The Content of Our Caricature: African American Comic Art and Political Belonging; Invisible Men: The Trailblazing Black Artists of Comic Books

Comics are a tricky art form. Novelists and memoirists can use as many words as they need to convey meaning; painters, working in a purely visual medium, are not obligated to say anything in the literal sense. Comics, though, have limited space for words and pictures to work together in getting messages across. The miracle of great cartooning, then, occurs when the enormity of what is conveyed—often through suggestion—belies the space in which it is contained. On the flip side, comic strips and comic books whose messages seem commensurate with the limited size of the panels are often dismissed as works for the unsophisticated; and historically, in a form that dates back to the nineteenth century, many comics have been exactly that. In recent decades, works as different as Marvel Comics titles, Aaron McGruder’s The Boondocks, and the explosion of graphic novels and memoirs, with Art Spiegelman’s Maus as their standard bearer, have won a measure of respect, and certainly Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts has been the object of intellectual analysis worthy of a Dostoevsky novel. But what often goes overlooked in even the most seemingly simple-minded comic books and comic strips is that they do not draw themselves: they are almost always the work of skilled artists who have, historically (this applies particularly to comic books), often worked in near or total anonymity.

Add race to the story of comics, and things get very interesting indeed. One of the more astounding features of Black life in America is that despite often steep odds, any field one cares to name will turn out to have at least a few Black people—frequently more than that—working away in it. Comics are no exception. Two new books, in many ways vastly different, take on the history of Blacks in American comics—one discussing the work of more celebrated cartoonists of the last century or so, the other focusing on previously hidden figures.

The miracle of great cartooning, then, occurs when the enormity of what is conveyed—often through suggestion—belies the space in which it is contained.

In the brilliant, fascinating The Content of Our Caricature: African American Comic Art and Political Belonging, Rebecca Wanzo, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, looks at representations of Blacks in comics and cartoons beginning in the nineteenth century. Among the major questions she explores are how comic art has contributed to the discussion of Black American citizenship and whether and how stereotyped images of Blacks can be successfully turned on their heads for positive, incisive expression. In their early days, cartoons were a weapon in White supremacists’ arsenal; as Wanzo notes (7), “Racist caricature was . . . not a side note to US cartooning’s emergence. It was central to it.” Central to Wanzo’s thinking about work by Black cartoonists is that it responds, whether or not willingly, intentionally, or even knowingly, to historical White racist images of Blacks. Wanzo’s book is an examination of how Black comics have done so—and how they have reflected and commented on the place of Blacks in America.

An early example is the peculiar case of George Herriman. Herriman was designated as “colored” on his birth certificate but passed for White most of his life. He is best remembered as the creator of Krazy Kat (1910–1944), a comic strip as deeply strange as it is celebrated. Krazy Kat depicts a world in which animals talk and the natural order is reversed: the black cat of the title is in love with a mouse, Ignatz; Ignatz loves to hurl bricks at Krazy, which the cat not only does not mind but seems to feel is the fulfillment of their relationship; and a dog, Officer Pupp, has kindly feelings toward Krazy and tries to keep Ignatz in line. Herriman wrote and drew other works as well, including a short-lived strip called Musical Mose, whose title character is a jet-black African-American with white, monstrously large lips. One six-panel strip from 1902, titled “Musical Mose Tries Another ‘Impussanation,’” and reprinted in Wanzo’s book, finds Mose playing music at an Irish celebration, which goes well until several of the attendees decide to beat Mose to a pulp. In the last panel, Mose, at home, pens a declaration that “de Irish an me has nuffin to do wif each other any mo,” while his wife advises him to stick to “cullud” events. While some have expressed the view that the strip simply reflects the typical, racist humor of the time, Wanzo argues (34), “Herriman was aware that discovery of the designation on his birth certificate would almost certainly destroy his career with not only William Randolph Hearst’s papers but any other paper in the white world. Autobiographical criticism invites us to understand the strip as a violent illustration of the risks and potential costs when black people attempt to assimilate—even when their skills and abilities should create the conditions for acceptance.” She further maintains that even Krazy Kat “can be read as speaking to issues of identity, rejection, and resilience.” (34)

Central to Wanzo’s thinking about work by Black cartoonists is that it responds, whether or not willingly, intentionally, or even knowingly, to historical White racist images of Blacks.

