Once I wheedled a friend and her twin sister into listing the top-five annoying questions people asked them. Number one was quickly agreed upon: “When one of you experiences pain or sadness, does the other feel it too?” Intrusive and tiresome to twins’ ears, the question nonetheless manifests a genuine philosophical concern about the limits of identity and sentience. If ordinary twins are irked by it, one can only imagine the intensity with which this and related queries circumscribe the lives of conjoined twins. As sharers of the same body, can conjoined twins feel for each other? Do they communicate telepathically? And, if so, are they one or two? Where does one end and the other begin? What do they share and what is individually demarcated?

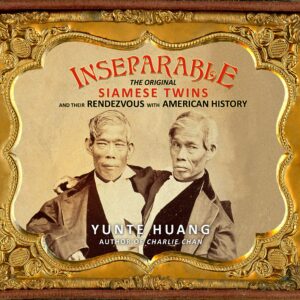

Yunte Huang leaves these questions unanswered in his new biography of Chang and Eng Bunker (1811-1874), the celebrities (celebrity?) popularly known as the “Original Siamese Twins.” Huang’s is a counterintuitive and—dare I say—welcomed gesture. The excitement in his book does not derive from a tentative solution to the conundrum of twins’ individuation, but from how this riddle traverses endless clinical reports, phrenological exams, promotional materials, legal documents, humorous sketches, newspaper advertisements, and popular invective. Such a vast and multidisciplinary archive evinces that, as medical and racial Others, Chang and Eng pushed nineteenth-century taxonomies, straddling the line between human and inhuman, normal and abnormal, slave and master, one and many. For Huang, the most fascinating thing about Chang and Eng was Americans’ fascination with them.

The excitement in [Huang’s] book does not derive from a tentative solution to the conundrum of twins’ individuation, but from how this riddle traverses endless clinical reports, phrenological exams, promotional materials, legal documents, humorous sketches, newspaper advertisements, and popular invective.

Given the depth and width of Huang’s historical excavation, Inseparable emerges as an ideal companion to Cynthia Wu’s Chang and Eng Reconnected (2012)—and, yes, the irony of pairing up books on Chang and Eng does not escape me. Whereas Wu centers on the Twins’ numerous descendants, tackling their cultural memory and interracial genealogies, Huang returns the focus to the Twins’ there-and-thens. Readers will get the impression that Chang and Eng lived multiple lives. Imported from a placid, river-merchant life in Siam, they would reach unexpected fame in England and the United States. After retiring from the stage, they turned cotton planters in North Carolina, married two (non-conjoined) sisters, and fathered twenty-one children, plus at least one illegitimate child with one of their black slaves. ¹

Huang threads these strands into a coherent narrative about how audiences of many extractions grappled with the Twins’ incoherent body. Political theorists relied on them to explore notions of self-sovereignty and popular representation; preachers polemicized about the nature of their soul(s); penny-press hacks circulated juicy details of the Twins’ married life; household writer Mark Twain, among others, was not indifferent to the Twins’ potential as a national metaphor. Above all, an army of doctors, anatomicians, physiologists, and hucksters wrote rivers of ink claiming to have reached final word on their extraordinary bodies. In fact, part of the Chang and Eng craze had to do with their “extraordinary health” and eventual longevity (40), as if their organism proved all the more aberrant by the fact that, in the end, it functioned quite well. Relatedly, their impeccable manners and penchant for wit also caught off guard those spectators expecting a sub-human, antipodal monster.

Even though they were not the first conjoined twins exhibited on US soil, Chang and Eng widened the horizons of the freak show, adding a layer of sophistication and orientalism to a spectacle that had revolved mostly around revulsion and fear. The Twins paved the way for a host of refined freaks—the cherubic dwarf General Tom Thumb, for instance—who incarnated normative and national values rather than their opposites. If sideshows had hinged mostly on the monstrous Otherness of what-is-its, bearded ladies, and microcephalics, with Thumb and the “Siamese Double Boys” (53) this mass-entertainment ritual also started to fashion hyper-citizen figures. Chang and Eng’s corporeal uniqueness did not prevent many Americans for seeing in them an idealized image of themselves. Their odd anatomy and Chinese ethnicity notwithstanding, the Twins enchanted audiences as exemplar citizen-subjects who upheld a peaceful co-existence with each other. Huang describes a “strategy of alternate mastery” (233) according to which each twin took turns as decision-maker and leader of the two. In one of the book’s most delightful ironies, we learn that it was the Twins’ wives who eventually parted ways after a big dispute, forcing Chang and Eng to spend “three days at each home and each conjugal bed—a rigid routine they would follow religiously till their last breath” (248).

