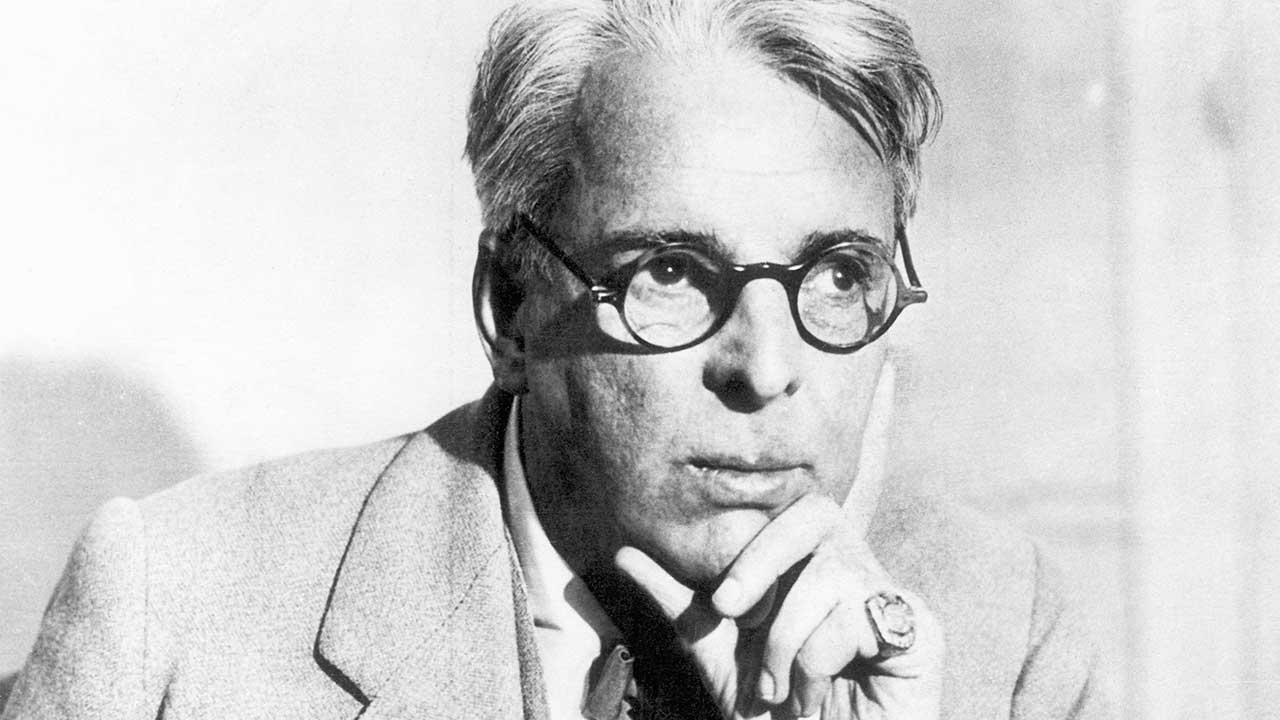

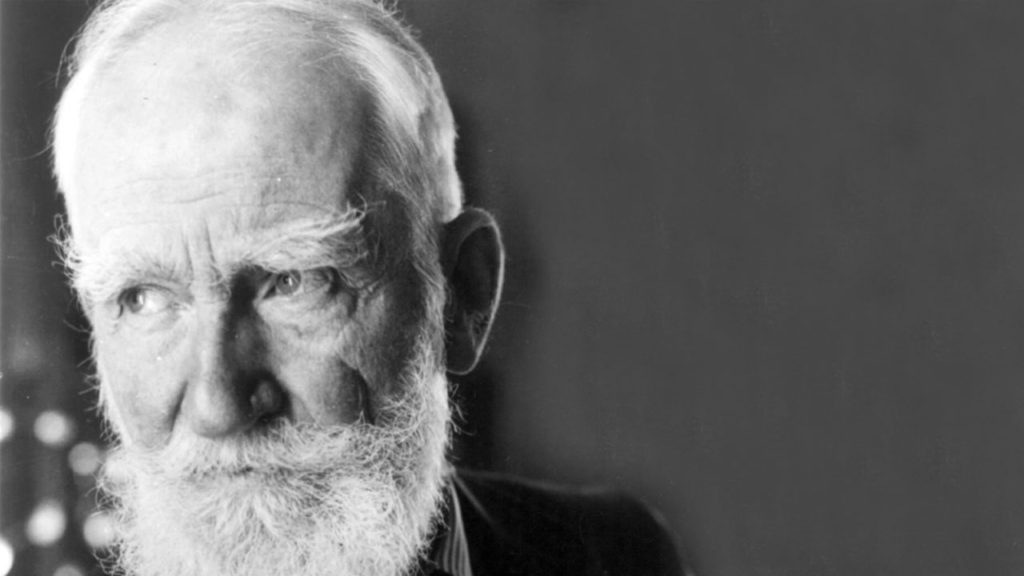

In Axel’s Castle (1931), Edmund Wilson wrote that Yeats believed that the more a mind is on fire, the more creative that mind is, the less will he look at the external world or value it for its own sake. It provides him with metaphors and with examples, no more than that. Indeed, he even is “a little scornful of it.” Wilson contrasts Yeats’s “A Vision” with the “Guide to Socialism and Capitalism” by “that other great writer from Dublin,” George Bernard Shaw. While Shaw assumed the burden of “the whole unwieldy load” of contemporary sociology, politics and economics, biology and medicine and journalism, Yeats turned away, convinced that science and politics were “somehow fatal to the poet’s vision.” Yeats hated Arms and the Man (1894). Wilson wrote: the poet had a dream in which Shaw appeared to him “in the form of a sewing machine, ‘that clicked and shone, but the incredible thing was that the machine smiled, smiled perpetually.’”

If Shaw, who took “the whole unwieldy load” of sociology and the rest upon his shoulders, appeared to Yeats as a clicking and shining and perpetually smiling sewing machine, what form might the quantitative social scientists and systems theorists of today have taken in the poet’s dream? At least Shaw was making drama from the raw materials of that outer world Yeats turned his back upon, not dismembering whole persons and treating severed parts to multivariate manipulation. He was not liquidating human beings by dissolving them into granules of data and then packing them into concepts and theories, and then reifying them into the bargain, before serving them up as Truth and Reality. It is plain that radical empiricists of any stripe are anathema to the literary imagination.

If Shaw, who took “the whole unwieldy load” of sociology and the rest upon his shoulders, appeared to Yeats as a clicking and shining and perpetually smiling sewing machine, what form might the quantitative social scientists and systems theorists of today have taken in the poet’s dream?

So, some might say, is yielding to the temptation to think too much? In the Savage God (1971), A. Alvarez tells us Coleridge “deliberately poisoned his creative gifts by an over-dose of Kant and Fichte, because to survive as a poet demanded an effort, sensitivity and continual exposure to feeling which were too painful for him.” The slow murder of the daimon within was begun by the study of metaphysics and was finished by taking opium. As far as writing poetry is concerned, ‘the last thirty-odd years” of Cole-ridge’s life “were a posthumous existence.” Poet and philosopher contend today as they have done long before Plato’s time—sometimes within the soul of the writer. I was intrigued to read in a letter Louise Bogan wrote to Karl Shapiro that now that she was over the age of 50, “stray wisps of theory” were forming in her mind. Her words brought to mind an observation made by Thomas Babington Macaulay in his essay on Milton in Essays and Biographies: “In proportion as men know more and think more, they look less at individuals and more at classes. They therefore make better theories and worse poems.”

Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw

“Thou shalt not sit/With statisticians nor commit/A social science.” So Auden admonishes in his poem “Under Which Lyre.” Suppose that thinking in abstractions and categories and chasing those “stray wisps” of theories are the norm as one grows older? I am aware that even to contemplate this is to begin to commit a social science. But I am also aware that Auden’s warning about being watchful of the company one keeps commits the very same sin. (The “bad companions” hypothesis, as it was called long ago in criminology, is in its turn based on a bit of folk wisdom that is invoked by most parents during their offspring’s adolescence.)

Some works of fiction I will not name here do seem to be the harvest of that posthumous existence of a poet who died by his own hand. But I think Auden’s admonition would apply to many more fiction writers than would the cautionary tale of Coleridge’s later years. It seems to me that more short story writers and novelists are after bigger game than the metaphors and examples Yeats thought was all the outer world is worth. A fiction writer who elected to study social science rather than a sociologist who studies literature, I may have a few stories to tell in my memoirs about living in both worlds simultaneously for many years. I confess being a double-agent (or schizophrenic) who was for a time a card-carrying member of both the Modern Language Association and the American Sociological Association. Given the consonances between many works of fiction and social science, I regret to have found that quite a number of inhabitants of the two cultures were inclined to shun one another, and that when they do meet, all too often it is to exchange hostilities. These days, the indifference of some fiction writers and sociologists to one another’s publications is hardly polite. I have found that if you let it be known at the ASA convention that you also attend the MLA meetings, or vice versa, some people from either association who recognize the acronym of the other might accuse you of spying—or ask if you are slumming.

Tribalism seems to be alive and well in the groves of academe. It is true that inter-disciplinary studies on a number of campuses throughout the country even today, whether housed in a department under that name or taught through programs in American Studies, Bilingual Education, Black Studies, Jewish Studies, Women’s Studies or others, are managing to survive. However, after a quarter of a century of teaching sociology at Louisiana State University, anthropology at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa, and then sociology at SUNY, New Paltz, I have observed that all too often people in different departments talk past one another, and that the silence between members of English and Sociology is particularly resounding. This may be the same for psychologists and English professors as well. In her essay in The New York Times Book Review on January 29, 1984, “Why Scholars Become Storytellers,” Frederika Randall writes that there is greater evidence of enthusiasm for a literary model of social inquiry among historians and anthropologists than among sociologists and psychologists. She reports that Howard Gardner finds it a paradox that his fellow psychologists have not been sensitive to the ways they construct their narratives, “since this is not their territory.” And she quotes Richard Bennett, a sociologist who is also a fiction writer, as observing that sociology “has gone back to the old quantitative, positivistic ways of the 1950s.” Turning Lionel Trilling’s prediction that sociologists will become the novelists of our time on its head, Bennett said, “unfortunately, it is the novelists who are the sociologists of our time.”

These days, the indifference of some fiction writers and sociologists to one another’s publications is hardly polite. I have found that if you let it be known at the ASA convention that you also attend the MLA meetings, or vice versa, some people from either association who recognize the acronym of the other might accuse you of spying—or ask if you are slumming.

Fifty years ago, there were writers and social scientists who gladly learned from one another’s works. For example, in A Peculiar Treasure (1938), Edna Ferber acknowledged a considerable debt to a classic work in sociology which she read when working on her novel American Beauty (1931). “The incidental reading was an education,” she recalled. The “two enormously fat blue-bound volumes” of The Polish Peasant in Europe and America [1918] were more absorbing and exciting than any fiction I’ve read in years.” Zora Neale Hurston, a writer who bridged the oral and written traditions as well as the heritages of folklore, anthropology and literature, moved with ease between the worlds of letters and of social science throughout her life. It may not be too much to say that in academe, Columbia University was the Fertile Crescent for exchanges between writers and social scientists at that time. Margaret Mead recalled in An Anthropologist at Work: Writings of Ruth Benedict (1959) that when Benedict held an assistantship under Ogburn’s direction, she “filled his office with working poets,” among them Louise Bogan. In 1922, Bogan did cataloguing work for Ogburn, who was then professor of sociology at Columbia. Bogan and Ruth Benedict were friends for many years. And Bogan knew and admired Edward Sapir, who was chief of the division of anthropology at the Canadian National Museum. Sapir was so accomplished a poet that a group of his poems appeared in the January 1925 issue of The Measure. Shortly thereafter, he began publishing poems and reviews in Harriet Monroe’s Poetry, the most prestigious literary journal of the day. Mead herself had strong literary inclinations. She wrote in her autobiography Blackberry Winter: My Earlier Years (1972)that it was not until she met the more gifted Léonie Adams at Barnard that she decided that writing poetry would be her avocation; and that she and her friends exchanged poetry as naturally as they exchanged letters. Benedict, who had been Boas’s teaching assistant when Mead first took the course he offered in her senior year at Barnard began studying anthropology in her thirties. One nom de plume Benedict assumed was Anne Singleton.

