Our current moment is a mind-numbingly literal one: base, crude, and mean. Plenty of writers have bemoaned the “lack of nuance” in today’s socio-political discourse, so I will not belabor the point except to say that it is manifest in more than the boorish cruelty of the president’s Twitter account. Our very notion of the possible is diminished by the stultifying lack of imagination (preening itself on its own “realism”) regarding any viable path to social change. In a world where all the rules are one-dimensional, some people are going to be disposable.

How much of this can be chalked up to poetry? Or, more specifically, to a lack thereof in daily political life? Gone are the days when thousands would pack into auditoriums to hear Adrian Mitchell excoriate the Vietnam War, or flock to public squares to watch Yevtushenko upbraid the Soviet bureaucracy. Looking at the Anglo-American world as it exists today, it seems fair to say we live in the least poetic culture yet in history, a time when more people are alienated from the subtle immediacy of the written or spoken word than ever before in the modern era.

Not that people no longer care for poetry. Any number of campus poetry slams, small journals, neighborhood bookshop readings, or under-the-radar rap battles would very much suggest otherwise. But these fragmented experiences no longer contend for influence in the world at large. Forty years of cuts in education and the consolidation of the culture industry into fewer and fewer hands have diminished the role of literature in public discourse.

The literary establishment has not always praised him. Johnson’s unsparing, often violent depictions of Black British life, his open embrace of Marxism, and his affinities with reggae and decision to write in phonetic patois, have made him the subject of denunciation and scapegoating. In 1982, in the wake of the Brixton uprising, The Spectator newspaper accused him of helping to “create a generation of rioters and illiterates.”

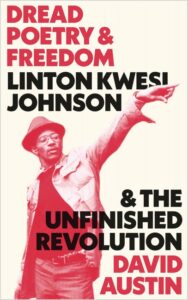

Enter David Austin, and his record collection. Austin is the author of Dread Poetry and Freedom: Linton Kwesi Johnson and the Unfinished Revolution. Though relatively little known in the United States, Johnson–Jamaica-born but living in Britain for the past sixty years–is a towering presence in the poetry of Black Britain and the Black diaspora. One of only three living figures whose work has been published by Penguin Modern Classics, he is currently the only Black poet to be featured in the collection. His records, starting with 1978’s Dread Beat an’ Blood, featuring his poems recited over bouncing reggae instrumentation, are some of the best-selling albums in the genre, and established him as an innovator in “dub poetry.” Contemporary critics have called him a voice for the children of Windrush, the British race and deportation scandal, even carrying on the tradition of Jonathan Swift and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The literary establishment has not always praised him. Johnson’s unsparing, often violent depictions of Black British life, his open embrace of Marxism, and his affinities with reggae and decision to write in phonetic patois, have made him the subject of denunciation and scapegoating. In 1982, in the wake of the Brixton uprising, The Spectator newspaper accused him of helping to “create a generation of rioters and illiterates.”

In other words, Johnson is something that does not quite compute in the contemporary imagination: a poet of political consequence. This is what Austin dedicates Dread Poetry and Freedom to fleshing out fully. He writes:

While it would be more than presumptuous for me to suggest that my interpretation of Johnson’s poems are even better than his own, and given that this book is grounded in the lofty desire to make a modest contribution towards creating a just and equitable world, Dread Poetry and Freedom is not about Linton Kwesi Johnson’s poetry; or put another way, it is about his poetry in so far as his poetry qua poetry is an expression of politics, or provides poetic insight into politics, again, premised on the presumption that poets are well placed to inform our understanding of political possibilities. (6)

It is an ambitious, albeit treacherous, creative-intellectual exercise. To look at political economy in terms of literature (and vice versa) can reveal surprising insights. It can also produce pitfalls, resulting in either a wooly-minded conception of politics or a dry, utilitarian outlook on art. A great many writers and theorists fall one way or the other, further complicating the possibility of giving form and shape to a political imagination.

Austin’s book follows a heavily biographical course. This does not just mean looking at Johnson’s itinerary–born in Jamaica, migrating to Britain as a youth, joining the British Black Panther Movement and the Race Today collective–but also painstakingly examining his influences, filling out the picture of Johnson’s life and revealing dimensions of his artistic choices. The choice to write in patois is explained by recounting a television appearance in which the poet traded playful barbs with Pan-African Marxist writer CLR James over the worthiness of Shakespeare; Johnson is a great admirer of James’s work, less so of Shakespeare.

