War comics, with a democratic twist, seem to be coming of age … again. The Lincoln Brigade is a good if imperfect contribution.

Art about warfare goes back to Francisco Goya and far beyond, but the original comic book craze famously kicked off the comics careers of two future industry giants: Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. Boy Commandos (1942), a huge hit ushering in the big boom of war comics, featured youthful partisans from across Europe and the United States in common cause against the fascist menace. That GIs overseas themselves constituted a large chunk of comics buyers did not, however, much alter the stereotype of blonde heroes in most of the hugely popular war comics to follow. Nor fend off the stereotypes of exotic temptresses (notably Asian) and clueless dark-skinned natives in the comics and newspaper strips from the 1930s, continuing through the Cold War era to follow.

Several lines of EC comics, mostly 1950-53, some of them edited and drawn in part by Mad founder Harvey Kurtzman, marked only a temporary change. But as a respite, it was astonishing: “Comics realism,” stories literally taken from life and especially from the Korean War (GIs back home and writing letters to Kurtzman shaped his plots), with horror scenes of carnage and civilians trapped hopelessly between the warring sides. Outside of EC, the comic book myth of the spotless American Warrior-Crusader never really went away, and after EC’s glory years, complicating war narratives tended to disappear almost entirely.

The Spanish Civil War emerged as a grand subject in the small but dynamic comics industry of post-Franco Spain some forty years ago.

All that seems long ago, so long that only scholars of the field are likely to recall the comic books late in the Vietnam War that seemed, on a page here and there, more regretful than heroic. Further decades pass. Then Joe Sacco arrived: a phenomenon of war-in-comics, a combination of reportage, personal and often ironic reflection that won readers across the world. Arguably, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, inventing or validating comics as an art, had prepared the way, at first and inevitably in the world of alternative comics far from the mainstream. Few would remember that Jack Jaxon (on violent Texas history) and Spain Rodriguez (on a range of military conflicts) had been offering artistic interpretations of armed conflict both highly personal and daringly realistic since the Underground Comix explosion of the 1970s.

The Spanish Civil War emerged as a grand subject in the small but dynamic comics industry of post-Franco Spain some forty years ago. Carlos Giménez, one of the children who survived the murder of their parents and grew up in the worst of prison-like settings, offered up the masterpiece Paracuellos in 1981, translated by Sonya Jones for U.S. audiences only decades later in 2016, with an introductory note by the legendary Will Eisner. Miguel Angelo Gallardo’s Un Largo Silencio (The Long Silence) a realistic depiction of a father’s survival through political quiescence, could be paired with Antonio Altarriba’s El Arte de Volar (The Art of Flying), regarded as the “Spanish Maus” of documented suffering. Among these, Los Surcos del Azar (Twists of Fate), by Paco Roca, might be the classic of armed antifascists, although it depicts survivors who escaped to fight the Nazis in occupied France.

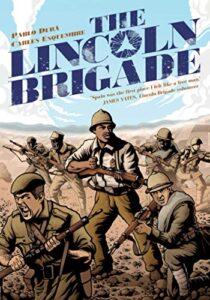

Even in this somewhat crowded field, The Lincoln Brigade is something new. Writer Pablo Dura, a veteran of mainstream Marvel comics, recalls on the book’s final page that he had the idea for this comic long ago, but only a few years ago managed to find the artist and publisher to bring the idea to life (or print). Carlos Esaquembre, an artist working in Spain, can look back upon his Lorca: Un poeta en Nueva York as a tribute to the antifascist culture. Together (and with an able colorist), they offer an action-packed narrative.

The Lincoln Brigade, it should be noted, is offered up by a comics company with no apparent altruistic or even political concerns. Supernatural horror titles seem to be their standby and distributors might be mystified, looking for more of the same in this comic. Not that it lacks horrors of the realistic kind.