There was, however, a counter-current to this “collaborative research,” as it was called by its founders. Randall reports in “Why Scholars Become Storytellers” that Louis Langness, professor of anthropology at UCLA, “surveyed fiction written by American anthropologists and concluded that novels, stories and travel accounts were accepted as part of the ethnographic record up until the 1930’s, when the profession began to define itself as a science.” The 1930s also was a time when many American writers proclaimed the superiority of fact over fiction. William Stott notes in his Documentary Expression and Thirties America (1973) that, between the beginning of the Depression and the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Theodore Dreiser did not publish any fiction, and wrote very little of it. “How can one more novel mean anything in this catastrophic period through which the world is passing?” Dreiser asked, and went on to say, “No, I must write on economics.” Stott recalls that “even Wallace Stevens, that most aesthetic of writers, felt the tendency.” In 1936, Stevens declared, “The social situation is the most absorbing in the world today.” He felt that the Great Depression, and after that the war, had shifted people’s attention “in the direction of reality, that is to say, in the direction of fact,” and he approved of this. “In the presence of extraordinary actuality,” he said, “consciousness takes the place of imagination.” A number of writers of that period believed that writing fiction was “too frivolous an activity for a time of social cataclysm,” and they turned from artistic work to the production of what in Dreiser’s case Daniel Aaron called “journalistic ephemera.”

Fifty years ago, there were writers and social scientists who gladly learned from one another’s works. … Zora Neale Hurston, a writer who bridged the oral and written traditions as well as the heritages of folklore, anthropology and literature, moved with ease between the worlds of letters and of social science throughout her life.

Again, in the 1950s, Hortense Calisher recalls in her essay in the September 30, 1975 New York Times on “World Violence and the Verbal Arts,” that writers were gravely told, as if this were a law, “that the novel was dead, poetry dying, and all verbal art shortly to follow, since imagination, against the violence of the present world, had no force worth considering.” The “miserable fact” was now where all power resides, and from now on, “would be all that serious people wanted to hear.” Like Dreiser and Stevens in the 1930’s, Calisher made a clear distinction between fact and fiction. When the age-old issue was raised in the 1960’s, an uneasy truce was declared by writers of “faction.” John Hallowell writes in Fact and Fiction: The New Journalism and the Nonfiction Novel (1977) that, given the apocalyptic mood of that decade, everyday ‘reality’ became more fantastic than the fictional visions of even our best novelists.” The publication of some novelists and journalists reflect “an unusual degree of self-consciousness about the writer’s role in society and the unique character of American life.” The old proclamation that the novel was dead was sounded once again. It became ever more difficult for some writers to say what “social reality” is, and the society seemed so protean to them that “the creation of social realism seemed continually to be upstaged by current events.” In 1961, Philip Roth wrote of how difficult it was for the mid-20th century American writer to understand, describe and then make credible much of the American reality. In Cannibals and Christians (1966), Norman Mailer wrote that the literature of American social realism “grappled with a peculiarly American phenomenon—a tendency of American society to alter more rapidly than the ability of its artists to record that change.”

Many consonances in works of fiction and social science are noted in Morroe Berger’s Real and Imagined Worlds (1977), among them correspondences between novels by George Eliot on the one hand, and works by Robert Michels and Robert MacIver on the other.