Specific poems, like his mournful “Reggae Fi Radni,” are examined through the relationship Johnson had with their subjects. In this case, it is his friendship with Walter Rodney, Guyanese historian and social activist whose assassination in 1980 provoked Johnson to write an elegy for him. Austin dissects the poem, often diverting the narrative to explain Rodney’s thought, comparing and contrasting it with that of Johnson, again vis-à-vis CLR James.

Other sections of the book look at a series of Johnson’s poems through a specific lens, for example feminist analyses of Johnson’s poems in relation to Black diasporist and feminist writers like Jean “Binta” Breeze, May Ayim, and d’bi young anitafrika. Still others examine Johnson’s insights into prospects for socialism through his many poems on the drastic change to life that came with the fall of the Soviet bloc. Johnson’s own socialism–influenced as it is by stridently dissident and libertarian-minded leftists like James and Rodney–has never had much truck with bureaucratic, Soviet-style communism. But Austin sees in many of the poems from that era–poems like “Mi Revalueshanary Fren” and “Di Good Life”–bold willingness to reflect on a new reality. He also hears in them a vision of time and life, work, and leisure that arguably is truer to what Karl Marx had in mind than anything emerging on the other side of the iron curtain.

• • •

All of this makes for interesting analysis. But is it effective? Is it successful in constructing a vital alternative political-poesy that stands on its own, particularly given how multi-faceted and potentially unwieldy the theory and analysis can be?

The best case for the affirmative comes when Austin examines Johnson’s work in relation to two men: Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire. Fanon’s books–The Wretched of the Earth, Black Skin, White Masks and others–have seen a resurgence in popularity over the past few years, particularly spurred on by the rise of Black Lives Matter. Césaire less so, but given that Fanon was his student, it is not difficult to trace his influence in the current moment either.

Taking a cue from Johnson’s own penchant for wordplay, Austin coins the terms “Fanon-menology” and “Césairealism” to illustrate the specificity of each thinker’s influence on Johnson’s work. It is a refreshingly playful device and helps in fleshing out the exact nexus of art and politics Austin is trying to identify, at least in terms of the Black radical imagination.

In Fanon’s work on anti-colonial phenomenology, Austin identifies an explanation for why Johnson’s reggae affinities and insistence on his patois cause more conservative commentators to clutch their pearls. In Austin’s view, this can be likened to the process by which the colonized reclaim their identity, outside the parameters of the colonizer. Johnson himself has written on this. His 1976 essay “Jamaican Rebel Music” for Race & Class (also cited by Austin) is essentially a Fanonian analysis of reggae:

The music invokes what Fanon calls ‘the emotional sensitivity’ of the oppressed and gives vent to it through dance… But it so happens that, at times, the catharsis does not come through dance, for the violence that the music carries is turned inwards and personalized, so that for no apparent reason, the dance halls and yards often explode into fratricidal violence and general pandemonium. (86)

In other words, the particularity that emerges from the blending of these sounds and linguistics can be interpreted as a meditation on the tensions of oppression, violence, and subjectivity on the terms of the oppressed. Austin builds this out, finding touchstones in Johnson’s poems from this era. “Dread Beat an’ Blood” and “Five Nights of Bleeding” describe the “fratricidal violence” in Black and Caribbean neighborhoods, but in a way that shuns the moralism of the White gaze.

They are also counter-posed by Austin to poems like “Fite dem Back,” which celebrate violence waged by Blacks and Asians against White supremacists such as the National Front, who were then gaining in influence in Britain (“Fashist an di attack | We wi’ fite dem back | Fashist an di attack | Den we countah-attack”). Austin contrasts these two kinds of violence as progress, moving toward what South African theorist Ashley Dawson describes as “Fanon’s discussion of the humanizing effect of counter-violence within a context of racial violence and terror.”

In the author’s view, these are poems that provide unique insight into a certain facet of the Black diasporist experience. Fair enough, but it leaves open the question about whether the poems “work as art,” for if they do not, they cannot work as politics.

It is here that Austin’s reminder of Césaire–the Martiniquais communist, surrealist poet, and confederate of André Breton—is so deft, placing Linton Kwesi Johnson squarely in the tradition of surrealism. This may upset those art historians who cling to a conventional understanding of surrealism. But then, “a conventional understanding of surrealism” is something the surrealists themselves would spit at. Most of the original generation, as Austin recounts, were some form of communist or anarchist, and exhibited a disdain for colonialism along with Eurocentrism and bourgeois society more generally. Perhaps most importantly, they saw themselves less as an “art movement” and more as the architects of an all-encompassing practice of liberation that wove the artistic into an increasingly impoverished existence.

