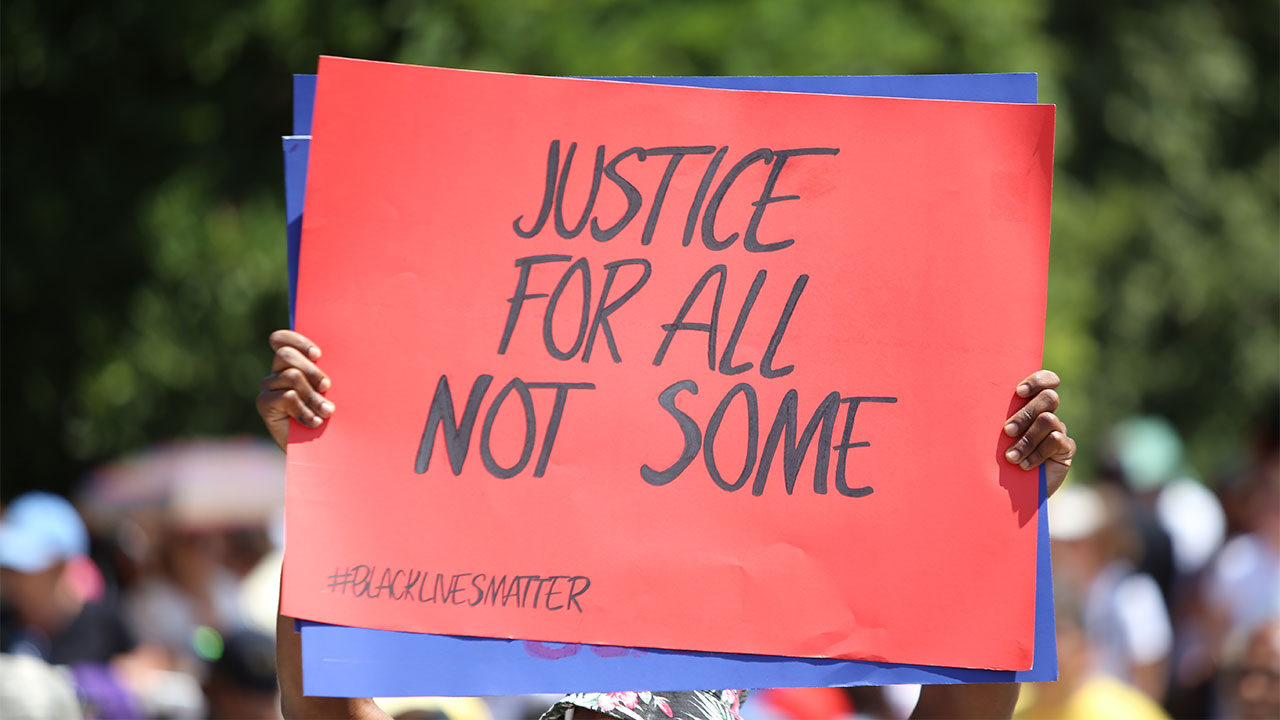

“This is what democracy looks like!” In the fall of 2014, that was a rallying cry here in St. Louis, as activists mobilized to oppose police violence against Black Americans.

The activists were right. Real democracy, or “rule by the people” is not just about voting to elect public officials, campaigning for parties and candidates, and engaging in debates about the issues of the day. It is also about ordinary people—people like the early twentieth-century suffragists, the striking auto workers of the 1930s, the Freedom Riders of the Jim Crow South, and the Black Lives Matter activists of 2020—exercising their political power to fight for change. People are governed, in large part, by laws, institutions, and social practices that are not decided by elections, and that are not the issues of the day. We are governed by structures—like the American criminal justice system—that typically operate in the background of “normal politics.” Ordinary people exercise political power when they politicize those background structures.

Political disruption can interrupt what I call motivated ignorance, an idea that is closely related to motivated reasoning, or the fact that people tend to seek out and to disproportionately weight evidence that supports the beliefs they want to hold.

In my recent research, I argue that disruptive politics are particularly effective at performing this politicizing function. Why? Because political disruption can compel people to pay attention to problems that they would rather ignore. Political disruption can interrupt what I call motivated ignorance, an idea that is closely related to motivated reasoning, or the fact that people tend to seek out and to disproportionately weight evidence that supports the beliefs they want to hold.

But motivated ignorance is about what people are motivated to not know. Specifically, it is about the motivation to be ignorant about one’s complicity in practices that violate important ethical principles. For example, I might be motivated not to know about the oppressive conditions under which the workers who make my clothing labor. You might be motivated not to know about the suffering of the animals whose meat you consume. I like wearing the inexpensive clothing, and you enjoy eating the delicious meat. At the same time, we both want to believe that our behavior is ethically unproblematic, so we avoid, or we ignore, or we fail to direct our attention to readily available evidence to the contrary. If we do, then in that respect we are like many White liberals in this country, who in principle reject racial injustice, yet habitually ignore the structural racism that is the background to American politics-as-usual.

That is where disruption comes in. In the fall of 1951, when the Gallup Poll Organization asked American respondents to name the most important problem facing the United States, less than half of one percent gave answers like “civil rights,” “racial problems,” or “discrimination.” And those results were fairly typical. Every month, Gallup poses the “most important problem” question to a representative cross-section of adults who live in the United States. For the first decade after World War II—a decade characterized by rampant racial discrimination in education, employment, and housing—a plurality of respondents never once identified such problems as the country’s most important.

That changed in 1956, following the Montgomery bus boycott. It changed even more dramatically in the mid-1960s, after the Birmingham and the Selma campaigns. Between 1963 and 1965, respondents to Gallup’s “most important problem” question consistently answered “civil rights” or “the racial problem.” The highest spikes came just after the actions in Birmingham and Selma.

In May and June 2020, more respondents gave race-related answers than had since July 1968. In other words, in the present moment, many Americans—including many White Americans—are paying attention to police violence and to other forms of structural racial injustice in ways that they have not for more than half a century.

But the change did not last. Between the late 1960s and the fall of 2014, respondents to the Gallup poll said that “racial problems” were among America’s most important problems only once: in May of 1992, following the riots in Los Angeles after the acquittal of the White police officers who brutally beat Rodney King.

Then, starting in the fall of 2014, the Movement for Black Lives put racism back on the American political agenda. December 2014 was the first time since the 1960s that a plurality of Gallup’s respondents identified as America’s most important problem one related to race or racism. In May and June 2020, more respondents gave race-related answers than had since July 1968. In other words, in the present moment, many Americans—including many White Americans—are paying attention to police violence and to other forms of structural racial injustice in ways that they have not for more than half a century.

Of course, Black Lives Matter protests are unlikely to persuade committed racists to change their views. Yet commentators who question the effectiveness of sit-ins, die-ins, highway shut-downs, and other forms of disruptive politics on the grounds that they fail to “change hearts and minds” miss the point. Political disruption can compel people who, in principle, reject racial inequality to pay attention to the realities of structural racism. In so doing it can change the terms of political discourse.

In the summer of 2020, many White Americans turned their attention to structural racial injustice for the very first time in their lives. And at least some of those White Americans began to grasp racism’s magnitude and to grapple with their responsibility to help to change it. That would not have happened if not for the democratic work of their fellow citizens: the activists who disrupted them, commanded their attention, and showed them what democracy looks like.

Editor’s Note: An edited version of this essay appeared in the November 2020 issue of Washington University magazine.