The Black Man behind the Curtain of the Rush Limbaugh Show

“Bo Snerdley” remembers Rush Limbaugh and his own career in radio.

By Gerald Early

March 29, 2022

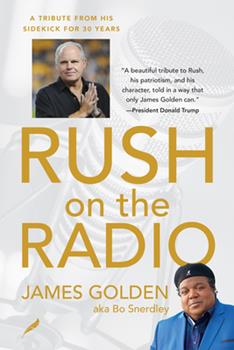

Rush on the Radio: A Tribute from His Sidekick of 30 Years

As a Black guy, a proud African American, it always infuriated me to hear my friend [Rush Limbaugh] called a racist. Rush didn’t have a racist bone in his body. He wanted his staff to be excellent, so he hired excellent people. It just so happened we had a very diverse staff: gay, straight, Black, white, Asian, it didn’t matter, as long as you were good at your job.

–James Golden, Rush on the Radio, (183)

1. Among the conservatives

I had known for some years, probably since 2010, that I wanted to develop some courses on American conservatism. The reason was, in part, to understand America’s culture wars better by learning more about the side I knew less well. Also, I suppose I wanted to understand my past, for I grew up among urban working-class people, Italian and Black, who were, in different but compelling ways, conservative. That is, they strongly disliked or distrusted White liberals, but from very unlike perspectives. (There is, at the root of it I suppose, a certain unsuspected sentimentality that governs what we want to know and how we want to know it.) Finally, I thought our students might benefit by reading conservative arguments without any filter of liberal or leftist interpretation or disapproval. I asked the late Henry Berger, WU history professor, what he thought, and he enthusiastically encouraged me to do this. He thought it would be good for the students but, more importantly, he thought it would be good for me. Never let an academic itch go unscratched, or something like that.

In the end, for American Culture Studies, I taught “The Cultural History of American Conservatism from Herbert Hoover to George Will” in spring 2015, “The Making of American Conservatism since 1932, from Hoover to the Tea Party” in fall 2016, “The Making of American Conservatism since 1932, from Herbert Hoover to Donald Trump” in fall 2017. All of these were the same course with slightly different titles. For African and African American Studies, I taught “Black Conservatives and their Discontent: African Americans and Conservatism in America” in the fall of 2020. This last was probably the course I wanted very much to teach above the others, although I enjoyed teaching all of them and learned a great deal. The Black students I had in my Black conservatives course (and only Black students enrolled in it) may have disagreed with a lot of what they read, but it was not at all alien to them. They had heard some of the Black people around them say versions of some of what they read. They had even thought of it themselves, especially in regards to affirmative action, about which they expressed ambivalence. This familiarity did not make the texts endearing but the students did conclude that Black conservatism was not the same as White conservatism.

In preparing to teach these courses, I had to learn the world of the conservatives not just by reading their books but also by attending rallies. I remember once attending a Tea Party rally with my daughter, Rosalind, who was afraid we would be physically attacked because of our race. It is true that this rally—which featured speeches by Sarah Palin and Glenn Beck and an Honor Guard, no less, for the Pledge of Allegiance—had, in addition to me and Rosalind, only three or four other Black people that I could spot in attendance of what was probably an audience of possibly a thousand. I told Rosalind that nothing would happen to us. Nothing did. In fact, we were treated like the prodigal son, come back to his father. The attendees were extremely nice to us, invited us to other Tea Party events, were actively recruiting us as like a proselytizing church desperately seeking members. As I told Rosalind, “They’ve been converted in spite of themselves. They think diversity is valuable too.”

The Black students I had in my Black conservatives course (and only Black students enrolled in it) may have disagreed with a lot of what they read, but it was not at all alien to them.

An essential part of the world of the conservative is talk radio and the prince of conservative talk radio was Missouri native son Rush Limbaugh. I had, over the years, heard snippets of his show, twenty minutes here, ten minutes there, if I had the radio on while driving or something like that. I was a bit daunted by the idea of listening to Limbaugh (or anyone, for that matter) talk for three hours a day but I had to understand his appeal and also needed to know exactly what he said. (My mother loved Black talk radio when I was a kid, so I had some tolerance for yakking.) There was, further, the concern of being over-saturated by someone else’s political pieties that might make me more sympathetic to them than I should be, not for the sake of the integrity of my own views but more for my ability to teach with intellectual dispassion. I did not want to feel that I had to defend something simply because, like a biographer, I had, inadvertently, unconsciously, fallen in love with a discourse I had invested so much time trying to unravel. No self-generated brainwashing!

