Effa Manley’s life is the stuff of which role models are made. From 1935 to 1948, she was co-owner of the Brooklyn-turned-Newark Eagles of the Negro National League, working tirelessly for the game without the benefit of an official title with the team or the league. She is the first—AND STILL ONLY—woman inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, class of 2006.

As such, her story must be told to audiences of all ages. Girls—and boys—need to be able to envision themselves as a sports executive just as easily as they see themselves earning glory as a player or coach. Effa Manley’s ability to develop business acumen and her deft maneuverings of racism and sexism offer a worthy blueprint.

The challenge when delivering her story to 10- to 14-year-olds arises in the controversies, discrepancies, and distractions that inevitably come with being a trailblazer: Questions about her race and parentage. The nuances, ethics, and utility of “passing” as White yet assuming a Black leadership role. The influence of arriving in Harlem during the Renaissance. The ethics of investing income from illegal activities into a legitimate business. The art of negotiating contracts—not all of them in writing—while not holding an official title with the contracting organization. The boldness in standing up to the Commissioner of Major League Baseball. The act of balancing the future of her players with the decline of the source of her own income, notoriety, and influence.

Girls—and boys—need to be able to envision themselves as a sports executive just as easily as they see themselves earning glory as a player or coach. Effa Manley’s ability to develop business acumen and her deft maneuverings of racism and sexism offer a worthy blueprint.

Born in Philadelphia in 1897 (give or take), Effa Manley never shied from—in fact, seemed to embrace—controversy, the limelight, the burning issues of the day, and the gray areas between Black and White, seasoning them with spice, sizzle, and drama. Her biographers have free range to explore these issues, most notably James Overmyer’s Queen of the Negro Leagues: Effa Manley and the Newark Eagles (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1993) and Bob Luke’s The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2011).

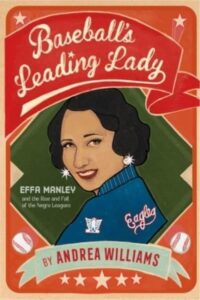

Yet Andrea Williams’s Baseball’s Leading Lady must inform and respect her audience of 10-14 year-olds. So, how do you simmer the story to its essence? How do you frame the controversies? What do you remove? Williams answered those questions by sidestepping a biography. Rather than the personal details and words of Effa Manley, Williams relies on the historical context of systemic racism, the Harlem Renaissance, the Negro Leagues, and the integration of baseball to illuminate Manley’s influence, significance, and legacy.

Roughly one-third of the book deals with the Negro Leagues before Effa and her husband, Abe, became owners in 1935. Having worked at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum fresh out of college, Williams put the museum’s archives to good use and provides her young audience with a lean, efficient, athletic survey of the Negro Leagues’ formative years. She includes background on the origins of the gentlemen’s agreement that kept Blacks out of the major leagues and sketches the characters who shaped the Negro Leagues through the early years. She gives abundant credit to founders, such as Rube Foster, Cumberland Posey, and Gus Greenlee, who laid the groundwork upon which Effa and Abe Manley trod.

Born in Philadelphia in 1897 (give or take), Effa Manley never shied from—in fact, seemed to embrace—controversy, the limelight, the burning issues of the day, and the gray areas between Black and White, seasoning them with spice, sizzle, and drama.

Williams also notes that Effa arrived in Harlem fresh out of high school in 1916, the same year as activist Marcus Garvey, to start a career in hat-making, at the time a field open exclusively to Whites. Either through passion or simple osmosis—Williams does not pick a side—Manley got politically involved. A year before taking over as owner, she helped organize and then walked the picket line as part of the effective “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign against Blumstein’s Department store in Harlem, which refused to hire Black employees.

Some passages present Effa as a visionary, though her status as co-owner, woman, and her lack of a defined role seems to blunt her influence with the powers-that-be, both in the Major and Negro Leagues. Some examples:

- She advocated for a league president with no team affiliation and no ties to the booking agents who took hefty fees for reserving the Major League stadiums that most Negro League teams used. This campaign was to no avail, which led to the siphoning of money away from players and owners to the middlemen.

- She was among the league’s strongest advocates for Black newspapers publishing statistics from each game, either sending box scores to the local papers herself or having the team manager do so. Even though her fellow owners were not always as diligent as she, these records now represent a treasure trove for historians.