My own reading on the subject in the series Writers at Work: The Paris Review Inter-views, led me to make a few discoveries about the choice between the two vocations.

Saul Bellow, who studied anthropology, never completed the requirements for the master’s degree in that subject because, he said, as he was writing his thesis, it kept turning into fiction. Nelson Algren, recalling his student days at the University of Illinois, said he had been “moved by a course given by a sociologist named Taft” that inspired him to think about becoming a sociologist. However, he said, it would have been impractical to do so because there were no job opportunities for sociologists at the time. Furthermore, “in order to become a sociologist, I guess I would have had to take a Master’s degree.” Since Algren had to borrow money for tuition, “there was no question of going further.” Algren, who left college in 1931, drew a contrast between writing fiction and social science, to the disadvantage of the latter. Remarking of another writer that he is “too journalistic for my taste” and that “I don’t get anything besides a social study” from reading the work. Algren said, “It isn’t enough to do just a case study, something stenographic.”

Like Bellow, Kurt Vonnegut studied anthropology. Vonnegut’s 1971 address to the National Institute of Arts and Letters took the form of a testimonial to the anthropologist Robert Redfield’s “folk society.” On the other hand, William Foote Whyte is an example of a social scientist who thought seriously of becoming a writer. He had “two strong interests” when he was a student at Swarthmore, he wrote in his classic study Street Corner Society (1943), and these two were economics “sometimes (mixed with social reform) and writing.” Whyte wrote short stories and one-act plays in college, and attempted to write a novel. But he “felt uneasy and dissatisfied” with his creative writing because he was unable to escape the confines of his immediate experience.

He decided that, if he were able to write anything worthwhile, he would have to transcend the narrow social borders that, up to that time, had bounded his life. I think of Street Corner Society as his travel book about that outward-facing journey.

There are other sociologists in addition to Bennett who have written fiction, among them Peter Berger and Everett Hughes; among the anthropologists are Clifford Geertz, Laura Bohannan, Elsie Crews Parsons, Elenore Smith Bowen, Robert Redfield and Claude Lévi-Strauss, who includes an original play in his Tristes Tropiques. Alfred Kroeber studied literature before deciding to become an anthropologist. As sometimes happens in life, his children followed the road he had not taken: his son is a professor of English, and his daughter is the fiction writer Ursula K. LeGuin. But there are social scientists and writers who cast a cold eye upon another’s works. Saul Bellow recalled that Herskovitz, with whom he had studied African ethnography, rebuked him for having written the novel Henderson the Rain King. The subject, Herskovitz chided, was far too serious for the “fooling” that Henderson seemed to represent—“fooling” that, for Bellow, was serious indeed. There are social scientists who think that writing fiction is frivolous, and that if one has serious intentions, one ought to try to repair the world or at least make it more intelligible. That this is just what fiction writers are trying to do apparently is incomprehensible to them. On the other side are fiction writers who express contempt for the work of social scientists. Hortense Calisher writes in her autobiography Herself (1972) that “Sociology is for the simple-minded.” Calisher, who is a self-declared “enemy of any who look at literature topically,” put the matter graphically, if rudely. “In the zoo of the social sciences is where the musk-glands of humanity are removed—for study. A novel doesn’t study—it invents. Inevitably, it represents.”