In any case, I began to listen to the show three hours a day, five days a week for many weeks, actually months, on and off for several years. It was an interesting job. I learned five things doing this: 1) Limbaugh was, at times, a good satirist; 2) Limbaugh made enormous amounts of money, a fact he shared constantly with his audience, and his audience was proud of his success and felt he deserved it; 3) From time to time, Limbaugh gave away prizes to lucky members of his audience that were generous; 4) Limbaugh’s show was carefully structured and I could understand why his fans found it so informative and entertaining but I could also understand why he was intensely hated; 5) Limbaugh’s call screener, whom he called “Bo Snerdley,” and whom he talked about more than any of his other staff—all of whom he did mention from time to time—was a Black man, a point that Limbaugh emphasized when talking about him. He became a character at times in Limbaugh’s shows, for instance, during the Obama years, called “an official Obama criticizer.” (77) That interested me greatly.

2. The Golden Gate to conservatism

The Show is the thing.

—Rush Limbaugh

James Golden met Rush Limbaugh in the summer of 1988 when Limbaugh, fresh from Sacramento, arrived at WABC, the biggest radio station in New York, to do a mid-day radio show. At first, no one gave the show much of a chance. As Golden explains, “… most listeners tuned in during morning and late-afternoon drive times.” (20) Limbaugh put it this way, “We were going to syndicate a national program in the daytime without local issues without local phones numbers and so forth, and nobody in the business thought it would work.” (21) When the two met, Golden had been in radio for nearly twenty years, getting his first job in the medium at the age of seventeen, largely foregoing a career as a musician, a smart move as he suffered from performance anxiety. Golden had worked in both Black and White radio, in both music and talk radio, and had risen to be program director at WABC. Before Limbaugh, he had worked as the producer of Alan Colmes’s radio show, before Colmes went on to be the liberal half of Fox News’s “Hannity and Colmes.”

Golden was immediately struck by Limbaugh; by his confidence. He jokingly told Limbaugh that he would be the new Paul Harvey. Despite the teasing, he did think Limbaugh was different. He also thought if anyone could succeed at having a successful national mid-day conservative radio talk show, Limbaugh might. As soon as Golden heard Limbaugh, he liked the show, “the attitude, the humor, and the smart takes on taboo issues.” (22) Before the summer was over, Golden was working for Limbaugh. He explains how he became “Bo Snerdley”:

Because we worked in the same building, I’d sometimes bring him unusual news stories that I thought he’d appreciate, and that’s how we first got to know each other.

WABC provided a call screener and an engineer for the program. One of the first was a woman who didn’t want her friends to know she was working with a conservative show, so Rush called her Marva Snerdley. And there were other Snerdleys in the radio family. Even then, being known as a conservative was not always socially acceptable….

About two months after the program’s launch, “Marva” moved on to a different show and I gladly stepped into the role. I’ll never forget the day I walked into Rush’s studio as an official part of the team. There was (sic) just five minutes before the show began. “Well, James, you know everybody on the show’s gotta be a Snerdley. Which Snerdley are you?”…

The Daily News had a story about Bo Jackson the baseball player. “Uh. Bo!” (22)

Being a call screener for Limbaugh was not easy. Golden had to make sure he was funneling the right callers Limbaugh’s way, callers that Limbaugh could use effectively to keep his show interesting. As Golden writes, “Call screening can be a tough gig, if done correctly. At the end of three hours, you feel like you’ve been through the wringer—because putting other people through the wringer is hard work! In a typical day, I may have spoken with a hundred people, and only five of them might make it on air.” (23) As Limbaugh himself characterized call screening: “People don’t understand the call-screening process and how important it is to a show like that that doesn’t take very many. … It’s one of the key elements of the program that few people understand. It can’t be done by everybody.” (110–111)

Limbaugh started out with a two-hour show, but it quickly moved to three because of the ratings. He began in August 1988 with fifty-six and within three months was airing on over one hundred. In two years, it would be six hundred. Limbaugh was a staggering success. By the time he died in 2021, Limbaugh had an estimated audience of 27 million listeners, possibly more. But it is a mistake to say Limbaugh was simply some right-wing ranter who gathered all the right-wing nutjobs around him. There have been right-wingers on the radio since the 1950s who never came close to Limbaugh’s success. Limbaugh was the biggest talk phenomenon to hit radio since Father Coughlin of the 1930s. Unlike Coughlin, Limbaugh was not anti-Semitic. But he could mobilize his audience as Coughlin did. Golden notes Limbaugh’s attributes in explaining his success: “He had the cadence of a Top 40 disc jockey, the authority of a newscaster, the coolness of an FM announcer, and the humor of the best morning or afternoon hosts in the business.” (231)

Being a call screener for Limbaugh was not easy. Golden had to make sure he was funneling the right callers Limbaugh’s way, callers that Limbaugh could use effectively to keep his show interesting.