- She was perhaps the most vocal of a minority of owners who saw correctly that the signing of Jackie Robinson was a mortal blow to the Negro Leagues. She believed that White teams should pay for signing the stars that Negro League owners had invested so much time and effort in developing. Thus, she led the charge in challenging Major League owners when managers began signing players. MLB owners felt empowered by the often casual relationship between some Negro League owners and players. For some players, contracts did not exist on paper. For others, their contract failed to include a reserve clause, which controlled the rights of a player for the entirety of his career, unless the team waived, sold or traded him and entitled the team to legal remedy if violated.

- She also floated the idea, again to no avail, that the Negro Leagues form a partnership with Major League Baseball that would have led to Black-owned teams becoming part of the farm system.

Williams does a stellar job of laying out the strategy and execution of Manley’s negotiations with Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck in purchasing the contract for Larry Doby, the star of her Newark Eagles who became the first Black athlete to play in the American League. Manley’s blueprint for negotiating set a precedent that helped her fellow owners recoup some of the money that they otherwise would have lost through contract raiding.

This is the Effa Manley that Williams wants to connect with her young audience. So for the most part, Williams eliminated the bulk of the ambiguity. But in doing so she also eliminated a heaping helping of personality.

For example, she could have more thoroughly explored Effa’s use of her mixed ethnicity. Williams cites U.S. Census records indicating that Effa’s mother, Bertha Brooks, was of both German and Black descent. Bertha’s first husband, Benjamin Brooks, was a Black man, though she cites evidence that Effa was the product of Bertha’s affair with a White man, John Bishop. Effa grew up in a Black neighborhood with the siblings fathered by Benjamin Brooks. Williams provides details of Effa’s deft maneuvers through both worlds, illustrating how Effa used the ambiguity to her advantage and blew with the wind, using her light skin as often as she proclaimed her Black roots to advance her players and the game more than herself.

Her relationship with Abe Manley is another. Williams dismisses this rather quickly, mentioning that they met at a World Series game between the Yankees and Cubs in 1932. A few sentences later, they are married. Oh, yeah, and she slips in there that Effa had been married briefly before. Granted, the narrative is not a teen romance or a Lifetime movie script, but the intended audience might have enjoyed a few more juicy details, other than a snapshot of Abe, 24 years Effa’s senior, taking her to Tiffany’s to pick out a five-carat diamond engagement ring.

This is the Effa Manley that Williams wants to connect with her young audience. So for the most part, Williams eliminated the bulk of the ambiguity. But in doing so she also eliminated a heaping helping of personality.

Likewise, Abe’s financial dealings are summarized. His money, Williams writes, came from successful investments in real estate and racketeering, portrayed as a way to pump illicit money from non-sanctioned lotteries back to better the community as a whole. The couple initially purchased the Brooklyn Eagles, who played in Ebbetts Field, but moved the franchise after acquiring a semi-pro team based in Newark, as settlement of the owner’s $500 debt to Abe. Shortly after moving the team, Effa took over day-to-day business operations: arranging schedules and travel, managing payroll, buying negotiating contracts, and handling marking and promotions. Williams also makes numerous references to the team losing money but is short on details as to how the Manleys kept the team afloat for thirteen years.

And, just what did she do with the final three decades of her life? A whopping 289 of the 294 pages of narrative are devoted to her life before and during ownership. The last three-plus decades of her life earn little mention.

One other weakness of the book is what seems to be a gratuitous intrusion of excruciating game details in the early pages, where Williams recounts the only Negro League World Series victory for the Newark Eagles in 1946, just before Robinson broke the color barrier. There is a second “game story” near the book’s conclusion. While they illustrate Williams’s familiarity with the nuts and bolts of baseball on the diamond, they do nothing to heighten drama or advance the narrative.

Williams provides details of Effa’s deft maneuvers through both worlds, illustrating how Effa used the ambiguity to her advantage and blew with the wind, using her light skin as often as she proclaimed her Black roots to advance her players and the game more than herself.

Game stories do not a sports writer make.

With little of Effa’s own words and personal details, the book is less a biography than an overview of how systemic racism played out in her childhood, in her young adulthood living in Harlem during the Renaissance and in the arc of the Negro Leagues. Thus, the book becomes more a survey of history: how racial forces shaped Effa Manley and how she reshaped those forces to benefit herself, her players, and the league. Despite the lack of Effa’s voice, this is a story worth telling and even more worth reading for a young audience.