The Flame and the Arrow

Sidney Poitier as the Cold War’s Black hero.

By Gerald Early

January 10, 2022

- Oh You Kid!

I was quite young, about six or seven, when my mother took me to the theater to see Otto Preminger’s 1959 film version of Porgy and Bess. It was surely not her intention to do this, to take me to such an “adult” movie. After all, I had never heard of Porgy and Bess, knew nothing about opera, had no idea who George and Ira Gershwin were, had no idea what actors were in the movie or who they were. I thought porgies were a kind of fish my mother liked to cook. Alas, she must have had no choice. I do not remember where my sisters were but obviously my mother could not unload me on somebody, so she was forced to have me accompany her. I tried to act in a way I thought was very adult, so that she would not regret having to take me.

(As I figured out when I was older, my mother’s boyfriend bought the tickets for Porgy and Bess, surely at my mother’s insistence. Tickets had to be purchased in advance, a sign of how important a movie it was. His work schedule changed, so he could not go. Simultaneously, my mother’s babysitting arrangements fell through but she did not want to waste the tickets. Thus, I got to see Porgy and Bess.)

I was jolted by the spectacle. When the movie started, I was surprised that all the people on the screen were Black, and they were singing. I had not known that Black people could look so pretty.

At this point in my life, I had rarely been to the movies, so this was a thrill for me. Perhaps only once or twice before. (I remember well that my mother took me, intentionally, to see Ben-Hur in Atlantic City.) The size of the theater, the size of the very seat I was in, the darkness when the lights went down, the size of the screen compared to our tiny television, the fact that the movie was in color compared to a world of black and white on our home television; it all seemed glorious. I was jolted by the spectacle. When the movie started, I was surprised that all the people on the screen were Black, and they were singing. I had not known that Black people could look so pretty. It did not occur to me that the people were supposed to be poor. They looked mythical to me. This was exciting too, at first.

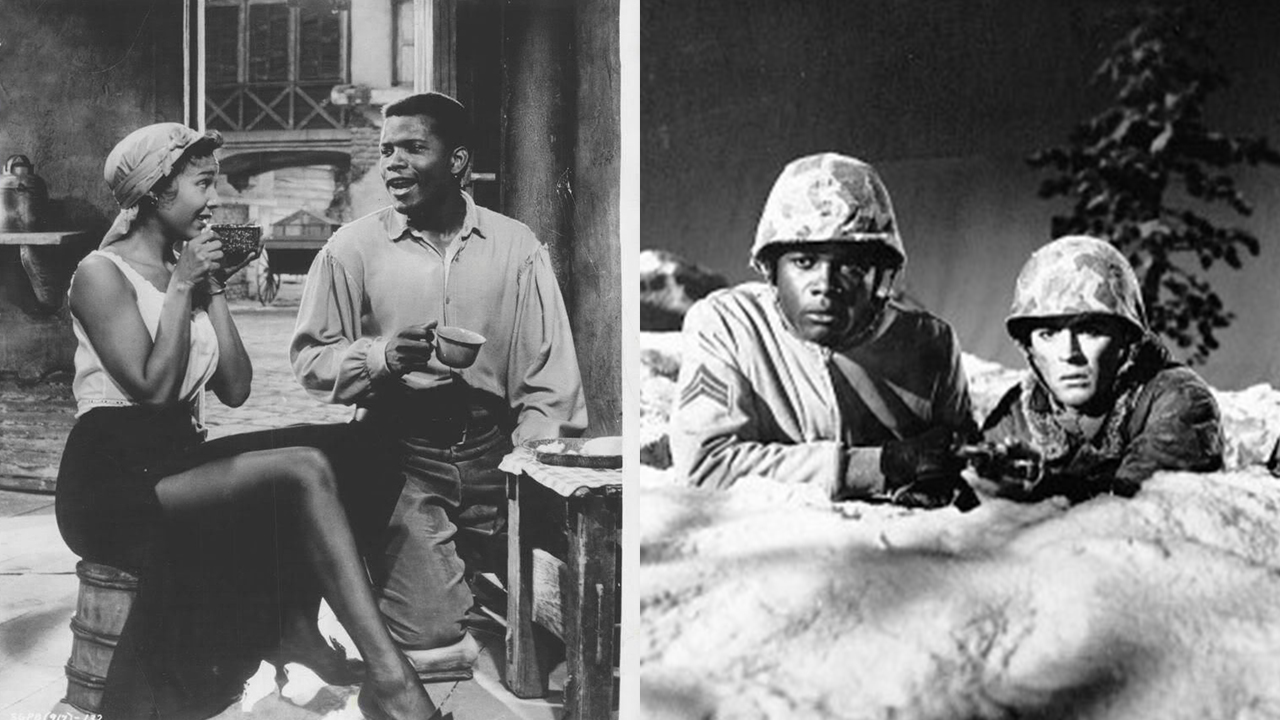

The novelty wore off, of course. I did not understand the movie at all, had no idea what the people were singing about. I ate the big box of candy my mother bought for me. The movie easily outlasted it. The theater was dark. The seat was soft. My belly was full. I fell asleep. I slept through most of the movie. This was my introduction to Black cast films. It was also my introduction to Sidney Poitier, the actor in the film my mother most wanted to see. My mother did not regret taking me. She thought I behaved well, “like a little man,” she said.

