The Rise and Fall of St. Louis and The Broken Heart of America

With stunning power, a new history of our town tells an ugly story of race, money, and oppression.

October 29, 2020

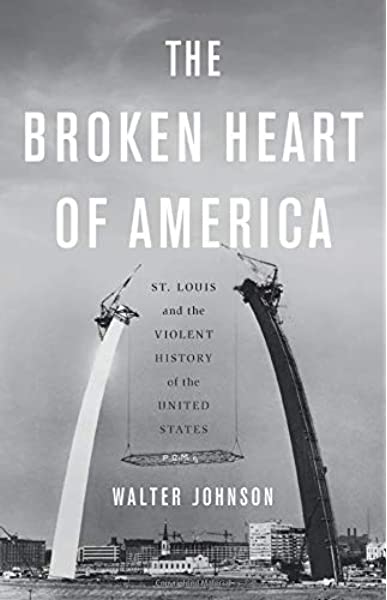

The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States

On the day I started my job at Washington University, an HR rep asked a group of us to introduce ourselves. I said I grew up in southern Illinois, where St. Louis was seen as the big city. I left the region to join the army, went to college elsewhere, worked a corporate job in Chicago, and taught at three universities around the country, but my recent arrival in St. Louis meant I had finally made it. I got the laughter I deserved.

It is true many of us saw St. Louis as the symbolic center of the country, for better reasons than mere regionalism. It had important industries, especially aerospace and defense, and a Federal Reserve Bank. Major highways, rail lines, and national rivers converged to tie east to west and north to south. Those rivers had made St. Louis rich, originally, and the city was famous as the “Gateway to the West.” It was also a primary destination in the Great Migration. Long before I heard the expression “a northern city with southern exposure,” it was how I thought of St. Louis.

Even as a child I knew how its landscape seemed representative of the whole. My mom drove me north of the city to see the Missouri River coming in from the Western Plains I had not seen yet, and the Illinois River coming from Chicago, some faraway, colder place. The main artery of the continent, the Mississippi, flowed eternally past St. Louis, joined the Ohio River not far from my hometown, then rolled down to Memphis and New Orleans. South of St. Louis were the heavily-wooded, limestone-and-dolomite Ozark Plateaus, an ancient geography.

In my kid imagination, St. Louis contained all times at once too. Its summer heat was positively Cretaceous. Cahokia, one of North America’s great civilizations, was nearby, wondering what to do with DeSoto if he ever showed up. Native Americans, voyageurs, and Big Knives still stalked the Revolutionary wilderness around old Fort de Chartres. Ironclads built in St. Louis were beating down to Vicksburg, and Twain was just upstream, out of sight around the bend.

My childhood experience of St. Louis was that of any daytripper’s … Just crossing the River meant breathing in the taste of sweet anise from the licorice factory hard against the bridge.

None of these fantasies seemed outlandish, since the reality was nearly as odd. The Gateway Arch, begun the year I was born, was complete by the time I registered it: a glittering, sinuous curve standing on its own two legs,’60s-hip but nodding to the stainless-steel SS Admiral at its feet—in those days, an honest-to-god sidewheeler with steam boilers under its art-deco skin. Shining jetliners, only a decade in use, hung in the sky above the Eads Bridge, which had opened in 1874 and was still how we crossed the River. A modern city had sprung to life from the clay of that brown god.

My childhood experience of St. Louis was that of any daytripper’s: The downtown department stores, in the time before malls, filled with wonders at Christmas; a nearby cafeteria that was one of my mother’s favorite restaurants in the world. She drove two hours each way to take me to weekend classes at the St. Louis Zoo, where Marlin Perkins was Director, and to the Planetarium, Art Museum, and theater in the park at The Muny. Just crossing the River meant breathing in the taste of sweet anise from the licorice factory hard against the bridge.

As for the people who actually lived in St. Louis, I did not know any, but I was interested. For a white kid in from coal country, which had more than its share of probable sundown towns, seeing so many Black people all at once was a revelation and a relief of sorts: at least we did not have to act as if sitting together was unusual.

I do not remember if I knew the word “integrated,” but I understood the idea, and I thought St. Louis was and always had been equitable in that way, at least since the Civil War. I pictured the relief of fleeing slaves when they had arrived. It made me proud that St. Louis was the city I lived closest to, as I was proud that Lincoln’s home and tomb were in my state.

The city seemed vibrant then, and I assumed its resources belonged to everyone. I did not understand why East St. Louis, which we drove through to get there, looked so stricken. As the years went by, more of the city itself failed, and my mother did not visit as often.

St. Louis was also a regional hub for military enlistment, and I left my childhood there, after a night in a decrepit business hotel contracted by the DoD, and a morning shower in water as brown as the River. I got on a bus for Fort Leonard Wood with my still-childish jumble of impressions of St. Louis, which amounted to this: it is really something. Other than a couple of brief layovers, I would not return for thirty-five years. My opinion has refined but not really changed.

