1. The foreground

On Tuesday, August 6, voters in Missouri’s 1st Congressional District will decide who will be the Democratic nominee, and hence the winner of the seat as the district is deeply Democratic: either incumbent Cori Bush or challenger Wesley Bell, currently the St. Louis County prosecutor. But both Bell and Bush are products of the insurgency politics that resulted from the 2014 Ferguson uprising, the populist response to the police killing of Black teenager Michael Brown. That these two should wind up running against each other seems an odd outcome of an attempt to increase the number of non-conformist, leftist politicians in an increasingly conservative-run state. In this case, the best result for those on the left would be a Bush victory which would keep the balance at status quo ante. A Bush loss would reduce the radicals’ team by one, which would not benefit the cause as it would mean, in effect, another start-up to replace or restore her voice somewhere in a significant elected office.

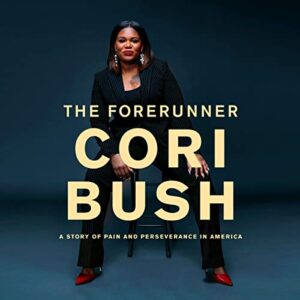

Bell had originally planned his political ascension as a challenge for Republican Josh Hawley’s US Senate seat. After the October 7, 2023, Hamas attack against Israel, this plan changed as Bell abandoned his quest against Hawley, a steep climb for a liberal Black St. Louis politician to win a state-wide seat, to offer a primary challenge for Bush’s congressional seat. He made this move before the end of October. One of Bell’s biggest backers has been the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), which has targeted elected officials who have been, by their lights, too pro-Hamas and too pro-Palestinians since the outbreak of the latest Mideast hostilities. Many St. Louis Jews consider Bush’s charge of “genocide” against Israel and her opposition to a congressional resolution condemning Hamas infuriating. Bush is a redoubtable or notorious (take your pick depending on your politics) member of the Squad, the group made up of the most radical or leftist congressional representatives, all Democrats, people of color, and mostly women. AIPAC has already successfully primaried Squad member Jamaal Bowman of New York City for the same reason that Bush has been targeted: too sympathetic to Hamas, too chummy with the BDS (Boycott, Divest, and Sanction) Movement, and too prone to saying things about Jews that many Jews, reasonably, may not much like. In this little political drama, Bell has become the establishment candidate (and, thus, a sellout in the radicals’ view), and Bush remains, as her autobiography, The Forerunner, makes clear about her political career, the rebel, the woman who cannot be bought. Politics, just like melodrama and sports, needs a good guy and a bad guy in a showdown. It is the closest thing we have to a western.

August 6 is the Transfiguration of Jesus Day. Cori Bush, who attended primary and secondary St. Louis Catholic schools and who is a Protestant minister and faith healer, surely knows this, so the day of her political fate will have even deeper meaning for her.

It is not surprising that Bush feels considerable empathy for Palestinians and their cause. Left-leaning Blacks have felt this way since at least the late 1960s. As she mentions in The Forerunner, she grew to know some of them as they supported the 2014 Ferguson uprising, where Bush became a public figure: “Our conversations about the oppression they and their family members experienced opened my eyes. I saw that so much of the militarized state violence we face as Black people in the United States is similar to what Palestinians face from Israel.” (180) More than any previous racial uprising in the United States in the last sixty years, there was much talk among the demonstrators and protesters about solidarity with the Palestinians. We Black people are the Palestinians of the United States; the Palestinians are the Black people of the Middle East. This attitude, doubtless aided and abetted by social media, would only intensify with the 2020 George Floyd uprising for which Ferguson served as a kind of dress rehearsal. Both the Ferguson and George Floyd uprisings might be considered something like America’s versions of intifada. This kind of identification between Blacks and Palestinians among the younger generations would certainly trump any sort of “special relationship” between Blacks and Jews that may have existed among older generations. Put another way: older Blacks may have identified with the enslaved Hebrews in their fight against Pharoah; younger Blacks are more apt to identify with Ancient Egyptians as a superior African race who invented civilization. The Black Americans’ relationship to an Islamic, “colored” world in the Mideast is more complex than many might suspect.

It is impossible to say who will win this primary as polling results differ widely. On June 25, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch endorsed Bell, saying Bush “has generally appeared less interested in working [the] system for the good of her constituents than attacking it on behalf of a small, hard-left klatch of lawmakers—‘the Squad’—who are good at getting headlines but bad at actually accomplishing anything.” The editorial does not specify exactly what Bush was supposed to have accomplished during her tenure. It does condemn her for voting against Biden’s “landmark infrastructure bill.” Bush offers her defense here. She votes against her party a bit higher than average and maybe that is another reason the establishment decided to primary her.

Bell and Bush are sufficiently experienced and skilled politicians, so it is not wise to sell either of them short, although realistically Bell is favored. In the Catholic, Anglican, and Orthodox churches, August 6 is the Transfiguration of Jesus Day. Cori Bush, who attended primary and secondary St. Louis Catholic schools and who is a Protestant minister and faith healer, surely knows this, so the day of her political fate will have even deeper meaning for her.

2. The background

An autobiography is not just a story, it is a strategy of how the autobiographer can construct a coherent self, can blend self-contradictions, can make the reader believe, not just the events of the life, but the meaning the autobiographer imparts to the life. “How did I get to be what I am?” an autobiographer on the surface seems to ask. “And how can I make you believe that what I say I am and how I claim to have gotten there is important to you, dear reader?” The latter is the autobiographer’s true mission.

