Robin DiAngelo is racist. In fact, all whites are racist. Yes, that even includes you, progressive and liberal whites. It is difficult to hear this because you think racists are bad people and you consider yourself a good person. But, it is precisely the difficulty you have hearing and recognizing the ways in which you perpetuate white supremacy that exposes your white fragility according to Diangelo.

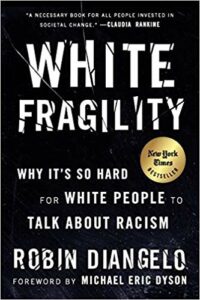

In White Fragility: Why it’s so Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, DiAngelo carries her white audience through the above logic. (She is explicit at the outset that she is writing primarily for a white audience). DiAngelo covers historical origins of race and whiteness and how the concepts were legally defined precisely to maintain the racial status hierarchy in which whites are dominant and people of color are subordinate. Although whiteness has ostensibly become invisible to most whites (in that many deny the ways in which race structures their perspectives), it shapes the lives of everyone in society: their histories, worldviews, behavior, everything, in a way that perpetuates white dominance.

Without providing the historical and social context she does, this information might feel abrupt or harsh. But DiAngelo gently guides the reader to this understanding using anecdotes from anti-racism workshops she has led and from her own experiences. She starts out assuming the reader has no framework for understanding the racial reality of the United States. She outlines common assumptions about race and then debunks those assumptions.

DiAngelo argues that intentions do not matter as much as the hurt they cause. Defensiveness detracts from anti-racist efforts.

DiAngelo argues whites are racist because they are steeped in a racist culture. The United States has supported pervasive racial inequality from its inception. Since its beginning, “the US economy was based on the abduction and enslavement of African people, the displacement and genocide of Indigenous people, and the annexation of Mexican lands …” (15-16). DiAngelo reviews history suggesting that race was used to help define the social hierarchy and to legitimize and justify the subjugation of people of color. In fact, she informs the reader, the very concept of whiteness was introduced in colonial law to legally define privilege and exclusion (e.g., only those legally defined as white were allowed citizenship). In other words, the very concept of race is one that privileges whites over other groups. By virtue of being socialized with this reality, whites become racist—it is an inevitable result of growing up in a racist society. DiAngelo does not entertain either biological or cognitive arguments for the existence of racism (but those arguments do exist).

Importantly DiAngelo distinguishes between racism and prejudice. Prejudice is defined as negative attitudes towards a group based on group membership, and says that “all humans have prejudice” (19). In contrast, racism is a form of oppression that is “backed by legal authority and institutional control… the default of the society [that is] reproduced automatically. Racism is a system” (21). Because of the structural and power component of racism, whites are racist but people of color cannot be; the latter do not have the power or history to be racist.

One of the more pernicious assumptions whites make is that racists are bad people and hence that good people cannot be racist. The fundamental problem with believing that good people cannot be racist is that people who consider themselves moral have difficulty recognizing when they have committed a racist act. If their bias is pointed out, they often become defensive. They may try to explain what they really meant, or what their intentions were—rather than focusing on the particular problematic behavior or the racist system that gave rise to the behavior. DiAngelo argues that intentions do not matter as much as the hurt they cause. Defensiveness detracts from anti-racist efforts. If someone points out that a behavior is racist and a white person takes offense or cries (there is a whole chapter dedicated to white women’s tears), the attention shifts to the perpetrator’s feelings rather than the actual victim in the context.

White Fragility may be difficult for some readers to get through because it provides perspectives that are in sharp contrast to their own understandings of themselves.

DiAngelo contents that racism lies on a spectrum. Good people can, and do, commit racist acts—often without realizing it. She provides multiple examples of how even she, whose work is dedicated to fighting racism, also engages in behaviors that harm people of color. These anecdotes help the white reader recognize that no white person is immune. But just because everyone does it, does not mean you are off the hook. White Fragility may be difficult for some readers to get through because it provides perspectives that are in sharp contrast to their own understandings of themselves. Nonetheless, it is important to remember that “Racism hurts (even kills) people of color 24-7. Interrupting it is more important than [white people’s] feelings, ego, or self-image” (143).