- “Out here in the fields/I fought for my meals”

The story goes like this: Harry Belafonte was first offered the film role of Porgy but turned it down. He was a natural choice as he had worked with Preminger before, playing the lead in the film version of the Black operetta Carmen Jones in 1955. The Pittsburgh Courier, one of the nation’s leading Black newspapers, reported at the time, “[Belafonte] says he’ll never play any role which demands that he spend all his time on his knees.” Belafonte tried to talk Dorothy Dandridge out of playing Bess.¹ (Hollis Alpert, in his definitive study, The Life and Times of Porgy and Bess, doubts that Belafonte was ever offered the role.²)

Poitier was offered the role but did not want it. Sam Goldwyn, the producer, was intent on getting him. Why Goldwyn wanted Poitier was simple: he was the closest thing that Hollywood had to a Black movie star and Goldwyn believed in casting his movies with stars. Poitier had proven himself in such earlier films as Joseph Mankiewicz’s hard-hitting race drama, No Way Out where he played a doctor in a White hospital, in Blackboard Jungle where he more than held his own against a cast of young actors that included Vic Morrow, Paul Mazursky, and Rafael Campos, as a good high school kid but with an attitude, in Something of Value where he played a childhood friend of Rock Hudson’s character who becomes a Mau-Mau revolutionary, and in Edge of the City, where he played good-natured dock worker who befriends John Cassavetes’s character. (I would see all these movies on television in the 1960s.)

For Goldwyn, Porgy and Bess was to be “the greatest of all his films.”³ The great American musical by America’s most accomplished composer. It was certainly going to be the most expensive Black cast movie ever made to this point. Poitier turned down Goldwyn twice. Porgy and Bess was something of a political hot potato among Black performers by the mid-1950s. It seemed dated, stereotypes abounding about Black southern life. The vice and sensuality the opera depicted was not the sort of thing Black performers wanted to be associated with. Poitier said, “there is simply one too many crap game (sic).”⁴ The Black dialect was a problem. Belafonte and his Black peers were not interested in having dialogue coaches helping them navigate a vat of “dats,” “dems,” “deses,” and “deys.” (Singer Pearl Bailey was unnerved by the word “watermelon” and ultimately had it excised from the script.⁵) For the civil rights generation of Black actors, the 1935 opera seemed a bit too tainted by the minstrel tradition—loose women, abusive men, razors, dice games, “happy dust”—even though it was conceived in part as a serious attempt to break with that tradition by showing the tragic, not comic, dimension of downtrodden Black life and the attempt to rise above it. It was certainly the most profoundly important and richly realized work of art of the twentieth century created by Whites that exclusively featured Black performers. Of course, when Sam Goldwyn tried to convince Poitier of that, Poitier thought such a view was “outrageous bullshit.”⁶ (An opinion likely shared by Duke Ellington, who also was no fan of the opera.) The only Black actor who was really eager to perform in the film version of Porgy and Bess was Sammy Davis, Jr. who was salivating over the role of Sportin’ Life. (He was afraid Cab Calloway would beat him out of the role.) Davis was the one Black actor that Sam Goldwyn did not especially want (he once referred to Davis as “that monkey”⁷) but Davis’s friends campaigned for him vigorously to get the role.

Although Poitier had not signed anything, one of Poitier’s agents had committed Poitier to Porgy and Bess without consulting him. Kramer feared a lawsuit if Poitier could not get out of his “understanding” with Goldwyn. The easiest way out was simply to do Porgy and Bess. And there it is, at least the story according to Poitier.

It must be remembered too that in the years leading up to the casting of Porgy and Bess, the winds of racial change were beginning to blow in the United States: the 1954 Supreme Court decision that declared racial segregation in schools unconstitutional; the savage, unconscionable murder of Emmett Till; the Montgomery bus boycott; the shocking White reaction to the integration of Central High School in Little Rock; the emergence of the Nation of Islam. Black militancy was pronounced. White reaction was intense and harsh. Tension was as thick as a fog.

