One of the many things in short supply in our recent politics is nuance. Because both parties have become ever more ideological, there is a disturbing tendency to see things in black or white and ignore the fact that in some ways gray is a more appealing color. Nowhere is this trend more apparent than when discussing the presidency of Donald Trump.

Many of Trump’s supporters think he can do no wrong. By contrast, his adversaries often think that whatever he is for must be bad for the country and that he was close to being a totalitarian leader. The reality is that while Trump would have loved to have been a strongman like Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez or Hungary’s Viktor Orbán he lacked the skills to do so. Also, the American system of checks and balances worked and restrained Trump when necessary.

Barr spends a great deal of time spelling out the former president’s shortcomings, including his bullying style, impetuousness, and unwillingness to take advice that contradicts his instincts. Barr stops just short of calling his former boss a jerk and one comes away thinking that working for Trump is about as pleasurable as root canal surgery.

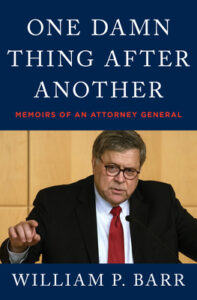

Trump’s second attorney general, William P. Barr, makes no attempt to be objective about the presidency. However, his just-published memoir, One Damn Thing After Another: Memoirs of an Attorney General, is an insightful and engaging account of a tumultuous period in American history.

Those expecting a strong defense of Trump the person will be disappointed or pleasantly surprised, depending on their worldview. Barr spends a great deal of time spelling out the former president’s shortcomings, including his bullying style, impetuousness, and unwillingness to take advice that contradicts his instincts. Barr stops just short of calling his former boss a jerk and one comes away thinking that working for Trump is about as pleasurable as root canal surgery.

Barr argues, though, that Trump’s erratic behavior was reinforced when he was attacked, without merit.

“He was under a constant barrage of heinously unfair attacks from his Democratic opponents and their allies in the media. But the Trumpist imperative of automatically responding to any provocation with massive retaliation added to the bedlam got him distracted, and gave his adversaries an easy way to portray him as a bully. They had his number, it was easy to provoke him into overreaction,’’ he writes. (513)

Barr is partially correct.

Much of the media cut Trump far less slack than it did other presidents. Many mainstream publications crossed the line from reporting aimed at holding officials accountable to dismissing any of Trump’s policies as inherently awful.

However, members of the media who made legitimate points about the shortcomings of Trump’s policies were doing responsible work. The reportage about the problems of Trump’s immigration policies and his response to the protests following police shootings are examples of that. Yet Trump could not fathom that any criticism of him might possibly have a basis in fact.

The best parts of the book are when Barr recounts private meetings with Trump, especially when he pushes back on some of the president’s tendencies to meddle in the work and investigations of the Department of Justice. To be sure, some of the anecdotes have an “if-he-had-only-listened-to-me-more-things-would-have-been-less-messy” tone. But Barr makes the reader a proverbial fly on the wall.

Unfortunately for the reader, Barr not surprisingly withholds some potentially interesting information.

Barr was not always a Trump admirer. He supported a range of other candidates—and was something of a never-Trumper until Trump won the nomination in 2016. He loathed Hillary Clinton and her policies and was still angry that her husband defeated President George H.W. Bush, for whom Barr also served as his second attorney general.

The best parts of the book are when Barr recounts private meetings with Trump, especially when he pushes back on some of the president’s tendencies to meddle in the work and investigations of the Department of Justice. To be sure, some of the anecdotes have an “if-he-had-only-listened-to-me-more-things-would-have-been-less-messy” tone.

Like many on the right, Barr saw Trump as the lesser of two evils. Trump sweetened his appeal by releasing a list of very conservative judges from which he planned to select Supreme Court justices. (1) That was music to the ears of Barr, who, one learns from this book, is an accomplished bagpipe player. (2)

Trump picked Barr halfway through his term after firing Attorney General Jeff Sessions, in part, because Sessions recused himself from any oversight into the DOJ’s investigation of Russia’s involvement in the 2016 campaign.

Barr was justifiably skeptical that there was collusion between Russia and Trump’s campaign, though he admits that the Russians took major steps to help Trump’s candidacy. When he started the job in early 2019 Barr let the investigation by special counsel Robert Mueller continue.

The Mueller report concluded that “the evidence does not establish that the president was involved in an underlying crime related to Russian election interference.’’ As for obstruction of justice, the report stated that the investigation “does not conclude that the president committed a crime, it also does not exonerate him.’’ (3)

Barr refutes accusations that his initial summary of the report misrepresented some of its conclusions, by not explaining their broader context. He also criticized Mueller’s report for its “fuzzy logic.’’ He concluded that “Mueller and his team didn’t have what they needed to prove obstruction but couldn’t bring themselves to say so.’’(248)

Barr explains his actions with lawyerly thoroughness yet also criticizes Trump for behaving in a manner that was “exactly the opposite of how a lawyer would counsel someone to handle an investigation.’’ (248)

Barr concludes that Trump’s behavior that led to his first impeachment, withholding aid to Ukraine unless the government gave him damaging information on Joseph Biden, was a “self-inflicted wound.’’ (300)

He adds that Trump’s actions were foolish, not criminal, and makes the broader point that: “Not all censurable conduct is criminal. The current tendency to conflate the foolish with the legally culpable causes more harm than good.’’(310)

It is advice that Democrats should have taken in this instance and that Republicans should have heeded during the Clinton impeachment.

As for the 2020 election, Barr is justifiably proud of his own efforts to try to persuade the former president that there was not enough fraud to have affected the outcome. Barr had his department investigate allegations and repeatedly told Trump what Trump did not want to hear.

However, his description of Trump as “struggling to come to terms’’ with the result is too charitable. Trump wanted to overturn the results and his efforts no doubt helped fuel some of his more extreme supporters to storm the Capitol on January 6, 2021, to try to stop Congress’s vote counting. Barr said Trump’s actions that day were a “betrayal of his office and supporters.’’ (558)

However, Barr does not think that Trump’s actions constituted an incitement to violence. Unfortunately, he does not explain the reasoning behind his opinion.

While Barr’s account of the events of the Bush and Trump presidencies is worthwhile, one cannot say the same about his discussion of the culture wars. He is quite conservative and offers a strong defense of his worldview and a withering critique of his adversaries.

He describes his own philosophy as traditionally liberal adhering to the principles of John Locke and others and maintains that it “gives priority to the preservation of personal liberty.’’ By contrast, he sees progressives as supporting “a form of soft totalitarianism that aims explicitly at tearing down the liberal tradition and submerging the individual in a collectivist agenda.’’ (169)

While Barr’s account of the events of the Bush and Trump presidencies is worthwhile, one cannot say the same about his discussion of the culture wars.

Barr is not self-aware in this part of the book. In recent years, conservatives have been just as willing to impinge on individual rights as progressives, albeit to further their goal of implementing their moral agenda. Limits on abortion, same-sex marriage, and access to contraception have been priorities of the right.

Fortunately, Barr’s culture war rhetoric is a small part of his otherwise worthwhile book.

Trump supporters may consider him something of a modern-day Judas Iscariot and Trump critics will deem him to be a shameless apologist. But those who take the time to read One Damn Thing After Another: Memoirs of an Attorney General will learn a great deal and have the chance to draw their own conclusions.