In the author’s view, these are poems that provide unique insight into a certain facet of the Black diasporist experience. Fair enough, but it leaves open the question about whether the poems “work as art,” for if they do not, they cannot work as politics.

As an exemplar of what one of the movement’s own publications called “surrealism in the service of the revolution,” Césaire’s legacy is crucial here. His description of surrealism as “a process of disalienation” fits with Fanon’s reclamation of subjectivity. His role as key architect of the Negritude movement in turn makes him particularly useful in understanding Johnson’s relationship to reggae and Rastafari culture. Despite the poet’s atheism, he recognizes the importance of the latter in constructing a Black identity apart from the trappings of Europeanism. As Austin writes,

Negritude and Rastafari stressed the repossession of African identity in response to its suppression during colonization, and both movements possess(ed) the metaphysical and/or surreal that is rooted in the creative manipulation of language. While in Rasta’s case, this involved the creative use of Jamaican vernacular, including linguistic inversions such as ‘downpressed’ (as opposed to oppressed), Césaire’s poetics were largely rooted in the creative manipulation of French … [M]y point here is that as a dread poet in the 1970s Johnson was inspired by the dread lyricism of Jamaica, and captured the experience of dread in England by combining the elements of reggae, Rastafari and Césaire’s surrealism in his apocalyptic synoptic of dread in England and Jamaica. (47)

Readers will want to listen closely to Johnson’s work to gauge the accuracy of this interpretation. The hypnotic thump of reggae and dub have a specific interplay with the words and their delivery. If one accepts their logic then they hear, in fact, a rather weird and yet familiar world being reflected back to them: violent, unequal, often coming apart at the seams. As if something “other” were being revealed despite all attempts to conceal it. As if the truth being told is only fully uncovered by how it is told.

As artistic profile then, Dread Poetry and Freedom is successful. In fact, it also succeeds in constructing a worthwhile rubric through which political art can be viewed. Though this may be accidental, it also unveils a broader problem, albeit one well beyond the scope of the book. That is, if poetry can play a role in “informing our understanding of political possibilities,” can it play a role in widening those possibilities?

It is a slippery question. Of course a poem by itself cannot physically move anything. Nor can a poet with mere words. Still, the notoriety and influence achieved by someone like Johnson, at least in Britain, points to an affinity between a certain kind of art and a certain kind of politics, as well as the role each can play in making room for the other.

Johnson’s very first poems were published in Race Today, a radical anti-racist magazine closely allied with British Black Panthers and the British left more broadly. It was also close to the Notting Hill Carnival and other cultural institutions that were influential among Britain’s Caribbean community. And thus there was an empirical case to be made that the survival of Black culture was inextricably tied to the fortunes of the far-left. As room was forced open, so could the words of someone like Johnson gain a larger audience, draw attention to society’s fault-lines, and thus the cycle would continue.

Of course a poem by itself cannot physically move anything. Nor can a poet with mere words. Still, the notoriety and influence achieved by someone like Johnson, at least in Britain, points to an affinity between a certain kind of art and a certain kind of politics, as well as the role each can play in making room for the other.

Today this linkage is not so much severed as it is dissolved. Race Today shuttered in 1988. The faces of British power are naturally far more multiracial, even as fear of immigrants persists. We could say something similar on this side of the pond, where the radical and left affiliations that run through the Civil Rights movement and the Black Arts Movement are likewise obscured. People who fifty years ago would have been their enemies can laud their achievements for their own purposes. Subtlety is elided, as are the wrinkles of history, their true meaning obscured along with their outcomes.

In the final chapter of Dread Poetry and Freedom, Austin quotes Robin DG Kelley, himself a formidable scholar of the radical Black imagination: “now is the time to think like poets, to envision and make visible a new society, a peaceful, cooperative, loving world without poverty and oppression, limited only by our imaginations.” (207)

It is a powerful sentiment. But I find myself wanting more than that.

How do we find or create the spaces where a mandate to “think like poets” can become a mass imperative? There is no easy answer. It is a question that preoccupies many a writer, Austin and Johnson included, and I cannot help but think that it is now being posed more urgently than ever.