Poitier ultimately took the role for the reason many actors take roles in films they do not like: in order to be in a film he wanted to do. He wanted to do the Black lead roles in Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones. (Another role that Sammy Davis, Jr. was dying to get.) Although Poitier had not signed anything, one of Poitier’s agents had committed Poitier to Porgy and Bess without consulting him. Kramer feared a lawsuit if Poitier could not get out of his “understanding” with Goldwyn. The easiest way out was simply to do Porgy and Bess. And there it is, at least the story according to Poitier. (Of course, there is another version of how Poitier wound up playing Porgy. Goldwyn, known for being persuasive with actors, simply talked him into it, with liberal rhetoric and money, promising not only a major production, itself a major commitment to the betterment of Blacks, but donations to Black causes, and a huge salary for Poitier. This explanation is plausible too.)

The reward for playing Porgy was not only a juicy starring role in a serious racial drama about two escaped southern convicts, one Black, one White, who are chained together, cast on equal footing with White A-list actor Tony Curtis but an Academy Award nomination for best actor to boot. This recognition did not mean that Poitier would automatically survive and thrive in Hollywood as an A-list actor. Dorothy Dandridge had been nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress for Carmen Jones (which Otto Preminger also directed) and it took her nowhere. But the nomination meant that the industry, in the liberal angst of Cold War America, thought he might possibly be their emblem of integration. He was bankable. He was marketable. And despite his protests and his discomfort, he did Porgy and Bess. So perhaps he would not be a troublemaker either. Besides, Poitier wanted a certain level of fame and glory. He wanted to get inside. He wanted what Hollywood could offer. His ambition as an actor was reasonable enough, and the industry counts on the fact that no actor wants to hustle endlessly for his meals. There comes a time when you want the roles you want to come to you. With Porgy and Bess, Poitier was getting a taste of that with a role he did not want. But in exchange, he got the role he wanted. That was not a bad trade. Locked between two forms of White liberalism—the paternalism of Goldwyn and the integrationist politics of Kramer—it is something of a marvel how adept Poitier was at managing both.

Understanding Black ambition is not always an easy thing for this country to do; sometimes it is not an easy thing for Black people to do. Because of a morass of legal issues involving the Gershwin estate, the film version of Porgy and Bess has rarely been seen since its initial release, is not on DVD, likely never will be, and is not known by the general public. (Inferior bootleg versions can be found here and here.) It did not hurt Poitier much, in the long run, to have been in it. Moreover, Porgy and Bess was by no means the worst film he starred in. I reserve that dubious distinction for The Long Ships, a 1964 film where Poitier played a Moorish prince (wearing a terrible wig that looked very much like a bad version of a Little Richard pompadour). I was twelve at the time and eager to see the film, as were my Black friends, as we thought Poitier was going to play some sort of Tyrone Power- or Errol Flynn-type hero. We could not have been more wrong. We did not know he was supposed to be the villain! We thought he got cheated out of being the hero he was supposed to be. No The Flame and the Arrow- Burt Lancaster-ish heroics for Poitier here. It was one of the most racist movies I ever saw. Poitier’s character was completely emasculated and humiliated. The White hero (Richard Widmark as a Viking) not only steals Poitier’s wife (in whom Poitier never expresses a sexual interest in, probably because she was White and the thought of coitus between them had to never enter the audience’s mind) but conquers him in the end. Poitier said the film served as “a constant reminder that I must never let my head get too big.”⁸ I was so disappointed that I nearly cried when I left the theater. It was as bad as seeing a jungle movie with the African “natives.” If Poitier could not be a Hollywood-style hero, what other Black actor at that time could? But Poitier was a big enough star by 1964 that his career could survive this fiasco. I learned from this as a boy a tough lesson: that movies can break your heart.

His ambition as an actor was reasonable enough, and the industry counts on the fact that no actor wants to hustle endlessly for his meals. There comes a time when you want the roles you want to come to you. With Porgy and Bess, Poitier was getting a taste of that with a role he did not want. But in exchange, he got the role he wanted. That was not a bad trade.

Poitier’s biggest concern about playing Porgy was what would Paul Robeson think. Robeson was the Black actor that many Black actors were trying to emulate, perhaps in ability, but especially in attitude, in racial consciousness, in the willingness to sacrifice a career in the fight against Jim Crow and racism. In this regard, Poitier took a role that Robeson himself had turned down years earlier. “[George] Gershwin had offered Robeson the part of Porgy and told him he was ‘bearing in mind Paul’s voice in writing it.’”⁹ That had to be on his mind. “Like Harry Belafonte, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, and others, Poitier admired Robeson’s fearless political conscience. He and Belafonte often accompanied Robeson on long walks through Harlem or joined him at a Fifth Avenue bar off 125th Street, where they gobbled up Robeson’s revolutionary rhetoric and pitched him ideas.”¹⁰ Whatever Robeson was, Poitier was not going to be that. Besides, Robeson had done his share of compromised movie roles. If anyone could understand how Poitier got manipulated by White power and his own ego into doing Porgy and Bess, it would certainly have been Robeson.

