similarity ends.

The Slaybacks took the name and myth of the Veiled Prophet from a poem by Irish author Thomas Moore titled “The Story of the Veiled Prophet of Khorassan,” found in the book of poetry Lalla Rookh, published in 1817. Though likely not well-known now, Lalla Rookh was successful in the nineteenth century; by 1841 twenty editions had been published, and in the nineteenth century the poem was adapted into a variety of musical settings, including operas by Anton Rubinstein and Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, and a choral-orchestral work by Robert Schumann. Like the Veiled Prophet of Lalla Rookh, St. Louis’s VP was a veiled, wealthy man from the East who expected and was indeed rewarded with opulent receptions wherever he went—but that is ultimately where the similarity ends. The St. Louis VP is meant to be a benevolent ruler, a “beloved despot, evasive but real,” who, as a 1928 book published by the VP explains, “rules with an iron hand encased in velvet.” Such descriptions also highlight the VP’s expectation for complete authority over those beneath him. The fact that the VP’s identity alternates between members yearly suggests that each of the men expect that same authority.

However, the Veiled Prophet of Khorassan from Moore’s poem represents an entirely different message that is worth exploring. Mokanna, the Veiled Prophet of Moore’s poem, is a false prophet, whose veil hides a hideous face. According to Jeffery Vail, professor of English literature at Boston University, “The Veiled Prophet of Khorassan” represented Moore’s disappointment in the “degeneration of the French Revolution’s egalitarian and democratic promises into anarchy and terror” (i.e. the Reign of Terror following the French Revolution), which Moore saw “as a tragic betrayal of a noble cause.” The Veiled Prophet Mokanna, Vail argues, is “most accurately seen as a representation of radical Jacobinism, concealing its moral deformity behind a beautiful mask.” Mokanna is, indeed, surrounded by pomp and opulence, which serve to win others to his cause. As if to cement his true depravity, Moore’s Mokanna rapes and corrupts the beautiful and virtuous high priestess Zelica, who inspired the St. Louis’s Queen of Love and Beauty.

Maybe the original VPs never fully understood the story of Mokanna, the veiled brute. Maybe they purposefully took the elements they liked—the spectacle, the exoticism—in order to create a mystical and mysterious symbol that could cloak their wealth in moral good.

Ultimately, the VP changed the history of the Veiled Prophet from one of moral deformity to one of moral rectitude, using the accumulation of wealth as a symbol of their own righteousness (never mind the original VP members’ roles in perpetuating low wages and unsafe working environments in St. Louis, which I discuss below). Maybe the original VPs never fully understood the story of Mokanna, the veiled brute. Maybe they purposefully took the elements they liked—the spectacle, the exoticism—in order to create a mystical and mysterious symbol that could cloak their wealth in moral good. Either way, 140 years later, the VPO remains, and its success and survival is, much like Confederate monuments across the United States, the result of intersecting race, class, and gender-based ideologies that kept the image of power in St. Louis within a select cadre of men.

Assuming neither the original VPs nor the current VPs intended to associate themselves with a hideous and degenerate rapist, the connection between the St. Louis VP and that of Moore’s poem seems to have been rooted in a combination of wealth, power, and mystique. The first image of the Veiled Prophet, published in the Missouri Republican in 1878, suggests that early on, these three elements formed the “iron fist in the velvet glove” of which the VP itself boasted. In it, the Veiled Prophet, wearing an all-white gown, pointed hat, and mask, stands with a pistol and two shotguns. This image was a short-lived representation of the Veiled Prophet, and based on my research, the VP never appeared armed in a parade or at a ball. The second Veiled Prophet image, from 1883, and current photos of the Veiled Prophet look more like a cross between a Norse God and the Pope—imagery with fairly obvious connections to whiteness, but that are ostensibly more linked to benevolent forms of power.[2]

Woodcut of the Veiled Prophet, Missouri Republican, 1873.

It is difficult not to immediately link the 1878 image with that of a Klansman; however, the Klan did not develop the uniform of white robes and hoods until its revival period beginning in 1915 (inspired by the film The Birth of the Nation), nearly 40 years after the initial woodcut of the Veiled Prophet. Still, this image remains connected to the VP, thanks in large part to historian Thomas Spencer’s book, The St. Louis Veiled Prophet Celebration: Power on Parade, 1877-1995, and a recent Atlantic article.

The first image of the armed VP may have suited the initial VP members, who sought to create a visible manifestation of their control over the city. Spencer argues that in addition to attempting to boost trade on the Mississippi and reclaim St. Louis’s status as a major modern city, the VP had another motive. Spencer writes that VP members were likely compelled by the Railroad Strike of 1877 to re-institute class hierarchy by demonstrating the power and opulence of the wealthiest and most prominent businessmen in the city, putting working-class strikers in their place.[3] Following years of wage cuts, white and black rail workers began a week-long strike in St. Louis in 1877; this strike inspired workers across industries to protest for an 8-hour workday and a ban on child labor. The strike ended after 3,000 federal troops and 5,000 deputized special police forced the strikers to disassemble, during which time eighteen strikers were killed.

