There is a tendency for many people to think of television of the 1950s and 1960s as, to use a clichéd phrase, a vast wasteland strewn with unsubtle, hard-selling, jingle-driven commercials; white bread, conformist, suburbia wonderland family sitcoms like The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, The Donna Reed Show, Make Room for Daddy, Leave It to Beaver, and Father Knows Best; bland, pseudo-hip detective shows like 77 Sunset Strip and Peter Gunn; overworked, formulaic westerns like Laramie, Wagon Train, Cheyenne, and Bonanza; standardized white bread variety shows ranging from Perry Como to Dean Martin to Andy Williams to Dinah Shore all signifying the last gasp of the Great American Songbook; even more tired and formulaic knock-offs of James Bond-like The Man from UNCLE, The Wild Wild West (also a western), The Girl from UNCLE, and Amos Burke, Secret Agent; execrable comedies like My Mother The Car, The Beverly Hillbillies, and The Munsters, a knockoff of the much better Addams Family. Television has always been bad, in many ways, which is what makes it so enjoyable, such a guilty pleasure. There is very little artistically at stake in watching it, which makes it relaxing in its predictability, boringly accessible, and engrossing as a form of passivity and engagement. Television is not really a form of self-forgetting but rather a particularly conflicted form of self-awareness: television was, in the days when it was a piece of furniture, both the dark mahogany stranger in the house and the loyal companion, both threatening and familiar, something that seemed to control and something that seemed to transport. The mistake that people today make is assuming that television audiences of fifty years ago were more naïve. They were simply more concentrated and television as a gadget was still confoundingly new. Generations had not grown up on it yet. The baby boomers were the first.

There was, of course, some gold among the dreck: Combat was one of the best war dramas ever telecasted; the James Garner episodes of the highly original western comedy, Maverick, the first about a gambler (Yancy Derringer was a knock-off), are still good over 50 years later; Gunsmoke, one of television’s longest running shows, was more realistic and gritty than many television westerns of the time; Dr. Kildare made hospitals seem more profoundly melodramatic than they really were; Checkmate had one of the most memorable themes of ‘60s television, written by John Williams; Then Came Bronson was an earnest dramatic knockoff of the film Easy Rider and Route 66 was an earnest dramatic knockoff of Kerouac’s On the Road. (Serious television dramas of the 1960s tended to be earnest in a way that would strike most young viewers today as talky, tedious, corny, and flat-footedly liberal in their sentiments.) But here are a few shows that were particularly innovative, even revolutionary, for their time.

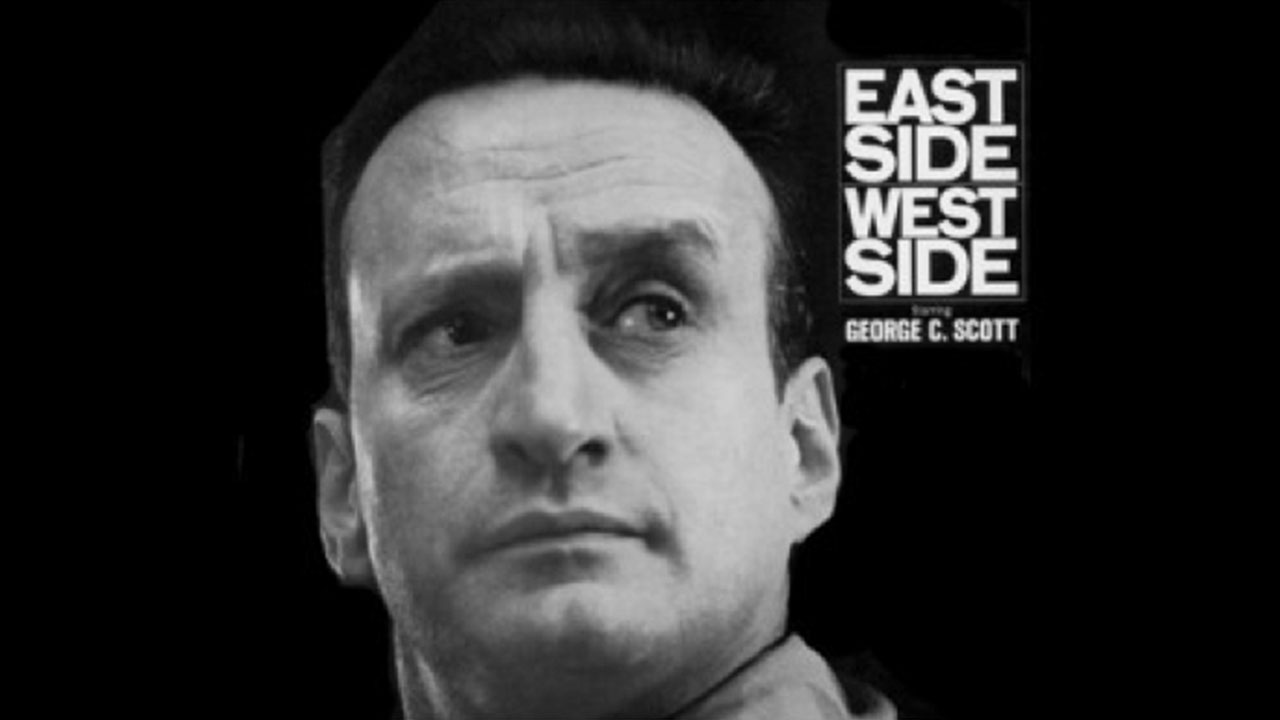

- East Side, West Side (1963–1964)