But Chang and Eng’s lifelong entente was also something to resent in a rapidly changing background that comprised fierce Jacksonian individualism, the traumatic split of Secession, and the imperfect Reconstruction that ensued. The Twins simultaneously embodied Jeffersonian republicanism, with its emphasis on horizontal community-making and even distribution of power, as well as a capitalist ethos that prioritized competition and growth. If American democracy dreams of equal, exchangeable citizens, Chang and Eng’s alternate mastery drove the point home. However, as another astute observer of the Twins has argued, their relationship was more akin to an ever-shifting master-slave dialectic than to one of equality and sameness. ² All in all, the Twins were complex signifiers, and one of Huang’s biggest contributions is to unravel the ambivalent desires and fantasies Americans invested in their conjoinedness.

… part of the Chang and Eng craze had to do with their “extraordinary health” and eventual longevity, as if their organism proved all the more aberrant by the fact that, in the end, it functioned quite well. Relatedly, their impeccable manners and penchant for wit also caught off guard those spectators expecting a sub-human, antipodal monster.

On a non-figurative realm, though, the Twins always gave equivocal signs about whether they considered themselves a unity or a duo. In letters and other personal documents they alternate “I” and “we” pronouns (143). In their plantation ledgers, their capital appears inventoried on separate columns under each name, “with Eng possessing 300 acres of land and nineteen slaves,” and “Chang owning 425 acres and eleven slaves” (284). Their “Chang Eng” signature strikes us as a one man’s job. In the “Siamese_Twins” inscription right below, though, the low dash typographically reenacts their compulsory linkage (137).

Numerous medical experiments failed to shed definite light on the twins’ constitutive essence. These reports rightly take up the bulk of Inseparable, as they accompanied the Twins on every stage of their post-Siam careers until well after their death. In 1830 Dr. Peter Mark Roget applied moderate electrical discharges to the Twins in order to prove that their linked flesh constituted a single “galvanic circuit” (85). Conversely, another experiment traced the residue of an asparagus, which only Chang had eaten, in both the Twins’ urine, concluding that “the sanguineous communication between the united twins is very limited” (86). Conjoined twins were not blood brothers, as it turned out. As the list of auscultations, diagnoses, and experiments grows longer, Huang realizes that the debate over the Twins’ being one or two had started to unfold in circles: “As all these experiments and records showed, the twins were actually both—they constituted one inseparable unit, yet they were two unique individuals” (87). Once again, Huang is more interested in studying paradoxes than in solving them.

Inconclusive as they proved, scientific and pseudo-scientific accounts of the Twins instigated audiences’ mixed desires, desires that Huang does not always capture in full detail. For instance, although the author successfully charts that leap of the imagination by which audiences sublimated fears of national disunion via the twins’ united body, the reversal of this fantasy tends to fly under his radar. After all, did not showmen and audiences also crave the Twins’ separation? Was not their excision also construed as an easy, abrupt end to the philosophical, political, and scientific complications they personified? Ticket-buyers wanted to see Chang and Eng clash. On the one hand, manager Abel Coffin asked them to exhibit a high level of synchronicity in their performances, executing “somersaults in tandem” and “quick backflips” (82); on the other, the Twins’ repertoire often entailed some kind of competition, as the Twins vied in chess, badminton, shuttledore, and battledore (83). Given the harmonious compact the Twins had reached in their everyday life, it is as if jealous spectators secretly yearned for their separation. Huang does not acknowledge—yet provides enough evidence of—a surreptitious desire for their harmonious reciprocity to come undone as a mere façade. When eccentric socialite Sophonia Robinson wrote a poem declaring her romantic infatuation with the Twins, she voiced her frustration at their conjoinedness: “How happy I could be with either / Were the other dear charmer away” (89). Rumors of a tentative surgical separation were kept alive by interested parties such as entertainment mogul P.T. Barnum (69) and, if someone excelled at knowing what the common man wanted, that was Barnum.

