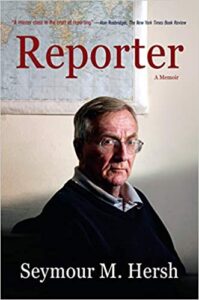

Seymour Hersh is one of the most prodigious investigative journalists in the last 50 years.

The arc of his work as reporter includes uncovering and reporting the My Lai massacre of hundreds of Vietnamese men, women and children by an American infantry platoon in March 1968; developments in the Watergate break-in and cover-up that led to President Richard Nixon’s resignation in August 1974; reports and a book on former National Security Advisor and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, whom Hersh calls, pure and simple, a liar; the torture of Arab prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison after the U.S. invasion of Iraq in March 2003, among his notable features.

Suffice it to say that Hersh has investigated hundreds of stories, mostly involving U.S. government operations in both the military and civilian realms, written 10 books before this fascinating memoir, earned one Pulitzer Prize in 1970 for his My Lai stories, five George Polk Awards in Journalism and many other professional accolades.

As he writes on the first page of his introduction, “I am a survivor from the golden age of journalism, when reporters for daily newspapers did not have to compete with the twenty-four-hour cable news cycle, when newspapers were flush with cash from display advertisements and want ads, and when I was free to travel anywhere, for any reason, with company credit cards.”

Sometimes Hersh seems to have been working only for himself, yet he applied the same detailed reporting and writing in each instance. He may be a reminder that many Americans really do not want to know everything their government does in their name.

Ah, those were the good ole days. How journalism has changed in this internet age, and Hersh is here to tell how it used to be. One cannot help but think today’s world of instant information may not be an improvement for democracy.

Hersh’s world is one of long investigations, finding and reading hundreds of pages of documents–classified and not–and the late I.F. Stone’s approach to journalism: to keep reading government documents and digging even more deeply. This takes a lot of time, and internet-driven “reporting” today often consists of the reporter’s opinion instead of proof of the reporter’s diligence.

“There were no televised panels of ‘experts’ and journalists on cable TV who began every answer to every question with the two deadliest words in the media world–‘I think,’ “ Hersh writes to put his memoir into today’s context. “We are sodden with fake news, hyped-up and incomplete information, and false assertions delivered nonstop by our daily newspapers, our televisions, our online news agencies, our social media, and our President.”

Sometimes his hard work and well-sourced stories resulted in substantial changes in the way the U.S. government worked–at least for a while. Other times, as he laments, no one seemed to be paying much attention for very long.

Sometimes Hersh seems to have been working only for himself, yet he applied the same detailed reporting and writing in each instance. He may be a reminder that many Americans really do not want to know everything their government does in their name.

Hersh notes throughout the saving value of fact-checkers. The best ones are golden. The New Yorker is legendary for its fact-checkers. Without looking for errors, I found two small ones: Hersh calls the First Infantry Division the First Army Division.

And he calls Mordechai Vanunu, the Israeli Jew who revealed Israel’s nuclear weapons program in 1986, an Israeli Arab. Vanunu, who has converted to Christianity and changed his name to John Crossman, was born into an Orthodox Jewish family in Marrakesh, Morocco.

So were there more? I do not know. These examples show the danger of citing fact after fact and leaving out the opinion. Opinions are not necessarily factual, but Hersh’s reputation is built on running down and reporting facts. Yet these errors show that even small ones in a reporter’s text can raise doubts about his or her work that do not go away.

Also suffice it to say that Hersh always has been sympathetic to a leftist critique of the military and civilian government and corporate America, But, as he notes throughout this book, he was sure of the reliability of his sources. He keeps himself out of the story, but he tips his hand by acting on the assumption that there is so much more to the story that we are being told by official sources in the public and private sectors.

As he developed as a reporter, Hersh adopted the practice of always telling his editor or editors who his anonymous sources were. This has become standard practice in high-quality print journalism to avoid the Deep Throat problem that Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward of The Washington Post had when they refused to divulge the name of the late Mark Felt Jr., the No. 2 man at the FBI, when he was giving tips and confirming information they got in the Watergate stories in the early 1970s.

Hersh has worked off and on for two of the best print publications in America, The New York Times and The New Yorker. He had mostly good relationships with The Times’ A.M. Rosenthal and David Remnick of The New Yorker.

He came, and he went, as the stories also came and then played out. Clearly Hersh has been his own man. You could say that his reputation in mostly print journalism allowed him to pick the editors and publications for which he wanted to work.