Accomplished film actor George C. Scott played feisty, leftist social worker Neil Brock in a drama about the trials and tribulations of a social work agency in New York City. The show featured black actress Cicely Tyson in the supporting role of Jane Foster which attracted many black viewers as Tyson was the first black actor with a recurring role in a television drama. She wore what was called at the time a natural, later to be called an Afro, which made her decidedly an object of attention among many black women who found the hairstyle shockingly different and even unflattering at the time. The hairstyle clearly indicated a kind of political self-awareness for the character that was startling. Indeed, the show featured more African Americans in background shots (there was lots of location shooting), more disarmingly frank discussions about race and about politics, more gifted black actors in guest starring roles like James Earl Jones and Diana Sands, than one would find in any television show of the period, in fact in all television shows of the period put together, which probably explains why it was very difficult for the show to find sponsors and why it only lasted for one year on CBS.

The episodes were realistic, rarely resolved happily with Scott’s character saving the day. (It is in fact interesting how often Scott’s character, despite his efforts, was often impotent in helping anyone. This probably made the show unsatisfying to many viewers who chose not to watch it after one or two episodes.) It is surprising that all schools of social work do not have a portrait of the cast enshrined in some place of honor as the show was such a tribute to the social work profession. I think it was the most brilliant and original dramatic series of the 1960s.

- The Defenders (1961-1965)

One of the more realistic and socially concerned of 1960s lawyer programs, CBS’s The Defenders starred E. G. Marshall and Robert Reed (who went on to play the father in The Brady Bunch) as a father-and-son legal team—Lawrence and Kenneth Preston—with an endless number of clients that brought to viewing audiences real world situations. For many, it was considered the most socially conscious series ever on television. The Prestons defended mercy killing doctors, abortionists (an episode which nearly had no sponsors), and prison rioting for better conditions. It was far more engaging than the formulaic Perry Mason, CBS’s, indeed television’s, most popular lawyer program in the 1960s. There were few witness confessions in The Defenders; such confessions were the sine qua non of Perry Mason. Of course, suffused with urban naturalism, there were episodes that dealt with race; like East Side, West Side, it was shot in New York City and had a greater black presence in ambience and crowd scenes than one usually found on television at the time. Unlike East Side, West Side, The Defenders was popular. Many black people I knew loved the show. (They also liked Perry Mason for nearly the same reason: both shows revealed how the criminal justice system can screw you up.) The Defenders was fiercely, earnestly liberal, so, while it criticized “society,” it ultimately did not discourage trust or faith in American institutions.

- The Twilight Zone (1959-1964)

The most well-regarded anthology series in the history of television, The Twilight Zone’s quirky, creepy, highly moralistic tales were, for a kid like me, the next best thing to reading EC comics. And no television auteur achieved the fame of Rod Serling, a fame where his name and presence and this show were indelibly connected. Not even Gene Roddenbery with Star Trek was as mythically tied to a program the way Serling was with The Twilight Zone. Even casual viewers know about the most famous episodes in the series: Burgess Meredith, the last man on earth, breaking his glasses just when he is about to sit down and read all the books he finally has time to read; Agnes Morehead fighting off an alien invasion with a broom; William Shatner as an increasingly agitated passenger seeing a monster on the wing of a plane; Gig Young as an overworked executive who is able to go back to childhood past; Jack Warden as a convicted murderer on a distant planet who falls in love with his robot companion. Even the most dated and lackluster episodes of The Twilight Zone are engaging as failures.

- Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-1965)

The second-best anthology series of its time, it creeped me out even more than The Twilight Zone and even more than EC comics. Even the theme music, a snippet of Gounod’s “Funeral March of a Marionette”, scared the bejesus out of me. Yet there were no monsters such as those that appeared regularly in The Outer Limits the premiere science-fiction television show of the 1960s, nor was there the flat-out weirdness of The Twilight Zone. Hitchcock introduced the episodes and occasionally directed. The actors, writers, and directors were generally among the best in television at the time. As a half-hour program, it was simply superb. When it became an hour in 1962 and dubbed The Alfred Hitchcock Hour the show was still good but not as peerless as it was before. “Where the Woodbine Twineth” remains for me the most memorable and richly complex of all the hour-long episodes.

- Julia (1968-1971)

Diahann Carroll played a widowed nurse with a young son in this pathbreaking comedy series, the first to feature a glamorous black actress as a wholesome television lead. The show was hated, utterly despised by many young black activists and militant-types I hung around with at the time. (I was in high school.) They called Diahann Carroll everything but a child of God, as the old black saying goes. At the time, many blacks wanted a television show about the ghetto, poverty, and the problems of black life, not a television heroine who lived an unreal, integrated, sanitized life wearing designer clothes and living in an apartment that she could hardly afford as a nurse. Many also complained about the lack of a black man in the show, although Diahann Carroll’s character did date. In many respects, this show was the forerunner of later black family comedies like Norman Lear’s The Jeffersons (middle-class black family with a father) and Good Times (black family in the project with a father for the first three seasons of its run). The “Julia” impulse of integration with respect and racial pride without militancy culminated with a show like The Cosby Show where a whole black family has truly made it. “Julia” was in the spirit of the Sidney Poitier-integrationist driven films of the period. Shows like this were meant to show whites (and blacks) that blacks were just like everyone else and worthy of entering the house of western civilization. But many blacks, especially older ones, like the show because it showed a dignified single black woman with a son living a glamorous middle class, living in fact as a white character in a similar kind of sitcom would be living. This little puff of a show has a certain sweetness that touched me.