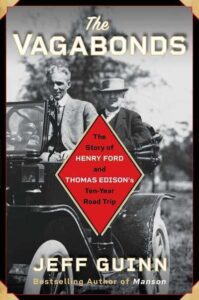

Road trips are among Americans’ favorite pastimes. Each holiday weekend millions of people “hit the road.” Jeff Guinn has reported on the inception of this traveling tradition in his latest book The Vagabonds. Guinn’s smooth, minimalist writing style chronicles the road trips taken by four American icons, Henry Ford, Harvey Firestone, Thomas Edison, and John Burroughs, between 1914 and 1924.

In only two decades—1900 to 1920— “… the number of automobiles in America had swelled from approximately 8,000 to about 10 million (2).” Cars became more than utilitarian vehicles; they were used for vacations too. “Gypsying” was the term used to describe recreational outings. Gas stations began to spring up in cities to service the horseless carriages, but backcountry travelers had to depend on the occasional single-pump grocery store for fuel.

Henry Ford achieved fame by producing and selling a car a middle-class person could afford. Every two and one-half minutes a plain black, box-shaped vehicle rolled off the Dearborn assembly line. And Ford’s radical decision to pay his workers five dollars a day made it possible for most of his employees to purchase the $500 automobile.

Thomas Edison had become America’s most recognized man after inventing several devices in his New Jersey lab. His popular inventions included the phonograph, the kinetoscope (an early motion picture device), the incandescent light bulb, and a generator to power these innovations.

The elderly, opinionated John Burroughs was known for his aviary research and had “described Ford’s brainchild vehicle as a ‘demon on wheels.’” (22) Henry Ford loved birds and wrote Burroughs a letter favorably commenting on his scientific research and at the same time offered Burroughs a free Model T. Ford, hoping that if the naturalist drove one he would change his mind about the “demon.” In Guinn’s account, Burroughs did not take to driving, but he was taken by Ford’s interest in ornithology and, little by little, they developed a deep respect for one another.

Henry Ford loved birds and wrote Burroughs a letter favorably commenting on his scientific research and at the same time offered Burroughs a free Model T. Ford, hoping that if the naturalist drove one he would change his mind about the “demon.”

Ford also realized there was an economic benefit to their friendship. “Simply by being seen out driving with Burroughs, or having newspapers take note of the outings, Ford sent a message to America. If old-fashioned John Burroughs loved to ride in them, how much more might younger, more progressive individuals savor the kind of outdoor adventures made possible by car ownership?” (23)

The joint vacationing began when Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and their families and John Burroughs stepped off the train in Fort Myers, Florida in February 1914. The trio was taken aback by all the hoopla planned for them by local officials. A parade of thirty-one cars led the band to Edison’s winter residence.

Edison, Ford, and Burroughs set out to explore the Everglades. Their initial intention was to study birdlife at Deep Lake, sixty miles southeast of Fort Myers. Much to the chagrin of the men, their wives and children joined the ornithological adventure. Outside the city, the roads deteriorated into dirt paths and deep ruts. Light rain made the tracks sticky and slippery. Upon their arrival at Deep Lake, the women noticed a plethora of snakes and insects. After a day or two of wet clothes, reptiles and bugs the entourage returned to their homes.

Firestone, whose company was the sole provider of tires for the Model T, met Ford and Edison in San Francisco on October 15, 1915, to celebrate an award Edison received at the Panama-Pacific Exposition. Thomas Edison Day was celebrated by more than 10,000 people and ended with an explosion of fireworks. The vacationers then drove one hundred twenty quiet miles on paved roads to San Diego. However, the quiet ride came to an abrupt end when they arrived at their hotel. Not to be outdone by San Franciscans, the San Diego city leaders planned their own elaborate Edison Day. It was here that the men dubbed themselves the Vagabonds and decided to annually join other gypsying Americans.

Edison, Ford, and Burroughs set out to explore the Everglades. Their initial intention was to study birdlife at Deep Lake, sixty miles southeast of Fort Myers. Much to the chagrin of the men, their wives and children joined the ornithological adventure.

So, in the late summer of 1916, Edison mapped an 1100-mile trip from his home in Orange, New Jersey to the Adirondack Mountains. This first “official” Vagabond trip was widely publicized by Edison. “We’ll steer by sun and compass only, [and] not a razor in the party… ”(67) Reporters followed their trip and Edison achieved just what he wanted. Newspapers reported the Vagabonds were just ordinary Americans on a vacation; something everyone could do.