• • •

The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States (Basic Books, 2020) confirms St. Louis as an American nexus, though mostly not in ways I understood as a child. Its author, Walter Johnson, is Winthrop Professor of History and Professor of African and African American Studies at Harvard.

Because it is about our nation as much as it is about one city, and because Johnson frames it as “the two-hundred-year history of removal, racism, and resistance that flowed through the two minutes of confrontation on August 9, 2014”—the killing of Michael Brown, in Ferguson, which touched off Black Lives Matter—the book is for all of us and for now. (12)

St. Louis, Johnson shows, has been both representative and superlative. It was “the epicenter of the nation’s nineteenth-century empire,” where as many as 150 steamboats tied up at the wharf at once, and from which Lewis and Clark left on their errand for Thomas Jefferson. (35) Trappers, miners, soldiers, railroad crews, and generations of white settlers manifestly chased their destinies from the city.

The “first general emancipation” and the “first general strike” in U.S. history took place in St. Louis. German immigrant Joseph Weydemeyer, a friend of Marx and Engels, and “the most prominent communist in the United States at the time of the Civil War,” saved St. Louis for the Union (and maybe saved the Union itself). (133) St. Louis, “one of the most radical cities in the United States,” had a commune for a time, as well as important progressive movements, often led by Black women, which fought for workplace rights we all enjoy, including the eight-hour day. (4)

St. Louis was called “first inland city on the globe” by journalist Horace Greeley, and Walt Whitman, William T. Sherman, and local boosters supported the idea of making it the nation’s new capitol, even if it meant moving the old one “brick-by-brick.”

Industry in St. Louis began in the early nineteenth century with fur-trading and lead smelting, and evolved into milling, meatpacking, breweries, steel mills, and rail works. After the Civil War, the city became a modern (non-furbearing) mercantile powerhouse, with highly-developed trade with Latin America and plans for Asia. Eighty percent of the active-duty Army relied on St. Louis’ Jefferson Barracks for orders, supplies, and reinforcements.

St. Louis was called “first inland city on the globe” by journalist Horace Greeley, and Walt Whitman, William T. Sherman, and local boosters supported the idea of making it the nation’s new capitol, even if it meant moving the old one “brick-by-brick.” (168) By 1890, “The city had the largest train station, brewery, chemical plants, brickworks, and electric plant on the continent.” (201)

The city opened the first public high school for Black students west of the Mississippi, which still exists, and Black artistic genius developed “one of the definitive art forms of the twentieth century—ragtime,” as well as distinctive jazz and rock ‘n roll. (196)

During the course of the 1904 World’s Fair, “when all the world was assembled in tribute to the city’s greatness,” twenty million people attended, including Woodrow Wilson, Henry James, Mark Twain, a young TS Eliot, Thomas Wolfe, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Kate Chopin, who died after a day in the Cretaceous heat. (181)

Hot dogs, hamburgers, cotton candy, peanut butter, and ice-cream cones “are credibly said to have been invented (or at least introduced as mass-market staples) on the grounds.” New technologies made their first appearances, including the world’s first air-conditioner, cordless phone, electric wall plug, fax, and answering machine.

The Olympics were held at Wash. U. during the Fair, as well as an academic conference that intended to present “a unified view of the whole of reality.” (203)

But Johnson uses many of these proud events in the city as examples of the problem he works on throughout the book. His approach is “‘racial capitalism’: the intertwined history of white supremacist ideology and the practices of empire, extraction, and exploitation. Dynamic, unstable, ever-changing, and world-making,” St. Louis is both gear and engine. (6) He quotes Walter Benjamin: “There is no document of civilization that is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

The 1904 World’s Fair proudly displayed “the largest human zoo in world history,” ten thousand people from around the world meant to show the supposed progression from savagery to higher (white) humanity—“a story about racial progress.” They included African slaves and the defeated Apache leader Geronimo, forced to pose for photos with white tourists and to pretend to be Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull in reenactments of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. One of the slaves, a young man named Ota Benga, “under the auspices of the white supremacist racial theorist Madison Grant … was kept in a cage at the Bronx Zoo” after the Fair. Then he worked in a tobacco factory, and at the age of about thirty-two, “built a large fire, danced, and then shot himself through the heart.” (206)

The Fair, Johnson shows credibly, “offered a powerful argument about the solvent character of imperial whiteness. It offered a dirty bargain to the working whites in a city with an enduring strain of labor radicalism…. Come spend a day enjoying yourselves…lay down your placards and your pistols, and take up your rightful place in the front rank of the civilization and the ‘march of progress.’” (210)

The Fair, Johnson says, was a way to “pacify the city’s white workers and ensure their proper alignment with the course of freedom-through-capitalism and imperial progress,” which would ultimately support President Theodore Roosevelt’s announcement (while touring the Fair) that the United States intended to become the Western hemisphere’s “policeman.” (214-15)

His approach is “‘racial capitalism’: the intertwined history of white supremacist ideology and the practices of empire, extraction, and exploitation. Dynamic, unstable, ever-changing, and world-making,” St. Louis is both gear and engine.