In stark contrast to Herriman’s work—and representing societal progression in thinking on race—is Sam Milai’s. For over three decades, Milai, a Black man who presented as such, was an editorial cartoonist for the Pittsburgh Courier, which at the height of its influence was one of the most prominent African-American publications in the nation. Milai too, Wanzo argues, engaged in Black stereotype, but for reasons that were vastly different from Herriman’s and that, ironically, had everything to do with the politics of respectability. One Milai cartoon is titled “Racists, Back to Back . . . Cause and Effect!” The cartoon was published in 1968, as the nonviolence-oriented protests of the civil rights movement were giving way to riots and calls for Black Power. It depicts two figures standing back to back—the implication being that they are supporting each other—even as they turn their heads to glare at each other with contempt and suspicion. One is a paunchy White man in a cowboy hat, holding a big stick in either hand, one labeled “Bigotry,” the other “Racism”; the other is a slim Black man with a handkerchief tied around his head and a Molotov cocktail in either hand—one labeled “Hate,” the other “Resentment.” In the background are smoldering ruins of a neighborhood, understood to be the result of the two men’s work.

Published in the same era as Milai’s cartoon, Tom Floyd’s Integration Is a Bitch! (1969), a book of one-panel strips, also employs the stereotype of the angry/violent Black man—but, again, for very different purposes. The book’s central character is George, who goes to work in an office where he is evidently the first Black employee. The panels follow George as he endures what would today be called microaggressions, until, in the climactic panel, he stands on a desk and shouts “Black Power!” while the Whites sitting at desks around him wear expressions of bewilderment, obviously without a clue as to what is upsetting their co-worker. Unlike Milai’s cartoon, Floyd’s work sees Black rage as an inevitable, even healthy response to White racism; but like the work of Milai, Herriman, and others, it can be read as a comment on the place of Blacks in American society. “The foundation of black citizenship,” Wanzo writes, “is noncitizenship.” (25)

That idea extends to comic representations of childhood. Wanzo maintains that while many comics featuring White children romanticize childhood innocence, Black kids in comics “are often presented as outside of innocence and something other than children” (139), both by White cartoonists who stereotype Black kids (for example, Richard Felton Outcault, creator of The Yellow Kid, the first recurring character in newspaper strips) and by Black cartoonists who employ this notion for their own ends. Three prominent examples of such Black cartoonists are Ollie Harrington, creator of the strips Bootsie (1936–1974) and Dark Laughter (1938–1956); Brumsic Brandon Jr., creator of Luther (1969–1986); and Aaron McGruder, creator of The Boondocks (1996–2006). In a Luther strip (reprinted in Wanzo’s book) from 1971, when the Vietnam War was still raging, a White child tells two Black kids over the course of three panels, “It’s stupid to blame hunger on the war! My father said this country is rich enough . . . to have both guns and butter!” In the final panel, in one of those miracles mentioned earlier, one of the Black children looks up at the older title character and asks, “What’s butter, Luther?”

Wanzo discusses other comics that follow the notion of Black violence to its logical end—such as the graphic novel Nat Turner (2005) by Kyle Baker (“arguably the most successful and prolific cartoonist I discuss in this book,” 84); comics that put the notion of Black citizenship front and center, such as the series Truth: Red, White & Black, written by Robert Morales and illustrated by Baker; and comics that aggressively, and with uninhibited use of stereotype, flout the politics of respectability, such as Kelly Sue DeConnick and Valentine DeLandro’s Bitch Planet. Wanzo concludes, “I cannot imagine a time free of some version of black representation that can be read as caricature. Because on some level, its absence will always be a sign of forgetting the monstrosity crafted by historical injuries, a weight carried by all black people perpetually in the wake—and on the brink—of real political change.”

• • •

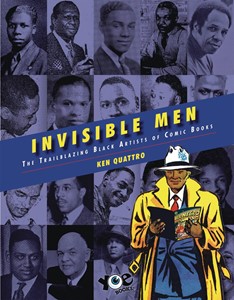

Wanzo writes with the seen-it-all air of one who is unlikely to be surprised by anything you could tell her about race and racism. (She is also an incurable academic; ten-dollar words such as “diegetically” and especially “hermeneutic” abound, as well as more instances of “affective” than you could shake a fountain pen at.) By contrast, Ken Quattro, author of the eye-opening, doggedly researched Invisible Men: The Trailblazing Black Artists of Comic Books, writes rather endearingly as one who is discovering along with (some) readers the circumstances faced by the Black illustrators he profiles. “I didn’t know how ignorant I was until I began this project,” he writes. (9) “Much of what I learned came from Black publications, as contemporaneous White ones didn’t carry the information I sought. I learned who Miss Ann and Mister Charley were, and what an ofay is.” Quattro’s website calls him “The Comics Detective,” and it is easy to picture him square-jawed with a fedora and trench coat like Chester Gould’s comic-strip detective Dick Tracy, with a tough exterior and tender heart—or like Ace Harlem, a Black gumshoe likely modeled on Gould’s creation—as he unearths these stories.

