In my beginning is my end

—T. S. Eliot, “Four Quartets”

Over decades of reading and writing fiction, I have learned two truths about the novel: (1) the second most important line in a novel is the opener, and (2) the most important one is the closer.

The significance of a compelling opening line is obvious, especially if you are the author. That is because a great opener functions as our equivalent of a great pickup line in a singles bar. Our target is that browser in the bookstore (or these days, on Amazon), who has learned that you cannot judge a book by its cover. So she opens your novel to page one and reads that first sentence. If the bait works, she will read the next sentence or two, and if they click as well, she will take you—or rather, your book—home to bed.

And thus, to paraphrase one of the best-known opening lines in literature, “It is a truth universally acknowledged that an author in possession of a good plot must be in want of a captivating first sentence.”1 Examples include:

Call me Ishmael.

—Moby Dick by Herman Melville

It was a bright cold day in April and the clocks were striking thirteen.

—Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell

As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed into a gigantic insect.

—Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

For The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain wrote the greatest opening line in American literature:

You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; but that ain’t no matter.

And, at least for me, One Hundred Years of Solitude, by Gabriel García Márquez crafted the best opening line in all literature:

Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.

Each of those openers lures you into the rest of that paragraph, which pulls you into the novel. Indeed, while “Call me Ishmael” may be the most famous opening line in American literature, the rest of that first paragraph is even more captivating, as is true for the rest of that first paragraph of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.2

The significance of a compelling opening line is obvious, especially if you are the author. That is because a great opener functions as our equivalent of a great pickup line in a singles bar.

So what about the closing lines? Why do I claim that they are even more important than the openers? Ironically, what started me down that path was Joan Didion’s essay on Ernest Hemingway that I happened upon while browsing through an old issue of The New Yorker from 1998. Although entitled “Last Words,” the essay opens with what Didion describes as “the famous first paragraph”—from Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms—which she quotes in full:

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterwards the road bare and white except for the leaves.

As she explains in her own opening paragraph:

That paragraph, which was published in 1929, bears examination: four deceptively simple sentences, one hundred and twenty-six words, the arrangement of which remains as mysterious and thrilling to me now as it did when I first read them, at twelve or thirteen, and imagined that if I studied them closely enough and practiced hard enough I might one day arrange one hundred and twenty-six such words myself.

That got me to reread the novel. For those who have not read it—or have not read it in a long time—the plot is fairly straightforward: Frederic Henry, an American lieutenant working with the Italian ambulance service in World War I, is injured and falls in love with Catherine Barkley, the hospital nurse who tends to his wounds. He returns to the front, but a botched retreat causes him to desert the army. He reunites with the now pregnant Catherine in Switzerland. The novel ends with her death in childbirth after their son is stillborn, leaving Frederic alone.

Browsing around the Internet after finishing the novel, I came across an apparently famous 1958 interview of Hemingway in which he told George Plimpton of The Paris Review that he “rewrote the ending of A Farewell to Arms, the last page of it, thirty-nine times before I was satisfied,” explaining that he had trouble “getting the words right.”

Thirty-nine times? I repeated to myself in astonishment. Doing some research, I discovered Hemingway actually wrote forty-seven endings to that novel, ranging from a few sentences to several paragraphs, all now contained in Item 70 of the Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, Massachusetts. And for those of us not in Boston, those discarded endings are also available as Appendix II to the current Scribner edition of the novel.

A great ending, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.

As you might assume, given that the penultimate event is the stillborn birth of the baby boy and the death of his beloved Catherine, all forty-seven closers are bleak. One, entitled “The Nada Ending,” reads: “That is all there is to this story. Catherine died and you will die and I will die and that is all I can promise you.” And then there is “The Funeral Ending”: “When people die you have to bury them but you do not have to write about it. You meet undertakers but you do not have to write about them.” And then there is “The Fitzgerald Ending,” based on advice Hemingway sought from F. Scott Fitzerald. That version opens with the observation that the world “breaks everyone” and it closes with “[those] it does not break it kills. It kills the very good and very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.” There are several much longer versions that each begin as follows: “There are a great many more details, starting with my first meeting with the undertaker and the business of burial in a foreign country and continuing with the rest of my life…”

But finally, after discarding all forty-seven, Hemingway closed the novel with these three sentences, which begin with his visit to the hospital room of his dead wife:

But after I had got [the nurses] out and shut the door and turned off the light it wasn’t any good. It was like saying good-bye to a statue. After a while I went out and left the hospital and walked back to the hotel in the rain.