That also meant Hersh has developed and maintained contacts with a huge file of sources. This book is filled with many insights into how one excellent investigative reporter worked. His rules for serious working journalists and news “consumers” are scattered throughout the book.

Before the Vietnam War began to heat up in the early 1960s, Hersh had served in the Army as an enlisted reservist, which gave him helpful insights into how the Army worked and helped him track down Lt. William Calley, the platoon leader who was convicted in a secret court-martial in Ft. Benning, Ga., of murdering Vietnamese civilians at My Lai.

After his active duty as a reservist was behind him, Hersh moved to Washington and covered the Pentagon for the Associated Press, which gave him many useful insights into how the military bureaucracy works at the highest levels.

It also allowed him to cultivate sources, many in uniform, whom he could meet away from the Pentagon and who would feed him information and documents because they were sometimes deeply troubled about what they saw going on around them.

In the current environment, where leaks and anonymous sources are being vilified by President Trump and his senior aides—a trait for which he is not unique in the history of U.S. presidents—Hersh’s cultivating and use of sources is a reminder that conscience-driven government officials, in and out of uniform, do not comprise a “deep state.” They are men and women who care deeply about the actions of the American government at home and abroad.

Hersh expresses much respect for senior officers and professional government employees who have leaked information and documents to him or cooperated with him. They are the ones who saw things amiss—torture during the Iraq War was but one example–and did not like things being done in the name of the U.S. Army or another service or the United States government.

These are subtleties completely overlooked in the debate sparked by Trump’s self-serving allegations against “the media.”

Speaking of the media, Hersh usually does not have much use for the Washington press corps, which he sees as too much in bed with the powers that be at any one time in the nation’s capital.

Sometimes he would break stories he thought would have a significant impact—and little to nothing happened. No follow-up reporting or stories by other reporters. It was as if, as he tells it, he was operating and reporting from another realm.

Hersh credits several mentors, some towering figures in American journalism, along the way, as he was getting started from an impoverished childhood in a modest Jewish home in Chicago’s South Side. One cannot help but wonder how many young Sy Hershes are coming up to fill his shoes.

The reason, he surmises—correctly, I think—is that those Washington reporters like the cozy relationship they had cultivated with senior administration officials, their daily sources for all kinds of stories, regardless of the administration, Republican or Democrat.

And they like the parties and dinners with sources, often officials in an administration.

“I did not relish being the odd man out in terms of writing stories that conflicted with the accepted accounts, but it was a familiar experience,” Hersh writes in his concluding chapter. “My initial reporting on My Lai, Watergate, Kissinger, Jack Kennedy, and the American murder of Osama bin Laden was challenged, sometimes bitterly. I will happily permit history to be the judge of my recent work.”

Hersh credits several mentors, some towering figures in American journalism, along the way, as he was getting started from an impoverished child in a modest Jewish home in Chicago’s South Side. One cannot help but wonder how many young Sy Hershes are coming up to fill his shoes.

“I was guided as a confused and uncertain eighteen-year-old by a professor who saw potential in me, as did Carroll Arimond at the Associated Press, William Shawn at The New Yorker, and Abe Rosenthal at The New York Times. They published what I wrote without censorship and reaffirmed my faith in trusting those in the military and intelligence worlds whose information and friendship, I valued but whose names I could never utter. I found my way when it came to issues of life and death in war to those special people who had the integrity and intelligence to carefully distinguish between what they knew—from firsthand observation at the center—from what they believed. The trust went two ways: I often obtained documents I could not use for fear of inadvertently exposing the sources, and there were stories I dared not write for the same reason.”

Woven throughout this memoir are Hersh’s dictums about how to be an excellent, groundbreaking reporter. Here is one from that last chapter:

“I never did an interview without learning all I could about the person with whom I was meeting, and I did all I could to let those I was criticizing or putting in professional jeopardy know just what I was planning to publish about them.”

Hersh wrote Cardinal John J. O’Connor, the archbishop of New York, to ask for a meeting to discuss the cardinal’s controversial predecessor, Cardinal Francis Spellman, who by that time had died. The cardinal and the Jewish kid from the South Side hit it off. Their meeting was so pleasant that it ran more than an hour overtime. As they were about to part, O’Connor “threw his arm around me, pulled me close, and said, ‘My son, God has put you on earth for a reason, and that is to do the kind of work you do, no matter how much it upsets others. It is your calling.’”