Inevitably, however, so does social science “represent.” And imagination is as indispensable to the writer of works of social science as it is to the fiction writer. In Everything In Its Path (1972), his book about the Buffalo Creek flood, Kai T. Erikson used the method of the case study. Like James West in Plainville and Whyte in Cornerville, Erikson wanted to “get the feel of things” first, and was drawn to “the nearest thing” to a street corner in Buffalo Creek, Charlie Cowan’s gas station, as a good observation post. He read about disasters as a class of events; he studied the transcript material that had been compiled for the legal action to be taken on behalf of the survivors. He asked people questions; he listened to their conversations. He observed them as they went about the business of their daily lives—or what, after the disaster, was left of them. In his analysis, he reasoned from the observed fact to concepts and thence to theories. But Erikson also studied children’s drawings (as did Robert Coles for his Children of Crisis series 1967-1977) and listened to people recount their dreams. His book weaves passages from Santayana’s The Last Puritan (1935) and Dostoievski’s Notes From Underground (1864)into his account of the disaster and its aftermath. He traced a path inward to people’s testimony of their experience of the disaster and then a path outward again to our common condition. Future historians, he suggests, may find in the “classic symptoms” of trauma manifest in this disaster—the relativism (an absence of fixed moral landmarks and of established orthodoxies), the sense of impotence, the memory overload, the diffuse apprehensiveness—the “true clinical signature” of our age.

Not everyone would go as far as E. L. Doctorow, who declared in his acceptance speech for the National Book Critics Circle Award for the best novel of 1975 that, “There is no more fiction or nonfiction—only narrative.” But my many years of experience in conducting a variety of research studies has persuaded me that social science is art or craft at least as much as science, and that many works of social science, like stories and novels, are a broth of fact and fiction.

Facts or fictions? Everything In Its Path offers the reader much more than generalizations and abstractions. In his review of the book, Michael Harrington said that because of this, the ideas in it “resonate in our minds like poems.” He expressed the hope that social scientists would “take note of the vitality and creativity of which their discipline is capable.” Erickson himself criticized the traditions in which he worked. He faulted conventional social science research methods for failing to “equip one to study discrete moments in the flow of human experience “He thought that “the search for generalization has become so intense in our professional ranks that most of the important events of our day have passed without comment in the sociological literature,” The more one knows and respects a community of people, he wrote, the more difficult it becomes to think of them as instances of a proposition in sociology—particularly if it happens that they are “suffering in some sharp and private way.”

Not everyone would go as far as E. L. Doctorow, who declared in his acceptance speech for the National Book Critics Circle Award for the best novel of 1975 that, “There is no more fiction or nonfiction—only narrative.” But my many years of experience in conducting a variety of research studies has persuaded me that social science is art or craft at least as much as science, and that many works of social science, like stories and novels, are a broth of fact and fiction. Long ago, anthropologist Godfrey Lienhardt noted the temptation, which he thought to be especially strong in the social sciences, “to give a seemingly scientific basis to attitudes and opinions not derived only, if at all, from dispassionate consideration of fact.” My own years of labor in the fields of social science have persuaded me that it does not take much imagination to create the data one wants to have at hand to serve a particular purpose. Many who demand “the facts” about the crime rate or the unemployment rate or the divorce rate or “real” poverty in America are asking to be told what they want to hear. It is only if one provides them with data they do not want to hear that they will challenge one’s research methods. The fact is, there are as many crime and unemployment and divorce and poverty rates as there are ways of calculating them, and each tells a different story about what is the case.

Who, then, is telling the truth about our asylums—historian David Rothman in The Discovery of the Asylum (1971) or sociologist Erving Goffman in Asylums (1961) or writer Ken Kesey in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest? (1962) Is the reality of the social class structure of Newburyport, Massachusetts more clearly represented in Warner and Lunt’s Yankee City series (1941-1959) or in J. P. Marquand’s Point of No Return? (1949) If I want to learn about the wealthy in the eastern United States in the early decades of this century, should I rely more on Edith Wharton’s novels or on Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class? (1899)

Which tells me more about life in the small-town America of our past, the Lynds’ books about Middletown (1929, 1937) or Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street (1920)? Which tells me more about the dilemma of unchecked population growth, Malthus’s grim essay (1798) or Swift’s Modest Proposal (1729)? Is suicide made more intelligible to me if I read Durkheim’s treatise on the subject (1897) or Alvarez’s The Savage God? In that book, the reader is given the consummate reproach of the poet to the sociologist: “All that anguish, the slow tensing of self to that final, irreversible act, and for what? In order to become a statistic.”