A great ending? Depends upon your definition. From Joan Didion’s perspective, it achieves the same level of greatness she describes in her analysis of the opening paragraph of the novel:

The power of the paragraph, offering as it does the illusion but not the fact of specificity, derives precisely from this kind of deliberate omission, from the tension of withheld information.

And certainly those last eight words of the novel—with Frederic “walk[ing] back to the hotel in the rain”—create what Didion describes as “the tension of withheld information.”

It works—I suppose. Not on my list of greatest closers, but not bad.

So what makes a great closer? As Ron Charles wrote in the February 14, 2019, edition of The Washington Post:

For the Olympic gymnast, success comes down to how well she sticks the landing. A flubbed dismount sullies even the most awe-inspiring routine.

Stock-still at their desks, novelists face a similar demand for a perfectly choreographed last move. We follow them across hundreds of thousands of words, but the final line can make or break a book. It determines if parting is such sweet sorrow or a thudding disappointment.

I agree. The best last lines stay with you long after you close the book—some like a welcome sip of fine cognac at the end of a delicious meal, and others, while not neatly wrapping up the story, stirring you to imagine what might happen next.3

So if not A Farewell to Arms, then what?

We can begin with the two great openers in American literature, whose authors also knew how to stick the landing. For that sip of fine cognac, we turn to Moby Dick and the narrator we met in the opening sentence. As we near the end of the novel, in Chapter 128 we meet the captain of the Rachel, another whaling ship. He begs Captain Ahab to help him find his son and the other men on the small whaleboat that was lost in their chase after Moby Dick. Ahab refuses, not wanting to waste time in his own hunt for the White Whale. Ahab’s pursuit ends in the final chapter of the novel with Moby Dick destroying the Pequod and killing Ahab and all of the crew except for Ishmael, who is saved from drowning by Queequeg’s empty coffin, which bobs up to the ocean surface from the sinking ship. Clinging to that coffin in the middle of the ocean for a day and a night, Ishmael ends the novel:

On the second day, a sail drew near, nearer, and picked me up at last. It was the devious-cruising Rachel, that in her retracing search after her missing children, only found another orphan.

And for the ending that stirs you to create your own narrative of what might happen next, we return to Huck Finn, who, after telling us in the final paragraph that if “I’d a knowed what a trouble it was to make a book I wouldn’t a tackled it and ain’t agoing to no more,” ends with this masterful finale:

I got to light out for the territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she’s going to adopt me and sivilize me, and I can’t stand it. I been there before.

And not wanting to fail giving Hemingway credit where credit is due, he delivered one of the most famous sips of fine cognac at the end of the novel many consider his best, The Sun Also Rises. In that final scene, Jake Barnes and Lady Brett Ashley are seated in the back of the cab:

“Oh, Jake,” Brett said, “we could have had such a damned good time together.”

Ahead was a mounted policeman in khaki directing traffic. He raised his baton. The car slowed suddenly pressing Brett against me.

“Yes,” I said. “Isn’t it pretty to think so?”

Okay, but what about other examples? Here I confess, after mulling it over, that a great ending, like beauty, is in the eye of beholder. My favorites may not be your favorites. But I will plow ahead nevertheless.