Invisible Men comprises mini-biographies of men who, unbeknownst to the general public, worked as illustrators during the flowering of comic books’ popularity in the early and middle years of the twentieth century. While racism might have kept these men out of the industry altogether as it did with many other lines of work, two developments cleared the way for their participation. One was World War II, which saw many White artists heading off to war and leaving comics publishers in the lurch. The other was the birth of comic shops, which were independent of comic book publishers but supplied art for them. The shops “were, by definition, art studios, but in practice they more closely resembled the production lines of Henry Ford,” Quattro writes. (36) The comic shops often served as buffers between the Black artists and the publishers who might well have refused to hire them directly. “It was a common practice for publishers and shop owners to demand anonymity of their artists, who would change frequently, so that a false continuity could be presented to readers,” Quattro notes. (38) (A side note: one publisher who did frequently employ Black artists was Stan Lee of Timely Comics, the forerunner of Marvel.)

Invisible Men comprises mini-biographies of men who, unbeknownst to the general public, worked as illustrators during the flowering of comic books’ popularity in the early and middle years of the twentieth century. While racism might have kept these men out of the industry altogether as it did with many other lines of work, two developments cleared the way for their participation. One was World War II, which saw many White artists heading off to war and leaving comics publishers in the lurch. The other was the birth of comic shops, which were independent of comic book publishers but supplied art for them. The shops “were, by definition, art studios, but in practice they more closely resembled the production lines of Henry Ford,” Quattro writes. (36) The comic shops often served as buffers between the Black artists and the publishers who might well have refused to hire them directly. “It was a common practice for publishers and shop owners to demand anonymity of their artists, who would change frequently, so that a false continuity could be presented to readers,” Quattro notes. (38) (A side note: one publisher who did frequently employ Black artists was Stan Lee of Timely Comics, the forerunner of Marvel.)

Invisible Men comprises mini-biographies of men who, unbeknownst to the general public, worked as illustrators during the flowering of comic books’ popularity in the early and middle years of the twentieth century.

As different as Quattro’s book is from Wanzo’s, it does present one figure whose path has striking similarities to George Herriman’s, as Wanzo depicts it. Born in 1899 in Charleston, South Carolina, Adolphus Barreaux Gripon came from a family designated as “mulatto.” At fifteen, struck by typhoid, he moved with his family to New York City for the less humid climate. From that point on, the family passed for White, and as if to mark the change, Gripon began using the name Adolphe Leslie Barreaux. Launching a career as an illustrator, he contributed to comics including Sally the Sleuth, whose buxom title character—like the vast majority of comic book characters—was White. (The other illustrators profiled in the book presented as Black.)

And if Kyle Baker is the star of Wanzo’s book, the corresponding figure in Quattro’s is another Baker. Clarence Matthew Baker, known as Matt, was so talented that his “artwork, particularly on covers, was a game-changer for the comic book industry. He was widely copied,” as Quattro notes. (133) Baker was possibly unique among Black illustrators in that he worked in-house for publishers, alongside White artists, who respected him. Among other characters, he drew Voodah, “the first Black hero to be given his own feature in a White comic book,” according to Quattro. (131) Invisible Men details other firsts: for example, Elmer Stone drew a story for the inaugural issue of Detective Comics (the series that launched Batman) in 1937, which “would likely make him the first openly Black artist to work in the comic book industry” (35); Wonder Woman # 13 (1945) featured the first comic book story that was about a Black person (Sojourner Truth) and also drawn by one (Alfonso Greene); Eugene Bilbrew and Bill Alexander created The Bronze Bomber, which according to more than one source was the first Black superhero; and the short-lived Negro Heroes (1947–48) was “the first attempt by any publisher to address the Black readership.” (210) That was soon followed by All-Negro Comics, which included John Terrell’s Ace Harlem.

Invisible Men includes reproductions of the artists’ work, most of them in full color. These comics, in the main written by others, are not stories for the ages. The artwork was the best part of these books, which the public happily purchased, with no understanding of what it held in its hands.