Thanksgiving or the Ritual of Gratitude

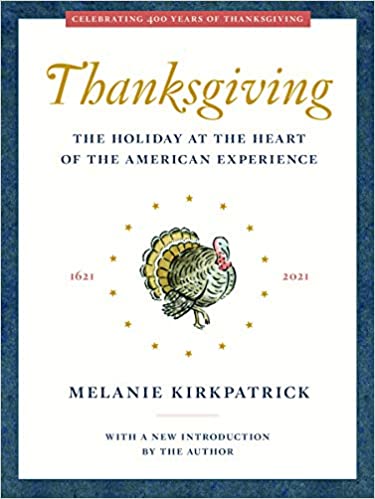

An author’s reissued history of the most American of all our national holidays.

By Gerald Early

November 24, 2021

Thanksgiving: The Holiday at the Heart of the American Experience

1. The Negroes’ Thanksgiving

There are four remarkable things to notice in Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech. First, it is structured like Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. White Americans are Scrooge. Remember, he told the gathering at the March on Washington, that they had come “to cash a check” based on the words of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. But “America had given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’” White Americans had become miserly and dishonest, refusing to honor their debts.

Second, we get King speaking in the tongue of ghosts. We get the Ghost of Race Relations Past at the beginning of the speech in the evoking of Lincoln and slavery. (Giving the speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial reinforces the august moment of the freeing of the enslaved.) Then, we get the Ghost of Race Relations Present with King’s account of the Negroes’ mood in 1963 and their insistence on now. Finally, when he delivers the peroration, the part everyone knows and quotes, we get the Ghost of Race Relations Future, what race relations in the United States can and ought to be.

“I Have a Dream” is a strikingly patriotic speech, the hard-earned patriotism of Negroes and the expression of thanksgiving at the end only intensify how deeply American the speech is. Nothing goes according to plan, and the days following the March on Washington were sometimes glorious, sometimes unspeakably tragic.

Third, King says his dream “is deeply rooted in the American Dream,” reminding his audience that Negroes are not foreign entities but as deeply entrenched in the culture and meaning of our country as the Whites are; the aspirations of Negroes are in the tradition of the aspirations of American democracy itself.

Fourth, King’s last line thanks God for the freedom that will come for Negroes. The speech ends as a prayer of thanksgiving. King expresses gratitude for the success of the Negro revolution and for how it will transform the nation. The gratitude, of course, is not for Whites and their concessions but to God for changing the hearts of the Whites, for giving Negroes their courage, and for endowing the nation with the capacity to redeem itself. Giving thanks, as Melanie Kirkpatrick reminds us, is an American preoccupation, a powerful religious and civic expression of our nation. “I Have a Dream” is a strikingly patriotic speech, the hard-earned patriotism of Negroes and the expression of thanksgiving at the end only intensify how deeply American the speech is. Nothing goes according to plan, and the days following the March on Washington were sometimes glorious, sometimes unspeakably tragic. Negroes became Black people and re-thought what it meant for them to be Americans as they re-thought what giving thanks and expressing gratitude meant.

2. “Pursuing the Happiness”

In her preface to the 2021 paperback edition of Thanksgiving, marking the 400th anniversary of the American Thanksgiving, Melanie Kirkpatrick expresses her concern for the continued celebration of the venerable holiday. “Given recent attacks on Washington, Lincoln, and other heroes of American history, it was only a matter of time before cancel culture came for Thanksgiving.” (x) Her use of the word “heroes” clearly places her on a particular side in this installment of the culture wars, but her worry is legitimate. Thanksgiving could fall, condemned as a symbol, a relic of White supremacy, simultaneously celebrating and masking genocide, colonialism, and racism, just as Columbus Day has died an ignoble (and for many a deserved) death across a good swath of the United States. The fact that Kirkpatrick does not touch upon this at all in the introduction to the 2016 edition of her book shows just how decisive (Kirkpatrick would probably say destructive) a force cancel culture has become in a mere five years.

What Kirkpatrick particularly objects to is the left’s assertion that the origin of the holiday is in the thanksgiving that the English settlers held after the mass killing of the Pequot men, women, and children in what is known as the Mystic Massacre that ended the Pequot War of 1637, sixteen years after William Bradford and his band of Pilgrims celebrated what is now considered the first Thanksgiving as a peaceful gathering with Native people. She calls the left’s association of this tragedy with our national Thanksgiving celebration “a slur.” (x) (The Pequod was the name of the ill-fated ship captained by Ahab in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick. The Essex was the name of the actual ship upon which Melville based his story.)

Thanksgiving could fall, condemned as a symbol, a relic of White supremacy, simultaneously celebrating and masking genocide, colonialism, and racism, just as Columbus Day has died an ignoble (and for many a deserved) death across a good swath of the United States.