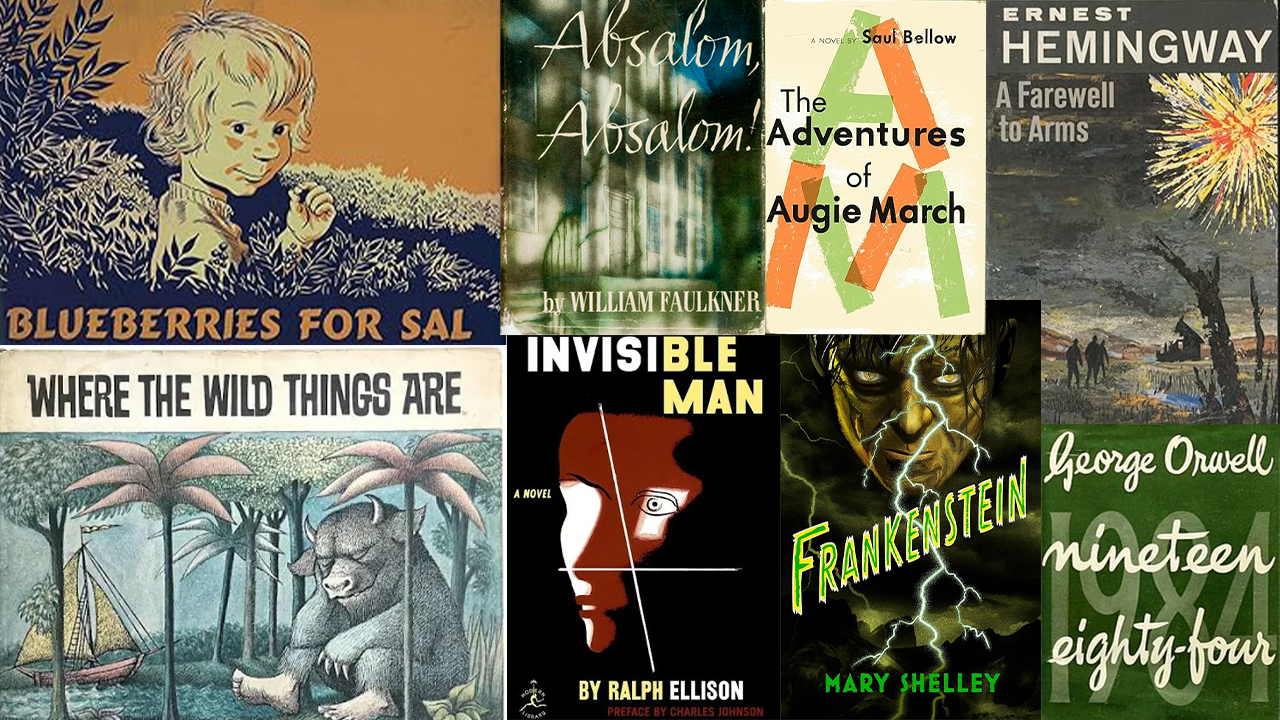

Let us start with the endings of four beloved children’s books. Each is like that sip of fine cognac—or, perhaps more appropriate here for the age of our audience, that sweet sip of Cherry Kool-Aid:

It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer. Charlotte was both.

—Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

And Little Sal and her mother went down the other side of Blueberry Hill, picking berries all the way, and drove home with food to can for next winter—a whole pail of blueberries and three more besides.

—Blueberries for Sal by Robert McCloskey

Max stepped into his private boat and waved goodbye and sailed back over a year and in and out of weeks and through a day and into the night of his very own room where he found his supper waiting for him—and it was still hot.

—Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak

But wherever they go, and whatever happens to them on the way, in that enchanted place on the top of the Forest, a little boy and his Bear will always be playing.

—The House at Pooh Corner by A.A. Milne

Then we have the short, haunting closer—perhaps more akin to a sip of fine brandy alone in a darkened room while thunderous rain drumrolls on the roof:

He loved Big Brother.

—1984 by George Orwell

“Are there any questions?”

—The Handmaiden’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Beloved.

—Beloved by Toni Morrison

Longer versions of such melancholy endings close two of the great works of short fiction of the twentieth century along with, in my opinion, William Faulkner’s best novel:

- His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

—The Dead by James Joyce

The offing was barred by a black bank of clouds, and the tranquil waterway leading to the uttermost ends of the earth flowed sombre under an overcast sky—seemed to lead into the heart of an immense darkness.

—Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

I don’t hate it he thought, panting in the cold air, the iron New England dark; I don’t. I don’t! I don’t hate it! I don’t hate it!

—Absalom, Absalom! by William Faulkner

For those who prefer an amusing sip of fine cognac at the end of a much wilder meal, here are some of my favorites:

Columbus too thought he was a flop, probably, when they sent him back in chains. Which didn’t prove there was no America.

—The Adventures of Augie March by Saul Bellow

I never saw any of them again—except the cops. No way has yet been invented to say goodbye to them.

—The Long Goodbye by Raymond Chandler

Yossarian jumped. Nately’s whore was hiding just outside the door. The knife came down, missing him by inches, and he took off.

—Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

“Good grief—it’s Daddy!”