Given that the book was written for a white audience, how did I feel as a person of color reading it? The simple answer is mixed. Diangelo identifies many pet peeves that often surface in interracial interactions (e.g., an assumption that people of color can or should work through whites’ racial discomfort with them).

That said, there were many times she could have pushed further to challenge herself and the reader more. In what I initially considered to be a very astute point, DiAngelo asks her reader to question the way history is taught to emphasize meritocracy and individualism and obscure systemic racism. She wonders how our understanding of power structures would be different if historical events were worded in a way to emphasize structural racism. For example, rather than focusing on the ways in which Jackie Robinson was an incredible baseball player who was able to break the color line, what if instead we were taught that Jackie Robinson was “the first black man whites allowed to play major-league baseball”? (26) The second description highlights the way in which whites controlled Robinson’s opportunities. The wording also removes judgment about those who are less successful. I applauded this point, but I was disappointed when just a few pages later, DiAngelo falls into familiar patterns in describing school desegregation. She notes that Ruby Bridges was “the first African American child to integrate an all-white elementary school …” (28), rather than describing her as the first child allowed by whites to integrate.

I recognize DiAngelo’s humanity and want to afford her space to make mistakes, but it is also an exhausting reminder of the work ahead when even the person pointing out this issue can herself succumb to it in a matter of pages. Perhaps this humanity is what may allow a white audience to connect more easily to her and, thus, be more willing to accept her argument.

I had the added layer of reading White Fragility as an academic who studies prejudice and stereotyping with a particular interest in whites’ perceptions of threat. DiAngelo touches on many relevant social psychological concepts (e.g., aversive racism, implicit bias, competitive victimhood). She leaves out jargon and writes with an engaging, conversational tone suitable for a lay audience. But as a scholar, there were also moments of imprecision that irked me. Prejudice and stereotyping are not synonyms—even though that is unclear from her writing; the former is a component of attitudes based on emotions (e.g., dislike) and the latter is based on cognition (or thoughts). She does do a good job illuminating the distinction between prejudice and racism, which is perhaps more important for her central arguments.

What was most difficult for me as an academic were moments when her perspective contradicted empirical evidence. For example, DiAngelo argues that some people of color, including Obama, have made it into circles of power because “they support the status quo and do not challenge racism in any way significant enough to be threatening.” (27) My own work directly challenges that assertion. Obama may be less threatening than other African Americans, but he was perceived of as threatening when he was in power. When my colleagues and I encouraged whites to consider racial progress and Obama’s presidency, as part of a research study, they demonstrated evidence of threat. Specifically, whites had lower implicit self-worth relative to baseline (whites implicitly felt worse about themselves). Our research also demonstrated that they felt better about themselves to the extent to which they blamed a negative event on racism against whites. In other words, whites were threatened by Obama. In fact, they seem to be threatened by any perceived changes to the status quo that might challenge their dominance: including increasing demographic diversity.

DiAngelo provides a solid basis for understanding whites’ reluctance to talk about race—particularly for a lay audience, but it comes up a bit short for an academic one.

White Fragility also lacked a discussion about concrete resources that are diverted from people of color when whites are threatened. DiAngelo notes that white people’s hurt (in response to being alerted about their racism) diverts attention from the real victims. Attention is important, but real resources are perhaps more important. Threat increases the extent to which whites perceive that their group experiences racial discrimination. Perceptions of bias against whites, in turn, lead to attitudes and behaviors that can literally affect the distribution of concrete (not just attentional) resources. When whites believe they are victims of discrimination, they do not simply withdraw; they actually endorse policies that are more likely to favor whites and hurt people of color.

In sum, DiAngelo provides a solid basis for understanding whites’ reluctance to talk about race—particularly for a lay audience, but it comes up a bit short for an academic one. I believe this book could serve as a helpful guide for whites wanting to engage in authentic relationships with people of color. It is thought-provoking, insightful and refreshing in its directness. So, in the spirit of that directness, I end with this:

If you are white, you are racist. But do not get caught up feeling devastated about this fact. The sooner you recognize this and let go, the sooner you can work toward dismantling systems of oppression.