I suspect that an exaggerated sense of importance of whatever subject one writes about is a delusion as necessary for getting on with the task as the hubris any writer must commit continually in order to persevere in completing the work. And I also suspect there always will be a creative tension between “facts” and “fictions.” The outer world Yeats spurned can become a vampire of the literary imagination, but it is “no illusion,” Henry James reflected, “no phantasm,” this world we inhabit, “no evil dream of a night; we wake up to it again for ever and ever; we can neither forget it nor deny it nor dispense with it.” The writer strives to make sense of it. It is not going to make sense of itself except perhaps to the happy Hegelians and others of the chosen who already know what it all means before committing the first words to the blank page.

Saul Bellow, who studied anthropology, never completed the requirements for the master’s degree in that subject because, he said, as he was writing his thesis, it kept turning into fiction.

In 1859, when the young George Meredith was summoned to be given Thomas Carlyle’s congratulations on the publication of his first novel, the older man, then in his middle sixties, warned the younger one of the frivolousness of fiction and urged him to turn to history, to “facts.” Meredith declined the invitation. “But facts are truth, and truth is facts,” Carlyle argued. Meredith replied that, on the contrary, Truth was “the broad heaven above the petty doings of mankind which we call facts.” After more years of labor than I care to count, I have come to appreciate this truth also, one Meredith grasped when he still was quite young. And I also have come to understand how it can happen that one deliberately chooses not to consider that “broad heaven” each of us carries inside our lives that vaults above our petty doings day by day. And that the Carlyle in each of us may be charged not with having been found wanting in imagination, but with resisting it. Surely the “facts” by themselves will not save us. But the use of the imagination in whatever work one undertakes to write can be redemptive.

My husband Walter tells me of a character in a picaresque novel, a member of the nobility down on his luck, whose attire is tattered and whose stomach growls from hunger. Yet when he goes forth into the world, he uses with some ostentation a toothpick made of gold. Anthropologist W. Lloyd Warner fashioned six social class boxes into which he thought every inhabitant of “Yankee City” might be fitted—the Upper Upper, the Upper Lower, the Upper Middle, the Lower Middle, the Upper Lower and the Lower Lower. Into which box shall we place this fellow? If we ask him his view on the matter, is there any doubt he knows where he belongs, himself and his gold toothpick? The one truth we do know, the reality we can be certain of, is that if we are to put him into any one of these boxes, we are going to have to kill him first.

• • •

Afterward: This essay was written and presented by me in a program of Faculty Research Seminars at the College at New Paltz New York when I was an adjunct professor in the Department of Sociology and Acting Coordinator of the Women’s Studies Program there, on February 29, 1984. The program spanned a broad range of interests in the fields of the natural sciences, the social sciences and the humanities. The author of Redeeming the Sin: Social Science and Literature, I offer here a retrospective of what I found in my quest for the best of what was thought and said up to that Orwellian year on the differences between Facts and Fictions, Truth and Lies, Virtual and (Actual?) Reality, and what I am still discovering. What is Truth? What is Reality? This essay is an invitation to readers to carry on and forward with me these past 33 years since to the time of Trump (who, we are told, does not read), when these have become burning questions that are not just timely, but urgent. Some of us reading this essay were the last generation crossing the threshold of the Internet, globalization, and the explosion of technology and hi-tech devices, peering into the crystal ball of the future, imagining a far different world emerging from the one we find has become our present moment, when the critic Michiko Kakutani tells us in The New York Times on January 27 this year “Why 1984 Is a 2017 ‘Must-Read’” in this age of “alternative facts.” In his De Rerum Natura, Lucretius writes that “In a brief space the generations pass,/And like unto runners hand the lamp of life,/One unto other.” Shall these bones live? May we read (again) George Orwell’s dystopian novel and works cited in this essay, and may they light our way. And as we retrace our steps down to Avernus and from thence climb as far back up as we are able, may we redeem some portion of whatever of the world remains for the sake of those who come after us.