Bush writes: “This is not your typical political memoir. I have no problem challenging our notions of what is proper or what is respectable. I have no problem being vulnerable and sharing episodes from my life that might make some readers uncomfortable.” (xvii) But this bow to honesty in what is being presented as a kind of “rogue” political memoir is the autobiographer’s trick to convince the reader that the writer is sincere. Sincerity is what an autobiography sells. And Black autobiographies are especially inclined to promote their sincerity as they are usually stories of redemption: from slavery to freedom, from godlessness to faith, from self-concern to activism and selfless mission. These are transfigurations, as the old slave narratives of the Victorian era used to read, “From the darkness to the light.” The Forerunner is no exception to that rule. There is nothing underhanded in any of this strategic posturing or literary self-creation. It is simply the Black autobiographer acknowledging the tradition of the genre as it has worked for Blacks. It was Malcolm X, the most famous of all Black autobiographers, who said, “I want to be remembered as someone who was sincere.”

Even if one knew nothing more about Cori Bush than what one reads in newspapers, one would have to concede that she is a remarkable woman whether or not one liked her or her political positions. Here is a woman who could have, at several points in her life, submitted to her condition, to her circumstances and gone no further. But she has a considerable will and a belief that she is more than her circumstances at any given moment. She overcame two abortions and two rapes by the time she was in her early twenties; she survived abusive boyfriends who beat her and who had babies with other women they called “baby mamas”; she endured a terrible marriage with a man who had five other children, was habitually unfaithful, and paid no child support for the two children he had with Bush, who endured extremely difficult pregnancies. The only stable relationship she has with a man is with her father, about whom she writes a great deal more than her mother, who is positively written about too. Errol Bush, a union meat cutter, was always political, having been both an alderman and mayor of the city of Northwoods.

Sincerity is what an autobiography sells. And Black autobiographies are especially inclined to promote their sincerity as they are usually stories of redemption: from slavery to freedom, from godlessness to faith, from self-concern to activism and selfless mission.

If this book’s subtext might be simply stated it is the story of a daughter’s relationship with her father. He is the Black man that the other Black men in her life fail to be, unfailing when she needs financial support to attend college, when she needs to escape her brutal boyfriends and husband, when she needs someone to take care of her kids in a pinch when she becomes an activist. The person she is most worried about disappointing is her father. Her father taught her Black history, the traditions of Kwanzaa, and took her from Ascension Catholic School to Cardinal Ritter College Prep when she felt undermined by the racism she experienced at Ascension. When she announced her first campaign against Lacy Clay in 2018, her father was there: “My dad introduced me and then stayed onstage, next to me, as I gave my remarks.” (215)

Bush’s campaign against Bell will be her fifth. As a result of her Ferguson activism with Frontline Ferguson, she was encouraged to enter the Democratic primary for the US Senate against Jason Kander, though terribly inexperienced and abysmally underfinanced. She garnered a bit more than thirteen percent of the vote.

(Four weeks after her loss, she was raped by a faith healer who was showing her a property to rent. Her assailant convinced the court that it was consensual sex. She was bitter about the cops, the handling of the rape kit, and the less-than-vigorous prosecution. Sometimes incarceration is a sound form of justice, even to a leftist.)

She lost by twenty points to Lacy Clay, scion of the legendary Black St. Louis politician Bill Clay, in 2018 in her first run for the 1st District Congressional seat. She came into her own as both a mature candidate with proper support and a disciplined message in 2020 when she beat Clay by three percentage points. She handily beat Steve Roberts in 2022 by over forty points to retain the seat. Her opponents realized that it would take someone with more political heft than Roberts to beat her, hence Wesley Bell.

The most striking contradiction that Bush manages to resolve is that of science and religion. Through considerable effort, Bush became a registered nurse, and seemed to have succeeded at it despite the racist attitudes of some White nurses and as well as some White patients. She also became a minister, not trained in a seminary, starting her own church. As she experienced as a young girl with random Black men on the street, she found the Black men in the church to be sexual predators and players who treated the women as if they were in a harem. She merged these two professions by becoming a faith healer, at one point, in 2011, traveling around St. Louis offering to heal people, a skill she truly believed that she had. This dovetailed nicely with her sense of social message, as, like Jesus, she healed people for free. Of course, one is forced to ask: what is the difference between miracles and magic? At any rate, you cannot beat healthcare at that price!

Even if one knew nothing more about Cori Bush than what one reads in newspapers, one would have to concede that she is a remarkable woman whether or not one liked her or her political positions. Here is a woman who could have, at several points in her life, submitted to her condition, to her circumstances and gone no further.

The faith healing, her past life of evictions, sexual victimization, homelessness, varied low-level employment, divorce, and the new-style political resistance of Ferguson gave her a great deal of street cred and authenticity with many of the people she claimed to speak for and represent but it made her anathema to bourgeois Blacks, the Black elite, the civil rights Black establishment that saw her as possessing all the traits of the Black parvenu, the gatecrasher, an unsophisticated religious zealot who spent a good deal of her life doing low-wage work. And old guard Black people asked, “Why don’t you take care of your kids instead of wanting to unseat Black men like Lacy Clay!” She speaks of this constantly in the book where, indeed, her complaints against the Black establishment are nearly as vehement as her complaints against racism, sexism, inequality, and the like. Alas, those pedestrian-minded Blacks who do not perceive the power of transfiguration when it is right in front of them!

The Forerunner is one of the more important autobiographies written by a St. Louisan. It ought to be read by Democrats, Republicans, and all third-party members. It takes a bit of skill to merge leftist politics, old-time Black evangelical Protestantism, and the supporting craft of nursing into something coherent.