Notably, the central figure in the comic, never much absent, is Oliver Law, the sui generis African-American commander of the Lincoln Battalion. The U.S. affiliate of the international project to save the Spanish Republic from the clutches of Francisco Franco generated enormous controversy in the second half of the 1930s, in part because for many, it was joined with struggles against racism. Even in defeat, the Battalion seemed to anticipate the antifascism of wartime and the “Double V” campaign to defeat racism back at home in the United States.

Even in this somewhat crowded field, The Lincoln Brigade is something new. Writer Pablo Dura, a veteran of mainstream Marvel comics, recalls on the book’s final page that he had the idea for this comic long ago, but only a few years ago managed to find the artist and publisher to bring the idea to life (or print).

In the opening pages, Law is a kid in Chicago, in 1930, where he meets the dynamic communist personality, Harry Haywood. In real history outside this comic, Haywood was also a notable Black Nationalist, expelled and recalled to the Communist Party in different periods, and author of a unique black-left memoir, Black Bolshevik: Autobiography of an Afro-American Community (1978). During the 1930s, Haywood more nearly exemplified the slogan “Black and White, Unite and Fight,” and he serves in the comic as an exemplar to young Oliver Law. Racist violence by Chicago cops hammers home the lessons to the bright and dedicated lad, who sets himself on changing the world.

By 1937, Law sneaks into France, disguised as a tourist. He crosses the Alps on foot and joins other men from a dozen countries, training together in a temporarily safe Spanish district. And he finds allies, like the fellow Brigadier, son of a White Congregationalist minister in Indiana, with a memory of a nearby KKK lynching that changed this teenager’s life.

The Americans, like their several thousand comrades, are ready to die but ill-equipped and also untrained for combat. Here, Law emerges as a potential leader, as tough as nails and bold enough to challenge the leadership that seems, perhaps influenced by Russian propaganda, to be deluded about the devastating outcome of battles lost to the trained forces of fascism. Equipped with the best military hardware of the time, defended by German-built planes (the antifascists have none), the fascists can be held off, but only held off, with heroic and self-sacrificial action. Franco’s forces cannot be defeated. Woody Guthrie famously wrote, or rather expanded with his own verses, the saga of the battles in the Jarama Valley, sung to the tune of “The Red River Valley,” as a parting salute of the surviving heroes returning to the United States.

Critics will note a lot missing here. Ruthless attacks by Loyalist forces on the Spanish anarchists did not actually involve the Americans but tainted, for many, the heroism of the Lincolns’ efforts. George Orwell and others seemed to raise the highly improbable prospect that any force, more democratically organized, could have defeated Franco. Given the support that the fascists received from the Germans and Italians, this was most unlikely. A firmly anti-fascist U.S. government might have made a decisive difference, a possibility alluded to in The Lincoln Brigade. The American unwillingness to get involved in European conflicts—a reluctance born of a bitter recollection of government promises and lies in the First World War—coincided with the ferocious Catholic support of Franco. Help was not coming.

On another and smaller note, we see an American woman photographer cryptically called “Gerda,” on the scene in several pages of the comic. We never learn that she was the very real Martha Gellhorn, a heroine in a half-dozen different ways, along with her lover, Ernest Hemingway, who seems to slip by with a mention and a few panels. Understandably, the comic is not really about these visitors.

Critics will note a lot missing here. Ruthless attacks by Loyalist forces on the Spanish anarchists did not actually involve the Americans but tainted, for many, the heroism of the Lincolns’ efforts.

Much of The Lincoln Brigade involves actual warfare, action scenes that have little to do with the heroism of Boy Commandos but a lot to do with the grimness of EC war comics. Blood flows. Victories are followed by defeats, and by the end of the comic, we approach the present with old men’s memories. Franco is dead at last, and the Lincolns’ survivors can revisit Spain with a small sense of triumph. An afterword is brief—we could have wished for more—but it usefully references the Veterans of the American Lincoln Brigade (VALB) becoming today’s American Lincoln Brigade Archive (ALBA), as “the Lincolns” themselves passed away.

The comic is a worthy effort, notwithstanding any shortcomings. We hope it will find its readers.