Kirkpatrick argues that “[the] practice of giving thanks for military victories—as Washington, John Quincy Adams, and every wartime president since Lincoln and Jefferson Davis have done in Thanksgiving proclamations—is but one of many sources of the holiday.” She is certainly correct that most people have not heard of the Mystic Massacre—although it is starting to make its rounds in K-12—and that our Thanksgiving is based on the story of the fifty-two Plymouth Pilgrims having a Thanksgiving feast with ninety Wampanoag warriors in the late summer or early fall of 1621; the Pilgrims thanking God for their survival after the first disastrous winter of the previous year shortly after they first arrived on these shores. Half their number died. Without the Indians, particularly an English-speaking member who had lived (and been enslaved) in Europe, Squanto, a Patuxet, and Massasoit, the chieftain of the Wampanoag Confederation, none of the settlers would have made it. Squanto, a highly assimilated Indian from his time in Europe, died a year later, bequeathing his belongings to the English.

The Wampanoag and the English settlers signed a peace agreement that lasted nearly fifty years. If anything, what Kirkpatrick suggests is that this moment, which has become the icon of our Thanksgiving celebration, is about the hope and promise of the Natives and the English living together in peace and harmony. That things fell apart as they did is all the more heartbreaking in light of this feast of 1621 and what we celebrate, in part, is the endurance of that hope and promise. That many Native Americans today feel ambivalent about Thanksgiving is hardly surprising, just as many Black Americans are ambivalent about the Fourth of July. Kirkpatrick is sympathetic to this. She is less so to White leftists and liberals tearing down the holiday on the basis of what she feels are, at best, half-truths.

She might have added that to understand the English settlers, one has to understand their religious view of the world and of their sojourn to the so-called New World. This is difficult for a secular-minded intelligentsia who are likely to think that religious people, or religiously inclined Europeans, are insincere or delusional. Like the Israelites crossing the Jordan, these Puritan Separatists and their descendants saw themselves embarked upon “an errand in the wilderness” in their crossing of the Atlantic. They would have seen their massacre of the Pequot, their “victory,” in which they were joined by the Narragansett and the Mohegans, as an expression of God’s favor, of God’s providence, not as a proof of implacable, pathological racism, although they were surely racist. They would have pointed to Scripture showing the passages where God favored Joshua and the Jews in their conquest of the native peoples when the Israelites crossed the Jordan. As the English Dissenters would have seen it, if God had favored the heathen Indians—which they would have found difficult to imagine—the Indians would have massacred them and won. And did not the Israelites celebrate their military victories by giving thanks to God? (The Negro spiritual, “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho” is about the Israelites conquering the people of Jericho when they crossed the Jordan, and, as the song notes, they thanked God for their victory.) They would not have comprehended why that was bad, why anyone would think so.

That many Native Americans today feel ambivalent about Thanksgiving is hardly surprising, just as many Black Americans are ambivalent about the Fourth of July. Kirkpatrick is sympathetic to this. She is less so to White leftists and liberals tearing down the holiday on the basis of what she feels are, at best, half-truths.

In any event, Thanksgiving may one day be capsized and replaced by, as one professor desires, “a national Day of Atonement and collective fasting,” (137) a sort of American Yom Kippur but, as St. Augustine once said in another context, “not yet.”

Kirkpatrick’s enjoyable, easy book reminds the reader of how popular Thanksgiving is and how, as much as if not more than the Fourth of July, it defines us as Americans. It is probably the most popular of all American holidays among immigrants because they identify with the Pilgrim story. (xv-xxii) It is associated with food, family, and football, in other words, abundance, leisure, recreation, love, togetherness. And for this, the blessings made manifest on this day more so than on others, we show our gratitude to our nation and to God. Thanksgiving is so lushly about, as one of the high school immigrant students told Kirkpatrick, “pursuing the happiness,” and being grateful that one can pursue it.

(In regard to football, by the way, St. Louis’s Webster Groves and Kirkwood high schools are mentioned for having the oldest Thanksgiving Day football game west of the Mississippi. It began in 1907. [103] Woe be to the poor, winless Webster Groves Statesmen this year as they go against a decidedly superior Kirkwood team on Turkey Day 2021.)

Thanksgiving provides a history of the holiday: how Bradford’s Pilgrims and the Indians became the symbol for it despite other thanksgiving celebrations between Europeans and Indians that preceded it; why George Washington signed the first presidential proclamation for the celebration of a national Thanksgiving and how every president from Lincoln on has issued such a proclamation; how the holiday is an example of our federalism as the president issues a proclamation but states actually approve the celebration; how the holiday became fixed on the fourth Thursday of November, despite Franklin Roosevelt’s efforts to change it; how Sarah J. Hale, the influential editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, pushed for years for a national Thanksgiving; how football and turkey became indelibly connected to the holiday.

Above all of this is Kirkpatrick’s true theme: showing gratitude. My sense is that she thinks many Americans do not feel sufficiently grateful that they are Americans. As a sense of entitlement and a culture of complaint suffuses the land, gratitude seems not only a lost emotion or form of psychological and cultural etiquette but a disregarded, even despised one. No one should have to express gratitude for what you are owed and by right should have. Gratitude is the expression of the political Uncle Tom, the empty-headed patriot, the insincere opportunist, the hosanna shouting religious fool. Kirkpatrick’s fear is that the left’s attempt to banish gratitude unravels our country by denying it any dimension of humanity except its quest for power. This is why I think this book, as an unabashed, loving defense of Thanksgiving as tradition would have it, is a not-so-subtle shot in the culture wars.

Aside from being informative about the holiday, its ideological bent should make Thanksgiving a curious read for many people.