With Americans’ contradictory stance towards the Twins in mind, the true protagonist of Inseparable becomes neither Chang nor Eng, but their connective tissue. This piece of flesh comprised “a mass two inches long at its upper edge, and about five at the lower” (qtd. in Huang 48). The Twins’ axis of symmetry, it had one navel in its exact center (78). Those who wished to see the Twins separated or, at least, in discord, surely loved to learn that, “over the years, constant tugging had stretched the cord from its original four inches in length to five and a half” (xxv). In the many posters and memorabilia compiled by Huang, illustrators are never afraid to depict—even foreground—their connective membrane (70). Poet Hannah F. Gould turned an eye to this “Mysterious tie by the Hand above, / Which nothing below must part!” (qtd. in Huang 116).

Given the harmonious compact the Twins had reached in their everyday life, it is as if jealous spectators secretly yearned for their separation. Huang does not acknowledge—yet provides enough evidence of—a surreptitious desire for their harmonious reciprocity to come undone as a mere façade.

It comes as no surprise that the “mysterious” band focalized most medical experiments, not to mention many episodes of unwonted fondling and groping by self-entitled audience members (305). Such obsessive measurement and representation of the Twins’ connective band confirm that it was, indeed, a “key to their mystery” (48). At one point, a team of surgeons “made an impression with the point of a pin in the exact vertical center of their connecting link (49), wanting to see if both twins felt pain at once, which they did. But discerning the boundary between Chang and Eng was not as simple as drawing a vertical line across their connective tissue. The “mystery” lasted until the Twins’ death in 1874 (Eng survived Cheng only for a few hours, which reinforces unity over duplicity in the framing of their corporeal and psychological identities). Shortly after their funeral, the New York Herald proclaimed: “THE DEAD SIAMESE TWINS. A LIGATURE THAT JOINED THEM IN LIFE AND DEATH” (318). A postmortem examination of the band had discovered a conjoined liver as Chang and Eng’s “tract of portal continuity”: the key to “the key to their mystery” (324).

Today the exhibition of Chang and Eng’s conjoined liver in a can of formaldehyde at the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia perpetuates a troubling logic that takes for granted Chang and Eng’s availability as medical curios. Is not this the same logic that drove Abel Coffin to carry, while on tour with the Twins, “an ample supply of embalming materials” in order to profit from the Twins’ eventual passing and autopsy (72)? What would Chang and Eng, who once punched a doctor for undressing them without permission, think about their ultimate fate? The question, unlike the typical ones that irritate twins and that Huang successfully eschews, is worth entertaining. After all, Huang underscores throughout Inseparable the extent to which the Bunkers valued their privacy, not to mention their struggles to live their adult years far from the stage. Perhaps Huang should have given the Mütter curators a harsher treatment than: “It seems morbidly fitting then that the twins, who were repeatedly exhibited throughout almost half of the nineteenth century, are now perpetually instantiated through the preservation of their liver—exhibited, as if for eternity” (325). Reduced to a shared liver, Chang and Eng are meant to inhabit our memory as a synecdoche, a spine-tingling anomaly eclipsing the Twins’ round personalities, negating them the psychological complexity and depth restored by Huang and Wu. Under the sideshow-esque motto “Disturbingly Informed,” a short blurb in the Museum’s website informs visitors that Chang and Eng “came” to the United States “to tour and speak,” presenting them as orators rather than exploited medical curiosities. ³ Huang’s inattention to such an obvious distortion hampers his case.

Such a benign stance surprises one all the more in light of Huang’s early injunction of a contemporary “historical moment when we see, once again, a rising tide of human disqualification, of looking at others as less than human or normal” (xi). Giving Huang “an acute sense of urgency” (xi), today this “tide” ripples in President Trump’s anti-immigration rhetoric, in his (applauded) mockery of a reporter with chronic arthrogryposis, in every bar where Friday-night dwarf-tossing is still a thing, and in a generalized perception of disabled pensioners as nanny-state parasites. True, there is a stretch between these aggressions and the display of a human organ in a science museum; however, any reconsideration of the freak show and its origins should confront us with our assumptions about the ownership, spectacularization, and consumption of bodies that are not our own. If there is a need to revisit Chang and Eng in the era of Trumpism, trutherism, and the alt-right, then one needs more than winks to suture the connections. Point fingers and name names. Uncanny iterations of Americans’ worst proclivities in the past call for a harsher tone. The monster remains us.