- Manchild in Wonderland

Think about it, Gerald. In the 1950s, you saw the rise of the dark-skinned Black man in American popular culture: Jackie Robinson, Miles Davis, Nat ‘King’ Cole, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Sidney Poitier. That ought to tell you something.

—A conversation I had with the late Stanley Crouch

What a difference a year makes! In 1960, my mother took me and my sisters to see a Sidney Poitier film called All the Young Men, a Korean War drama. (The Korean War was the first war we fought with an officially desegregated military thanks to President Truman’s 1948 executive order, an important fact to know to understand this film.) As I was watching it, I had no idea that this was the same actor I saw in Porgy and Bess. Naturally, this film, about conflict, combat heroism, chivalry, patriotism, and leadership, was more appealing to me as a boy than it was to my sisters and obviously more appealing than Porgy and Bess, which I did not even understand. Unlike Porgy and Bess, Poitier was the only Black actor in All the Young Men, and this was to be the template for the heyday of his film career, a Black person mostly surrounded by Whites.

(This formula worked well for him—he won his Academy Award for Lilies of the Field, where he played a handyman who helps a group of German nuns build a chapel—until the late 1960s when Black Power and anti-integrationist aesthetics dominated Black thinking and this sort of hero was no longer acceptable. Black performers like Sammy Davis, Jr., Jimi Hendrix, Poitier, Johnny Mathis, the Supremes of Motown—all integrationist inspired—adjusted to this profound shift but it cannot be said that were no adverse effects for them or that they were made truly “authentic” by the change. Authenticity was the thing, as the existentialists used to say, and for Blacks by the late 1960s the turn was from what is now called respectability politics to the cult of criminality—the criminal as hero and artist; crime as creative resistance. The late Stanley Crouch told me that the Black bourgeoisie and Black intellectuals had become infected with what he called “the Romanticizing Macheath Syndrome.”)

Unlike Porgy and Bess, Poitier was the only Black actor in All the Young Men, and this was to be the template for the heyday of his film career, a Black person mostly surrounded by Whites.

In All the Young Men, Poitier was a tough Marine sergeant who was placed in charge of a small company by the dying White lieutenant, over a more experienced White sergeant played by Alan Ladd. (Ladd had been a major star in the 1940s and 1950s, starring in Shane, considered by many one of the finest westerns ever made. By 1960, his day was done. It was a sign of how each actor’s fortunes were tending that they were given equal billing. Poitier’s star was definitely rising.) One member of the company (played by Paul Richards) is an outright racist who sows seeds of doubt about Poitier’s character’s ability. It is, in its way, a film that anticipates the drama over Affirmative Action. Poitier, as it turns out, is better than any man in his company, smarter, braver, tougher.

I loved the movie. I absolutely adored Poitier’s character. I went back by myself to see the movie again. I now knew who Sidney Poitier was and I would, for years after, see any movie he was in. I wanted to walk like Poitier, talk like Poitier, act strong and dignified like Poitier. Because he was from the Bahamas, although born in America, and my mother’s father was a Bahamian, I felt an even deeper connection to him. All the Young Men became my equivalent of Burt Lancaster’s The Flame and the Arrow, the Black boy’s fantasy movie about an impossibly heroic person, an impossibly competent person, who fights for king and country. Poitier’s character made me proud to be an American, made me feel as if I was an American without any hesitation or crippling doubt. The movie had more “swashbuckling” than a Black hero had ever done before. The only thing that was missing was that Poitier did not get the girl. He could have been given a girl. I knew White heroes in war movies got the girl even in the most contrived ways. But Poitier was still everything for me. In the years that followed, for most of the decade of the 1960s, whether I liked or disliked his movies, Poitier was this one thing for me: The Flame and the Arrow in American films.

1 Aram Goudsouzian, Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 149.

2 Hollis Alpert, The Life and Times of Porgy and Bess: The Story of an American Classic, (New York: Knopf, 1990), 260.

3 Alpert, The Life and Times of Porgy and Bess, 260.

4 Goudsouzian, Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon, 149.

5 Alpert, The Life and Times of Porgy and Bess, 262.

6 Goudsouzian, Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon, 150.

7 Goudsouzian, Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon, 151.

8 Goudsouzian, Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon, 221.

9 Martin Bauml Duberman, Paul Robeson, (New York: Knopf, 1988), 193.

10 Goudsouzian, Sidney Poitier, Man, Actor, Icon, 88.