Golden makes a point that it was not simply the size of Limbaugh’s audience but its loyalty that made Limbaugh unique as a celebrity and a political pundit/entertainer. This loyalty, according to Golden, is why the liberals’ attempts to cancel him, and there were many, failed. Limbaugh would be accused of being a racist, a sexist, a homophobe, a climate change denier—you name it, (some of these accusations he purposefully courted because provocation was red meat for his listeners)—and liberals would threaten Limbaugh’s sponsors with a boycott and protests. Invariably, armies from Limbaugh’s massive audience would simply overwhelm any liberal protest, would buy out the products of a company threatened with a boycott, or threaten one of their own if the company dropped Limbaugh’s show. Their power thwarted the liberals at every turn. He was the most successful troll in popular culture who ever confronted liberal and leftist opinion.

But he had his moments of vulnerability. The closest Limbaugh came to being canceled and driven off the air was in February 2012, after responding to Georgetown University law student Sandra Fluke’s congressional testimony urging federal health care provisions to cover the cost of contraceptives given the hardships of some of her fellow law students. In a satirical bit that outran its satire and simply became an insult, Limbaugh called Fluke a “slut” and “a prostitute.” The liberal outcry was deafening. Even Republicans denounced him. This time, he began actually losing sponsors. I remember listening to his show during this controversy: he was almost begging his audience not to desert him. It was the only time I can recall when he actually sounded desperate but nonetheless petulantly defiant. There were moments when I thought he sounded self-pitying, contrite, uncertain about his future. He apologized to Fluke, who did not accept it. But once again his audience rallied to his support, so massive and so loyal that he could weather losing sponsors, and he survived. Golden does not mention this incident in his book. I wish he had.

Golden disagrees with Black Lives Matter, Critical Race Theory, the 1619 Project, and the like but not quite for the same reasons that White conservatives do.

Golden’s book tells the story of his relationship with Limbaugh, with whom he worked for nearly thirty years, providing a behind-the-scenes look at how the show was put together and the personalities who worked as part of Limbaugh’s staff. He evaluates Limbaugh’s guest hosts, discusses Limbaugh’s loss of hearing (which came closer to driving him off the air than any liberal protests), and Limbaugh’s drug addiction, caused by Limbaugh’s anxieties and insecurities. In the early years of his national show, Limbaugh was distressed by the number of people who hated him. “I had to learn—which was a tough psychological thing for me—I had to learn how to take being hated as a measure of success. Nobody’s raised for that.” (263)

Integrated into this flattering memoir of Limbaugh is Golden’s autobiography, his adventures in radioland as a data analyst, a producer, a call screener, and an on-air personality. The reader learns a great deal about how a career in radio works. The book also devotes considerable space to Golden’s political views as a Black conservative which, he said, he did not realize he was until he started working for Limbaugh and found himself agreeing with much that Limbaugh said.

But he makes it a point that he is a Black conservative. He talks about his differences with Limbaugh, how Limbaugh respected and understood those differences (celebrating the Fourth of July, for instance). Golden disagrees with Black Lives Matter, Critical Race Theory, the 1619 Project, and the like but not quite for the same reasons that White conservatives do. And there were sharp differences: he thought Derek Chauvin was guilty of murdering George Floyd and convinced Limbaugh of this. (I heard the programs where Limbaugh discussed the Floyd killing and he did indeed characterize it as murder, in contrast to much of his audience.) Golden criticizes the Republican Party for not offering more solutions in place of mere opposition and for not trying more vigorously to get Black voters. The chapters where he relates his discussions with Limbaugh about race are probably the most valuable. The chapters dealing with Limbaugh’s illness and death are moving—even if the reader hates Limbaugh’s guts—because Golden is so deeply affected by how unexpected it was and how Limbaugh dealt with it. The relationship between the two men, who upon first meeting had only a love of radio in common, is compelling.