There was no trip in 1917 because Edison and Ford were engaged in war-related work. By 1918, Edison was itching to go. He planned a trip through Virginia, West Virginia, Tennessee, and the Carolinas. The Vagabonds had fun and achieved the desired publicity about the need for better roads and more fuel stops. Guinn’s chronological report provides many detours and side trips that are intriguing. Among them is the story of Harvey Firestone’s company producing solid rubber tires exclusively for Ford cars by 1918 and, within a decade, making available bicycle-like tires for automobiles called “pneumatics.” Guinn’s writing takes other side trips to discuss Ford’s bid for the White House and to capture the industrialist’s rabid anti-Semitism.

The 1919 trip found the Vagabonds outside Troy, New York, the site of a Ford tractor plant. Publicity of this trip created more sales for cars, balloon tires, and other Vagabond products. But then, as European farmers and manufacturers restarted their businesses in the post-war economy, demand for American tires slackened and car sales slumped. Layoffs limited workers’ purchase of Edison phonographs, electric fans, and light bulbs. The 1921 trip to Yama Farms near New York City lasted only two days and this time wives were invited. No longer “roughing it” they stayed at a Ford-owned luxury resort, but the Vagabonds still met with reporters to publicize vacationing by automobile.

Firestone and Edison felt they needed a new twist to their next trip to get their desired news coverage. The tycoons invited President Warren Harding. He favorably responded and joined them at Licking Creek Camp, not far from Washington D.C. “Reporters, photographers, and ten cinematographers surrounded Harding as he genially shook hands all around.” (174) They also received wide media coverage when they arranged for a picnic with Calvin Coolidge on a later excursion.

Guinn includes many humorous and engaging anecdotes and historical kernels, but one he covers extensively occurs during a trip north. In mid-August 1923, a small fleet of vehicles stopped at a mom-and-pop grocery store in Paris, Michigan. A crowd of townspeople moseyed over to the little store curious about the fine-looking cars and the strapping chauffeurs who were taking turns fueling the cars. Someone blurted out, “That guy in the back seat looks like Henry Ford!” (3) People crept closer to catch a glimpse of him so Ford eventually stepped out of his car and acknowledged the gawkers.

Reporters followed their trip and Edison achieved just what he wanted. Newspapers reported the Vagabonds were just ordinary Americans on a vacation; something everyone could do.

Ford had stopped at this village to visit fiddler Jeb Bisbee. The manufacturer knocked on the door, introduced himself, entered the parlor, and asked Jeb to play the fiddle, accompanied on piano by his wife Sarah. Soon everyone was invited in. Before Ford left the Bisbee home, he purchased a fiddle and gave them a Model T. Thomas Edison then invited the Bisbee family to New Jersey to record their music at his studio. Soon Jeb Bisbee received dozens of orders for his fiddles and was in great demand for concerts. The Vagabonds had changed his life forever.

The ten-millionth Model T rolled off the assembly line on June 4, 1924. Two months later the Vagabonds announced their next marketing adventure: the White Mountains of New Hampshire. This venture “was altered in one significant way—they’d drive during the day, seeing interesting places and things, but utilize one inn as their nightly base.” (222) The Vagabonds and their spouses were growing older. “Instead of camps, they’d stay at the Wayside Inn in Sudbury, and, if the mood struck them, use it as a base for daily jaunts out into the New England countryside.” (223)

Jeff Guinn’s light-hearted prose takes the reader back to the early twentieth century. The book reads like a musical fugue: Its continuous theme is the annual trip; the variations, the uniqueness of each outing. The author provides colorful, insightful, and endearing portraits of the inventors and their families. His account of the early auto-camping experience coupled with the marketing savvy of Edison, Ford, and Firestone is informative and engaging, though somewhat repetitive. Guinn’s careful research of news sources from that era and his satisfying writing style capture the significant transformations taking place in America one hundred years ago due to the technological advances made by these innovators.

The Vagabonds is a mix of biography, travelogue, and relatively unknown history. Social historians, campers, automobile devotees, and naturalists will be especially fascinated by this quirky addition to the U.S. history bookshelf.

Guinn is an award-winning former investigative journalist and the best-selling author of numerous books, including Manson. He is a member of The Texas Literary Hall of Fame.