More than a year after local activists and news articles in Flint, Michigan began reporting on elevated lead levels in the city’s water, Mona Hanna-Attisha was at a cook-out where an old friend, a former EPA researcher, talked about the lead-laden Flint water. Hanna-Attisha, a pediatrician running a small clinic for impoverished Flint children was shocked and somewhat skeptical. Lead, after all, is devastating to the development of brain capacity and neurological functioning of growing children, especially babies. Any level of lead exposure is dangerous. Her friend claimed the preliminary numbers for lead exposure collected by a group of Flint parents and activists were high enough to cause alarm. Where were the warnings? Why were state and Flint officials not alerting the public and providing clean water to the city’s citizens?

Hanna-Attisha, an Iraqi immigrant with a background in environmental research, began to investigate the city’s water supply. What she found was that Flint officials, in an effort to save money, had switched the source of the city’s water supply from Lake Huron to the Flint River, tainting the city’s drinking water with lead. She quickly became a doctor-turned-activist, a public health researcher alternately pilloried by politicians and public officials committed to the cover-up, and celebrated by the city’s activists who needed Hanna-Attisha’s scientific data to protect their children.

For Hanna-Attisha, the American Dream was not an abstract principle. Rather it was an old-fashioned belief in the power of government to do good.

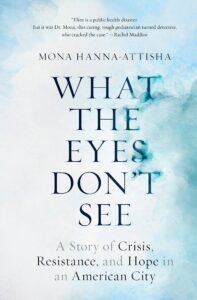

What the Eyes Don’t See is the story of the pediatrician’s fight to protect Flint children from lead poisoning. It details Hanna-Attisha’s use of epidemiological methods to document elevated lead levels in hundreds of Flint children, and tracks the work of coalition-building through scores of meetings, irate phone calls, fighting near-endless official obfuscation, sleepless nights, and ultimately the unyielding support of a small group of researchers and activists. It is a deeply-readable tale of science, public health sleuthing, and a fight for social justice for some of America’s most disfranchised citizens.

Once a prosperous manufacturing town fueled by General Motors auto plants and generous union contracts, Flint was by the late twentieth century one of the poorest cities in the nation. It was the subject of documentary filmmaker Michael Moore’s 1989 film, Roger and Me, a symbol of America’s industrial decline and of corporate America’s throw-away vision of American workers. The GM plants were empty shells, jobs had been sent overseas, and white working-class families had fled to the Detroit suburbs or towns in southern Michigan where lower-paying, typically non-union jobs could be found. Left behind was a city of several thousand largely African American, nearly jobless families living at or below the poverty line. With the city unable to pay its bills, the state appointed a city manager to oversee municipal governance, leaving Flint residents with an impotent mayor and severing the already-powerless population from any democratic process. No one reacted—no one was truly accountable—when local activists appealed for clean water.

Like any good researcher, Hanna-Attisha collected data. She began by documenting the spiking lead levels in the blood of the children tested in her clinic before and after the switch in water sources. When she realized the sample was too small, she hounded municipal and state health department officials, who stone-walled for weeks, refusing to provide her with city-wide numbers of lead testing results. She contacted CDC investigators and worked with other researchers to develop a scientifically sound study to prove the city’s new water supply was the source of the lead poisoning. In the meantime, weeks went by with Hanna-Attisha seething and exhausted by the official dodging and lying. Lead continued to flow from the faucets in kitchens and bathrooms across the city, parents continued to feed babies formula mixed with lead-tainted water, children developed blisters and skin rashes, and a heart-breaking number of babies and small children were hit by irreversible neurological damage.

Hanna-Attisha’s immigrant family and their faith in the American Dream, a rousing counter-piece almost unimaginable in the grim Flint setting, appear throughout this tale of the water wars. The family had fled the horrors of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, landing in Sussex, England and later Detroit. Hanna-Attisha’s father, an engineer, worked for GM, purchased a house in a middle-class Detroit suburb, sent his daughter to medical school and a son to law school. The family, finding safety and prosperity in the United States, held tight to a belief in the freedom and fairness of America.

Like any good researcher, Hanna-Attisha collected data. She began by documenting the spiking lead levels in the blood of the children tested in her clinic before and after the switch in water sources. When she realized the sample was too small, she hounded municipal and state health department officials, who stone-walled for weeks, refusing to provide her with city-wide numbers of lead testing results.

For Hanna-Attisha, the American Dream was not an abstract principle. Rather it was an old-fashioned belief in the power of government to do good. One of her heroes is Alice Hamilton, a Progressive-era doctor who founded the field of occupational medicine to protect factory workers from dangerous chemicals and machinery. Hamilton worked with Jane Addams at Hull House in Chicago and later became a professor at the Harvard Medical School. She is one of a long line of researchers, public health advocates and teachers who shaped Hanna-Attisha’s approach to environmental justice. The book details the history of the field of public health from John Snow’s 1849 documentation of a London cholera epidemic through late nineteen-century urban sanitary reform and the fight for sewers to twentieth-century lead poisoning in household paint. Hanna-Attisha’s months-long campaign to protect Flint children from leaded water is part of her broader faith in public health research, and in America’s ability to address environmental hazards.

And yet, Hanna-Attisha recognizes that racism, poverty, and a history of staggering inequality made Flint’s poor, black population the subjects of the city’s money-saving public health experiment. “Flint falls right into the American narrative of cheapening black life,” she writes. (308) “Flint may be the most egregious modern-day example of environmental injustice.” But it is not the sole example. In the wake of the Flint scandal, several American cities found lead-tainted water, and some have begun the expensive process of replacing lead pipes. Urban infrastructure, long-neglected and under-funded, especially in low-income neighborhoods threatens the health of millions of low-income people of color. The American dream is not available to all.

Hanna-Attisha uses science—and the strength of her personality—to badger, nag, strong-arm and protest, demanding that government do its job. Amidst the months of anger, frustration, and exhaustion, she holds on to the belief that government—local and state officials—can and ultimately will solve the problem.

The book details the history of the field of public health from John Snow’s 1849 documentation of a London cholera epidemic through late nineteen-century urban sanitary reform and the fight for sewers to twentieth-century lead poisoning in household paint.

The surprising conclusion (spoiler alert here) is that the pediatrician proves right. With data in hand, Hanna-Attisha and her collaborators hold a news conference that attracts national media attention and blows open the Flint water scandal. “The Flint water crisis never should have happened,” she writes. “It was entirely preventable… I was just the last piece. The state would not stop lying until somebody came along to prove that real harm was being done to the kids. Then the house of cards fell.” (318)

After that, it was just a couple weeks before the governor apologized, several city officials stepped down from office, and the water source was switched back to Lake Huron. There were indictments of public health staff and state employees for the willful neglect of a public health emergency. And Hanna-Attisha was able to get state and federal officials to commit several million dollars to health and educational programs for Flint families over the next couple decades. Government, when pushed, prodded, and shamed by scientific data, can be a force for good.