A measure of our times

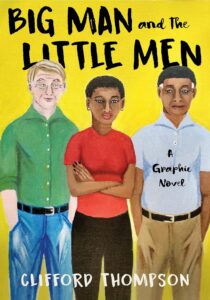

The morning after the 2016 U.S. presidential election results were called, I found myself frozen in fear, unable to bring myself to speak or move, not comprehending how what seemed implausible had become possible. I would feel the same way many times over in the next seven years watching both the United States and my home country India rapidly and furiously erode the rights of every marginalized community. Reading Clifford Thompson’s graphic novel Big Man and the Little Men quickly immersed me in a fictional world that could just as easily be the U.S. presidential election landscapes of 2016, 2020, and maybe even 2024.

Big Man and the Little Men begins on the campaign trail. The story follows essayist April Wells on an unusual (for her) writing assignment: covering the campaign of presumptive presidential Democratic nominee Bill Waters. Although she frequently wonders why she was chosen for the job, she leans into understanding Waters and his politics. “Strength through Unity!” says his campaign bus, in stark contrast to his Republican opponent Lee Newsome’s fascist rhetoric. However, April finds her instincts about Waters are derailed when a sexual assault allegation against him surfaces. Her investigation into the accusation yields more questions than answers; April’s editor goes missing and the FBI gets involved. Paranoid and not knowing who to trust anymore, she seeks out her childhood friend Samuel Benjamin, who is now the mayor of the “large town, small city” they both grew up in. Samuel and his friends help April unpack what turns out to be a larger political conspiracy. Big Man and the Little Men throws us into an election campaign that unfolds and unravels in front of us, making us pay close attention to how information can influence ideologies and beliefs.

A lot of what Big Man and the Little Men wants us to grapple with comes through what its characters say. Waters sets the tone when he first says, “Think of America as an ongoing story. What makes a story work? Knowing what the characters want. We are all characters in America.” (8) Each of Thompson’s characters pose or grapple with contradictions. Compared to Newsome, Waters is objectively the less dangerous choice, but his reputation is disadvantaged by rumors of affairs with male staffers. When April learns of a sexual assault allegation against Waters, she is torn between her beliefs (that she trusts a survivor) and the political reality (that this news would ensure Newsome’s win). Sam has to reconcile his past with his future and ambitions. As readers, we share the collective burden of everyone’s actions and their implications. When Waters says “We respond not to what’s in front of us, but to what we’re already thinking” (61), he speaks directly to the readers and how we react to what we see and read on each page of this book. We too are characters in America, and in this story.

Big Man and the Little Men throws us into an election campaign that unfolds and unravels in front of us, making us pay close attention to how information can influence ideologies and beliefs.

Clifford Thompson’s previous nonfiction book, What It Is: Race, Family, and One Thinking Black Man’s Blues (2019) published by Other Press, is a reflection on nation and identity in response to Donald Trump being elected as president. With Big Man and the Little Men, he brings together these ideas and his background as a visual artist into a fictional graphic novel about politics in the United States. Thompson notes in the book’s acknowledgements that the form of the graphic novel was one way for him to “make a film” (without actually making a film). Even without this context, Big Man and the Little Men’s cinematic narration and episodic structure is evident. Hand-lettered chapter title pages echo title cards in Quentin Tarantino’s films. Narration text has the distinct quality of a voiceover. The narrative moves between different places and cuts back and forth in time in unexpected yet effective ways. In perhaps a self-aware nod to this, one character says to another, “Kind of like a Tarantino movie, but without the blood.” (53)

The “graphic” in graphic novel

The form and grammar of a film, however, are different from that of a comic. One of those critical differences is time. Films are linear–and rapid–sequences of images. While comics are also sequences of images that are meant to be read linearly, they can (and do) break linearity. In his book Understanding Comics (1993), when Scott McCloud attempts to distinguish between film and comic as a set of sequential images, he describes juxtaposition as a key differentiator. (8) What happens when one panel sits next to another on a page? McCloud also describes six ways that passage of time is constructed in comics for readers to experience a narrative continuity, or closure. (67) By incrementally jumping time and space, each of these transition types increase the amount of narrative closure a reader is pushed to achieve. Another difference between comics and film, that also impacts our understanding of time, is that comics require us to perform two different activities simultaneously and quickly: to read words and to see drawings.

Time, in Big Man and the Little Men, is slow, sometimes unmoving. Many portions of the book employ what McCloud calls “moment to moment time transitions.”1 We see the same subjects across panels that show change over small increments of time. Our passage of time in this book then relies heavily on the text in speech bubbles and not through what the illustrations show us. In film, this treatment is reminiscent of single-camera scenes which are successful when actors communicate through non-verbal cues in addition to dialog. In most of Big Man and the Little Men’s pages, the result is a lot of static panels that could benefit from different visual choices. Thompson’s organization of the narrative into panels is like a storyboard for a film adapted into the framework of a comic.

This slowness of time works in instances. The campaign bus panels are always composed the same way, the bus in the center of each panel seemingly stationary while the landscape around it changes. These panels reflect the nature of time in electoral politics–the campaign is long and always on. Similarly, a six-panel sequence of April writing, where she only sits down to type in the third panel, pacing around in the remaining panels, captures how time seems to pass during the writing process (this page came to my mind many times as I typed this review). Pages that show April watching Newsome’s TV appearances suspend us in time, trapping us in his hateful speech. Newsome is shown only briefly in two panels in a TV appearance, but his very Trumpian voice is embodied as speech bubbles coming through TV screens, the impact of his words reflected directly in April’s body frozen in frustration, anger, and pain.

Thompson’s organization of the narrative into panels is like a storyboard for a film adapted into the framework of a comic. This slowness of time works in instances.

Two panels in the book interrupt its overall panel treatment in such an arresting way I found myself craving more of that. On pages 33 and 64 each we see a single panel of April in the shower, her back to the readers, contemplating problems at hand. Time passes within these two panels: waterfalls, water splashes, water steams, April’s thought bubbles cloud around her, all simultaneously and continuously. Both these panels seize something only the comic medium can do: make minutes and hours pass in a single image.

Big Man and the Little Men could have engaged the form of comics in more ways that fully embrace the tensions and potentials of putting words and images together in sequence. The story develops through dialogue, often through extended talking-head panel sequences, like Waters describing his politics and his understanding of the country and its people. The Poirot-esque whodunnit–and whydunnit–reveal takes place too quickly in a single, text-heavy half-page panel, where April lays everything out.

The book closes with Waters’ campaign bus, appearing for the first time in three dimensions, moving on the road. A puff of exhaust smoke trails the bus as it moves down the road, across the page, returning us back into the book. Big Man and the Little Men is less about the destination of the election result and more about the journey—what we can learn about people’s relationships, motivations, opinions, and beliefs.