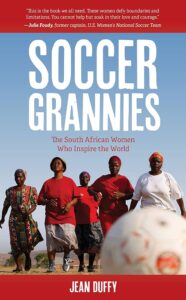

For a feel-good story shaped by a love for sports, look no further than Soccer Grannies by Jean Duffy. This story is an antidote to the ugliness behind so many international sporting institutions and events, from the well-documented human rights violations of the International Olympic Committee to the corruption of FIFA and FIBA. This story reminds the reader of what is possible when groups of people who are separated by oceans, continents, and lived experiences share a love for the same sport.

Jean Duffy is a nonfiction writer and an adult amateur soccer player. In early 2010, a woman from a team called Lexpressas emailed her a video about a soccer team from rural South Africa made up entirely of grandmothers. Duffy, a self-described sucker for human interest stories, was hooked right away on the Soccer Grannies, whose official football club name is Vakhegula Vakhegula, which means Grannies Grannies in the team’s native language of Xitsonga. Duffy’s aptitude as a storyteller and her love for soccer made her a good fit to pursue the story of the Soccer Grannies, eventually creating strong bonds with the women on the team, inviting them to her hometown of Lexington, Massachusetts, and visiting them in their home village of NkowaNkowa in the province of Limpopo, South Africa.

Although the Grannies and Duffy and her teammates all become closely tied together and invested in each other’s lives by the end of the book, the acknowledgment that, in the beginning, it did not always feel comfortable and easy to navigate is important. Duffy’s contemplation of the “why” behind the work is crucial.

After initially viewing the video about the Soccer Grannies, Duffy feels a longing to reach out to them, especially after she shares their story with her teammates. As a latecomer to sports herself, she finds their story to be inspiring. Through a bit of research, Duffy finds the contact information of the team captain and founding member, Rebecca “Beka” Ntsanwisi a.k.a Mama Beka. Duffy signs off her email to Beka suggesting “perhaps we could be sister teams?” (9) From the start, Duffy is open to connection and engagement.

In addition to heading up Vakhegula Vakhegula, Beka is also an activist, radio host, and provider in her community who is known to constantly be working on different projects to support her less fortunate and often struggling neighbors, despite her cancer diagnosis when she was in her forties. Beka wrote the foreword for the book where she shares openly about her goals and what she hopes will be the impact of telling this story: “This book is important because it will help people around the world understand the challenges the Grannies face every day. I hope Soccer Grannies inspires readers to support my plans to build a home for the elderly of South Africa.” (xvii) The Grannies that make up the team lived through most of the apartheid period in South Africa (1948-early 1990s) and, in addition to racism, have faced sexism their whole lives. Now, as older women, they deal with health ailments and ageism, especially when they are seen playing on the soccer pitch.

The book’s main event is the Soccer Grannies’ journey to the United States, specifically the Boston area, to participate in the United States Adult Soccer Association’s Adult Soccer Fest, which hosts an annual soccer tournament, held in a different location each year. Duffy’s goal back in early 2010, once she conferred with her teammates on Lexpressas and other players in her league, is to invite the Soccer Grannies to join the tournament that year and have a chance to visit the United States and engage with other adult soccer teams. This idea sets off a flurry of emails between Duffy and Beka, where Beka expresses her excitement and delight that the team could play in a tournament in the United States. As they go back and forth making plans for the Soccer Grannies to arrive, there is much to figure out, and the struggles of trying to organize such an event when you have almost no institutional support are made clear. Duffy is able to secure the cost of the plane tickets, totaling around $42,000, from a company that sponsors athletic teams and had learned about the Soccer Grannies’ desire to play in the United States. Duffy and teammates also fundraised locally to get the Grannies’ hotels and visas covered, including contributing plenty of their own money. There is much to negotiate with travel visas and ensuring each of the Grannies has a passport. Many trips from NkowaNkowa to Johannesburg (a five-hour journey) were made to ensure that everyone had the necessary documents. There is so much red tape to get through, it is not until the day before the Grannies are supposed to fly to Boston that all of their paperwork is secured and their passage is guaranteed. This situation speaks to a larger issue: even when money is available and opportunities are presented, it can be very challenging to make this type of connection happen without the help of a larger institutional body that carries more weight.

Once they arrive, there are many sweet moments throughout the Grannies’ trip to the States and beautiful interactions that the Grannies have with their competitors, regardless of their quality of play. Although they lost all of their games, after each one they celebrated with the opposing team, dancing and exchanging gifts. Duffy and teammates learn later that the Grannies normally play much shorter matches, rather than the forty minutes that were standard in the tournament. So, after flying over fifteen hours, the Grannies almost immediately played three matches that were much longer than their usual and in hot, humid Boston summer weather. Duffy often comments on the joy expressed by the Grannies on the field, which speaks to a celebratory spirit that the Grannies express through the game of soccer and also exemplifies the power of sports to create a sense of belonging. Gifts are exchanged, dance moves learned, and lots of food is shared. The Grannies do insist that they need a trophy to bring back with them to show their local leaders what they have accomplished. In the end, no matter the beautiful intentions, or how many friendship and connections are made, winning still matters.