—Candy by Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg

As you may now be starting to suspect, there are far more great closings out there than I have room to squeeze into this essay. So with a wince of regret, I will force myself to winnow my list down to just five more.

1. Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. The unnamed protagonist in Ellison’s masterpiece, an invisible Black man in a visibly White world, ends his tale with these words: “And it is this which frightens me: Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?”

I have been thinking about opening lines and closing lines since at least the day four decades ago when I started writing my first novel …

2. Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. The monster created by Dr. Frankenstein is a gentle, benevolent creature who finally gives up hope of ever being accepted by humans. On the ship near the North Pole, he vows to Captain Walton that he will burn himself on a funeral pyre so that no one else will ever know of his existence. As the Captain watches the creature drift away on an ice raft, the novel ends on this melancholy note:

He was soon borne away by the waves and lost in darkness and distance.

3. Gone With the Wind by Margaret Mitchell. The novel gives us a far more upbeat closing than one would expect from a story set during the American Civil War, complete with rape, murder, slavery, destruction, and starvation. Our protagonist Scarlett O’Hara suffers a brutal marital breakup in that last chapter when Rhett Butler tells her he no longer loves her. “What shall I do?” she pleads to him. “My dear,” he replies, “I don’t give a damn.” But the novel ends on a hopeful flourish with Scarlett’s vow to herself:

Tomorrow, I’ll think of some way to get him back. After all, tomorrow is another day.

4. Grendel by John Gardner. His novel is a retelling of the Old English poem Beowulf from the perspective of the monster Grendel. But in the novel Grendel is a sympathetic antihero who lives in isolation and loneliness with his elderly mother. In the epic final battle, Beowolf rips off Grendel’s arm, causing the monster to flee. Alone and dying, these are his final words:

“Poor Grendel’s had an accident,” I whisper. “So may you all.”

5. The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Okay, okay, okay. I realize I cannot end this without the most famous final words in American literature. This novel is the tragic tale of Jay Gatsby, the mysterious self-made millionaire and his doomed pursuit of Daisy Buchanan, an upper-class woman he loved in his youth, back before he reinvented himself as Gatsby. Toward the end of the novel Gatsby is murdered and our narrator Nick Carraway, who spent the summer around the enigmatic man, arranges a small funeral for him and then moves back to the Midwest to escape what he views as the moral corruption of the wealthy people who surrounded Gatsby. The novel ends with Nick’s somber thoughts about the death of both Gatsby and the American Dream:

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther . . . . and one fine morning—

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne ceaselessly into the past.

But I cannot end this on such a somber note. And thus a confession: I have been thinking about opening lines and closing lines since at least the day four decades ago when I started writing my first novel, The Canaan Legacy (published later in paperback under the title Grave Designs). Chapter One opens with our protagonist, young attorney Rachel Gold, having lunch at the University Club in downtown Chicago with the managing partner of the major law firm she left to form her own practice. His name is Ishmael Richardson, and thus Chapter One opens:

“Please call me Ishmael,” he said, studying the menu. “The fish here is generally quite good. I prefer the jumbo white fish.”

“Is the chef named Queequeg?” I asked.

“What’s that?” Ishmael Richardson looked up from the menu. “No,” he said, frowning. “I believe he is French. A nice chap.”

After that nod to Melville, I had to find a way to work in that final line in The Great Gatsby. The opportunity presented itself about halfway through the novel. Rachel’s brilliant, crude, and beloved colleague Benny Goldberg is driving down Lake Shore Drive with Rachel Gold and Cindi Reynolds in the back seat. Cindi is a high-class prostitute whose clientele includes many senior partners at major Chicago law firms. The following takes place as they drive:

Cindi pointed to the sailboats and yachts gently swaying in Belmont Harbor. “I once had a client who took me out on his yacht at high tide,” she said. “He paid me two hundred dollars to read him his old college girlfriend’s letters and watch him masturbate. Very strange.”

“Ah,” Benny said. “So we beat off, boats against the current, borne ceaselessly into the past.” He glanced back at me in the rearview mirror.

“Not bad,” I said. “Not great but not bad.”

Yes, but . . . I realize that great closing lines, like beauty, are in the eyes of the beholder. And thus, to mangle the closing line of Invisible Man, who knows, but that, on the lower frequencies, I do not speak for you? Accordingly, I would love to hear your picks. Please share them with me and the readers in the comments section.