Chapter by chapter, Johnson reveals iterations of the same problem, the “crucible of American history,” in which having a United States of America as we know it meant the removal of Native Americans and African Americans. (5)

After the Civil War, for example, 80 percent of all US Army troops were west of the Mississippi, headquartered and supported by Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis. Many massacred Native Americans in “Indian wars” to clear the way for white migration and settlement. The (military-enabled) “railroadization and racialization of the West went hand in hand,” Johnson says, and St. Louis was the “morning star of US imperialism” and “the largest forced relocation camp on the continent.” (5, 165, 34)

St. Louis is also important for the landmark civil rights cases tried there, involving slavery, housing, education, and employment. It is “only a seeming contradiction,” Johnson says, that Dred Scott, “the defining ruling in proslavery jurisprudence…should have come from St. Louis, a city where slavery played a marginal role in the economy…. [T]he deeper truth is that slavery in St. Louis was uniquely precarious, and because it was uniquely precarious, it was uniquely violent.” (91)

His many examples include the lynching in 1836 of Francis McIntosh, a free Black sailor attacked on the St. Louis waterfront by two unknown white men, whom he killed in self-defense. They turned out to be a deputy and a constable who had the wrong man. Abraham Lincoln said of McIntosh, “His story is very short, and is perhaps the most highly tragic of anything of the length that has ever been witnessed in real life.”

McIntosh was grabbed by a mob, as Lincoln explained, “dragged to the suburbs of the city, chained to a tree, and actually burned to death; and all within the single hour from the time he had been a free man, attending to his own business, and at peace with the world.” (74) As the flames rose (aided by the fire department) he begged the mob to shoot him, but they would not. His corpse and the charred tree were left as a warning to others about what Lincoln called the (white) “mobocratic spirit.” (76)

The Broken Heart of America could be important to those who deny systemic racism—if they would read it. It reveals much about the continuing legacies of slavery and Native American genocide in our society, still evident in the daily news.

The violence spread, even within the white community. Elijah Lovejoy, the famous Presbyterian minister, journalist, and editor, reported McIntosh’s murder in a St. Louis paper, so a mob forced his relocation to Alton, Illinois. Then they famously burned his warehouse, shot him mortally, broke up his press, and threw it in the River. Lincoln was prompted by the case to warn, “Whenever the vicious portion of the population shall be permitted to gather… this government cannot last.” (77)

The Broken Heart of America could be important to those who deny systemic racism—if they would read it. It reveals much about the continuing legacies of slavery and Native American genocide in our society, still evident in the daily news.

Johnson refers to James Thomas, for instance, a free Black in St. Louis in the years before Dred Scott, who wrote about poor whites “pushed to the margin of the economy,” who “‘attempted to bring themselves into notice of the better class’ by policing the Blacks, arrogating themselves the ‘duty to watch the Negroes as a measure of public safety,’” and roughing people up in a “misbegotten effort to gain the favor of their social betters.” (90)

Johnson offers several micro-successes in the St. Louis community at the end, but the book feels deeply pessimistic. Because its reason for being, in a sense, is the killing of Michael Brown, it is impossible not to remember that the book dropped only a month before George Floyd died under the knee of Derek Chauvin.

Similarly, Johnson covers historical “urban ‘redevelopment’ by bulldozer”; the “sequestration of poor Black people in [nationally-notorious] housing projects”; postwar white flight; and the birth of the “Nixonian New Right and the militarization of policing.” All his examples are from the past, of course, and in St. Louis, but all are similar to things happening across the country today, from racial profiling to militias to autonomous zones.

The book shows times when our nation had the chance, tragically, to make other choices that might have led to more unity and greater prosperity for all. (These examples should not be mistaken for single-minded critiques of the Right. Johnson offers examples, for instance, of the “problem that has bedeviled the American left down to the present day: a failure to reconstruct a vision of democracy rooted in European social theory around the specific history of the United States.”) (120)

Johnson offers several micro-successes in the St. Louis community at the end, but the book feels deeply pessimistic. Because its reason for being, in a sense, is the killing of Michael Brown, it is impossible not to remember that the book dropped only a month before George Floyd died under the knee of Derek Chauvin. Millions have taken to the streets around the world in protest, during a pandemic, yet in the United States there is a feeling of acceleration of injustice, not its slowing.

As Johnson says, “The cover of whiteness, it turns out, offers incomplete protection from the violence unleashed in its own name.” (9)

Some worry what we will do without the old narratives, if they get pulled off their plinths with chains. These were always only simple approximations in service to power. What we need is real stories, stories with complexity, stories for adults.