The first image of the armed VP may have suited the initial VP members, who sought to create a visible manifestation of their control over the city. Spencer argues that in addition to attempting to boost trade on the Mississippi and reclaim St. Louis’s status as a major modern city, the VP had another motive.

The first Veiled Prophet, and the only prophet to be willingly revealed, was St. Louis Police Commissioner John G. Priest, who had taken an active role in the railroad strikes’ violent end. Therefore, despite the VPO’s pomp and circumstance celebrating the city of St. Louis, Spencer argues that the enforcement of a class hierarchy following the strikes was made clear through Commissioner Priest’s prominent position in the spectacle. Put another way, when working-class St. Louisans took strides to earn more money, achieve upward mobility, and attain a measure of the relationship between wealth and morality propagated by the VPO, it was the members of the VPO who put a stop to it.

Wealth was a primary defining feature of the VP’s membership and its power. According to the myth, the Veiled Prophet is a mystical traveler from the ambiguous East who decided to establish St. Louis as a beautiful city. The fact that St. Louis was chosen was meant to be indicative of its worth and value as a city based in the grand traditions of the Old World, but prepared to progress to the New World. As Spencer explains, for members of the VP, progressing to the New World meant success in industry and the wealth that ultimately followed. This remains a familiar narrative (see Iowa Senator Charles Grassley’s comments regarding the repeal of the estate tax in the recently passed “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act”): those that work hard make money and have judiciously saved their money, whereas those without money must have spent it on vices, or they had not worked hard enough to earn it in the first place. At first, the patronizing and self-congratulatory message of the VPs was fairly obvious: the first VP parade had an educational/propagandistic theme, and featured seventeen floats. Each float demonstrated the evolution of mankind from its beginnings to when the VP designated St. Louis as his second home. The second-to-last float was titled Wealth, and on it sat Minerva, goddess of wisdom and protectress of industrial arts, upon a huge silver dollar. Spencer argues that such imagery was a clear reminder for parade-goers, who represented St. Louis’s lower and middle classes, that success in industry—and life, for that matter—went only to those both wise and worthy. To be worthy, one must be industrious. Consequently, their workers or subordinates who lacked wealth must have been neither wise nor worthy (32).

Make no mistake: the VP was a socially exclusive club that saw its members as the fathers of St. Louis. To join, the first members paid a $100 initiation fee, which was roughly 1/6th of a workingman’s yearly wage. As the group developed through the twentieth century, Spencer explained to The Riverfront Times in 2000 that the same families remained part of the group and maintained their hold on the monopoly of power in St. Louis: “By the 1950’s and 1960’s, all the corporate CEOs in St. Louis had the same names as the major business leaders did in the 1880’s.”

While the parades and balls were successful through the 1960s (the balls and parades were even televised at mid-century), by the late 1970s, the VP-sponsored events seemed to be sagging under the organization’s bad press. In an attempt to again rejuvenate St. Louis’s image, as well as that of the VP, the group organized the VP Fair in 1982 in downtown St. Louis, using only the initials and not the full name. Held July 4, the fair was linked to patriotism, and called “America’s biggest birthday party.” That tagline, along with the parade’s similar tag, “America’s birthday celebration,” remains today.

The VP highlights the ways in which past, present, and future contexts collide, and are inseparable within the landscape of a city. The past power of the VPO’s members is inscribed across St. Louis’s buildings, institutions, and street names …

The VP is a symbol of St. Louis’s past, created in a time in which exoticism was a fad. The organization’s pageantry and mysticism, along with its ostensible link between affluence and morality, self-consciously highlighted the families who are credited with St. Louis’s growth. But the VP was always meant to be a symbol of St. Louis’s present and future. Formed just after the Reconstruction Era, the stated purpose of the VPO was meant to advertise St. Louis as a modern city—a city with great potential whose civic leaders could shepherd it into the new century. The VP highlights the ways in which past, present, and future contexts collide, and are inseparable within the landscape of a city. The past power of the VPO’s members is inscribed across St. Louis’s buildings, institutions, and street names (some of the VP’s best-known members include Kemper, Busch, Schlafly, Danforth, and Schnuck), but their longevity demarcates VP members’ influence across generations.

In the second part of this essay, to be published next month, I investigate the specifics of the organization’s troublesome racial history, and in particular, how the VP’s image of whiteness has impacted some St. Louisans, while remaining invisible to others. In next month’s essay, I explore the ways in which whiteness hides itself in organizations like the VPO, ultimately making whiteness invisible and therefore innocuous to those who benefit from it.

1] Commissioned in 1914 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the monument is titled “The Angel of the Spirit of the Confederacy,” and is currently being housed in an undisclosed location. The Missouri Civil War Museum oversaw the removal and storage.

[2] Spencer notes that the VP organization was much more tied to white Protestants than to Catholics.

[3] Thomas M. Spencer, The St. Louis Veiled Prophet Celebration: Power on Parade, 1877-1995 (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2000).