The history of apartheid provides context to understand the struggles and triumphs of the Soccer Grannies, allowing for the reader to understand what the Grannies have been up against in their journey to build their soccer community.

Throughout the book, Duffy interweaves stories from many of the Grannies, told in the third person, including mostly direct quotes from individual Grannies about their lives. They have all experienced racism and the extremes of the apartheid system; they have all experienced financial hardship and desperation; and they have all experienced loss of life in their community from AIDS and other diseases to violent crimes. One Granny in particular, Bull, was the victim of domestic abuse for years, sharing, “‘My husband beat me. Too much. Too much. He hit me every night. I used to have teeth,’ she says, stopping to remove a dental bridge, revealing a gap of four front teeth.” (122) The details of the stories give the reader intimate knowledge of the Grannies’ lives and their experiences prior to finding themselves on the soccer field, looking to improve their health and get outside of their homes where they are often responsible for the caregiving and financial support of their grandchildren. The change of voice, from Duffy’s present narrative about the journey of the players from South Africa to the United States to these intimate stories of the past, contrasts well with the voice of the Grannies as they give us a window into their lives.

Duffy lays out some history of women’s soccer to offer context for how far the game has come. I had not known previously that the first matches of women’s soccer took place in Scotland in 1888. South Africa had its first women’s match in 1962. She also gives a brief overview of South African history, including the fact that soccer arrived via colonizers before indigenous communities made it their own. And that the Natives Land Act, passed in 1913 by the newly formed government of the country of South Africa, designated 90 percent of the country’s land for White ownership, who at the time comprised 20 percent of the population. The legacy of this law is still harming the Black population of South Africa today. (37) The history of apartheid provides context to understand the struggles and triumphs of the Soccer Grannies, allowing for the reader to understand what the Grannies have been up against in their journey to build their soccer community.

The way that the soccer communities are discussed in this book is not building towards a larger goal, but much more focused on the immediate benefits of the game, including well-being and happiness for the players.

Duffy honestly confronts the reality of racism in her dynamic with Vakhegula Vakhegula. She expresses concern for playing the role of or being seen as a “White savior,” especially after Beka reaches out to Duffy for financial help early on, before the team arrives in the States, to help build a home for a local, struggling family. Duffy’s concern about her White community in relation to the all-Black members of the Soccer Grannies is clear. Speaking of her work with her teammates to secure funding for the Soccer Grannies to travel to the United States and providing money for Beka for a personal favor, Duffy says “What were we doing? Why exactly were we getting involved? This had all grown so quickly. What was our motivation? Were we trying to help a family in desperate straits? Were we trying to please Beka or make her feel good about helping? Were we giving money to make ourselves feel good?” (31) This is an important subject to discuss. Although the Grannies and Duffy and her teammates all become closely tied together and invested in each other’s lives by the end of the book, the acknowledgment that, in the beginning, it did not always feel comfortable and easy to navigate is important. Duffy’s contemplation of the “why” behind the work is crucial. By the end of the book, you can see that the support and understanding are mutual, even if it comes in different ways.

After the Grannies had returned to South Africa, Duffy, her daughter Karen, and a few of the teammates that also played huge roles in bringing the Grannies to the tournament, planned a trip to visit them in NkowaNkowa. A year later, they were welcomed into the community there and spent time on the Grannies’ home turf, attending ceremonies with live music and dancing, a feast with the village chief and, of course, playing matches on the soccer pitch. Something that stood out throughout the book was a perspective on sports that is sorely lacking from most of the stories we hear: adults playing sports to have community and to have fun and be healthy. The most widely shared narratives around sports are often about children and the sacrifices that are made for them to dedicate their time to a certain sport, and working towards a larger goal. The way that the soccer communities are discussed in this book is not building towards a larger goal, but much more focused on the immediate benefits of the game, including well-being and happiness for the players. As Lexpressas are getting ready to leave and head back to the States, Duffy reflects, “I had become part of Beka’s community. She’d offered, and I’d embraced the chance to share her dreams of a South Africa that is stronger and safer for its mothers.” (193)

The story is not just about soccer or football or even community and connection. We also see example after example of people willing to take chances on each other. Duffy sends an email after seeing a video online, Beka responds with an openness that allows for Duffy to invite her and the other Grannies to the tournament, and despite communication barriers and a bureaucratic nightmare, both groups, the Lexpressas in Massachusetts and the Grannies in South Africa, work to make the trip happen and are willing to show up for one another.