A more focused discussion of the Mütter exhibit could have also taken the space of several digressions. Given Huang’s multi-directional research, one understands—in most cases easily forgives—this rambling disposition, yet a sharper editor would have downsized, for example, the long section on Nat Turner’s rebellion. Its connection to Chang and Eng proves rather speculative, dabbling with how Chang and Eng may have reacted to the news of a brutal slave uprising, knowing themselves to have occupied a similar position in their early career (118-22). The brief mention of the Twins’ failed gig in Virginia shortly after Turner’s execution does not justify such a lengthy excursus. Neither does this loose sequitur: “After their alarming experience in Virginia, Chang and Eng were inspired to plan their own revolt, though one less violent than the Turner insurrection” (133). In fact, Chang and Eng’s later embrace of slaveholding and Southern principles undermines Huang’s suggestion that the Twins gained awareness of their non-freedom via Turner’s or any other slave revolt or abolitionist circle. While the Twins eventually broke free from indentured servitude, they were willing to perpetuate a social system premised on the ownership of black bodies as tools for labor, economic advancement, and sexual gratification. Inseparable makes clear that Chang and Eng perfectly understood these three dimensions in their stint as Southern planters. One even detects a tinge of schadenfreude when Huang narrates how Chang and Eng, grown astute traders in human chattel, had to re-commodify themselves and return to the freak-show circuit after Emancipation (162).

If there is a need to revisit Chang and Eng in the era of Trumpism, trutherism, and the alt-right, then one needs more than winks to suture the connections. Point fingers and name names. Uncanny iterations of Americans’ worst proclivities in the past call for a harsher tone. The monster remains us.

Despite a few tangents, omissions (e.g., Chang’s alcoholism—does not this indicate a growing schism in the Twins’ final years?), and facile similes (“The advancing medical science and the time-honored freak show became, like the bodies of Chang and Eng, intertwined,” 69), Inseparable intervenes forcefully in American Studies, Asian American Studies, the Health Humanities, and Disability Studies. Huang is the first scholar to examine closely the Twins’ origins in 1810s Siam. “Part One” of Inseparable conveys the everyday reality of a land too often viewed through the lenses of orientalist fantasy. Indeed, the ingredients are there: whimsical monarchs, exotic commodities, and European men of fortune such as Robert Hutner, the Twins’ discoverer. But Huang cooks a different recipe. In his valuable account, Siam emerges as a haven of ethnic tolerance and financial stability for Chinese migrants. Chang and Eng were born from one of the period’s many humble, yet prosperous, Chinese-Siamese marriages. Childhood aboard the family’s sampan instilled in them a talent for showmanship. Huang increases thus our sense of the Twins’ agency by tracing their business acumen to their early days selling ducks and century eggs along the Meklong river, already showcasing their anatomy as bait for customers. Huang makes here two important contributions to Chang and Eng’s scholarship. First, he confirms that the Twins were ambitious entrepreneurs before being trained by US managers and showmen. Secondly, the Twins enjoyed a certain prosperity in their home country, which would explain their lifelong penchant for refinement and luxury. This explains their stage aesthetics and, more importantly, their transformation into Southern planters. If slaveholding was the closest one could get to an aristocratic lifestyle in the nineteenth-century United States, then this step seems logical in the Twins’ trajectory.

The magisterial framing of the book deserves additional commentary. One must struggle to imagine a scene so peripheral and, at the same time, so profoundly American as a game of chess played in Atlantic waters between a freed African slave turned president of Liberia and a pair of conjoined Siamese twins naturalized into U.S.—and eventually Confederate—citizenship. This encounter, revealing so much about the United States without it anywhere in sight, kicks off Inseparable. But if Huang’s overture unfolds many miles away from the nation, his epilogue brings us to the Twins’ original plantation near Mayberry, NC, a community whose other pop-culture claim to fame is hosting the über-Americana Andy Griffith Show. There, “to open the door to the twins’ show in the basement of the Andy Griffith Museum is in some sense to reveal the ‘underbelly’ of America, to see how the normal is built on top of the abnormal” (332). Prologue and epilogue bookend thus a rigorous, riveting, and ethically-minded demonstration of how normal—and normative—popular culture in the United States has pivoted on spectacles of corporeal otherness/our-ness such as Chang and Eng’s conjoined body. “Step right in, ladies and gentlemen, and see you for yourselves”—cries the carnival barker. Inseparable confronts us with the ease with which we have heeded this call.