The St. Louis area is incredibly rich in late 19th and early 20th century architecture, parks, and planned suburban enclaves, yet to date most of the scholarly literature on the built environment of what was once the fourth largest city in the United States has been very limited. This book is a welcome effort to expand our knowledge of the elaborate, early 20th century mansions designed at the western edge of the city and in its inner suburbs by Raymond Edward Maritz (1893‐1973) and his associates.

The dozens of Maritz houses described here by Maritz’s firms, designed between 1915 and 1941, were built for leading figures in St. Louis business and professional life in new subdivisions at what was then the outer edge of St. Louis urban development. The industrial and financial activity that had made St. Louis so important nationally and internationally was largely centered east of Grand Boulevard before the 1940s, and these new areas near and just beyond the city limits of 1876—the year when the county and the city became two separate governing entities—continued earlier St. Louis patterns of urban westward growth along streetcar lines.

Raymond Maritz first became interested in architecture as an 11-year-old, after his father, a jewelry manufacturer whose firm later became Maritz, Inc., took him to meet with the architects and engineers who were designing the Beaux‐Arts style French Pavilion at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Raymond went on to study architecture at the nascent program in Architecture at Washington University, then part of the School of Engineering, before continuing his studies at the Ecole des Beaux‐Arts in Paris, at the time the leading professional school of architecture in the world. He returned to France in 1915 to volunteer with American Field Service (AFS) to transport wounded French soldiers. On his return to St. Louis, Maritz established the first of his offices downtown, in the Chemical Building, then moved to Webster Grove where he resided.

As the book documents, Maritz’s work as an architect began with the design of two houses in the recently laid out Clayton subdivisions just west of Big Bend Boulevard called Forest Ridge and Southmoor Drive. These mansion streets, like many in other areas of Clayton and University City near the city limits, were planned by Henry Wright (1878‐1936), later well known as the co‐designer with Clarence Stein of the model working-class town of Radburn, N.J. (1928). After his marriage to another Washington University graduate, Frances Duffett, Raymond Maritz established another firm, Maritz & Young, in 1920, with his former office manager, William Ridgely Young, also an architecture graduate of Washington University. Both men became central figures in the St. Louis chapter of the American Institute of Architects from 1924‐35.

As Amsler and Schott explain, the Maritz & Young mansions “dominated stylish boulevards and drives with names such as Lindell, Forsyth, Carrswold, and West Brentmoor.” The firm had mastered the art of designing imposing, finely crafted, yet comfortable and commodious large houses suited to the local climatic extremes, well before air conditioning had come into use. In 1925, they also completed the former United Hebrew Temple (now the Missouri Historical Society Library) on South Skinker Blvd., in consultation with Gabriel Ferrand, the Beaux‐Arts trained director of the Washington University architecture department. They also designed the Clayton City Hall at 10 S. Bemiston in 1930, as well as some new country club clubhouses, along with a handful of larger commissions. A two-volume monograph of their work was published in 1929‐30.

Although the firm continued to exist during and after the Depression, becoming Maritz, Young, & Dusard from 1934‐40 and Raymond E. Maritz & Sons in 1948, this book focuses largely on their work in the 1920s and 1930s, primarily in Clayton, Ladue, Huntleigh, and along Lindell Boulevard. More than 50 houses are described in detail and illustrated with period black-and-white photos and architectural drawings, providing considerable information about both the architecture and the clients’ lives and business and professional affiliations. A good example is the authors’ two-page discussion of the Vincent Price, Sr. house on Forsyth Boulevard, across from the Washington University Danforth campus, one of the many houses the firm designed along this street in the 1920s. The client was the Yale‐educated heir to a baking powder fortune, who had moved to St. Louis to establish the National Candy Company, which had tremendous sales during the 1904 Fair. His wife founded the Community School then on DeMun Avenue. In 1923, Price turned to Maritz & Young to design the house in a Georgian Revival style, which his daughter recalled he saw as American, while his wife wanted an Asian theme for the interiors. Somehow the architects were able to accommodate these demands and produce yet another effective design, which was the childhood home of the film actor Vincent Price, Jr. Nearby is the firm’s Spanish Colonial style William Levin House (1925), for the president of a family metals business, featured in the 1930 book, Modern Homes. Its dramatic double-height living room and arched breakfast room is illustrated here with period photographs by Leroy Robbins, who had studied architecture at Washington University and then became the official photographer for the St. Louis Art Museum. Not far west are several Maritz & Young houses on Carrswold Drive, laid out around a central green space by the Chicago landscape architect Jens Jensen in 1922, all illustrated and discussed here.

These houses were of course the product of a different time than the present, when social norms were such that only men were expected to work, and women (if they could) were expected to stay at home. African‐Americans were rarely visible to the elite except as servants, despite a growing population in the St. Louis area after World War I. Streetcar networks were extensive and widely used, and most major retailing and professional services were only available in the then highly racially segregated central parts of the city. Although this book does mention which of these Maritz & Young houses are now institutionally owned, some of the differences between the time when these houses were constructed and the present could be more emphasized in this book. More detail could also be included on the ways that the houses employed large numbers of different kinds of specialized workers to construct, maintain, and service them. Certainly the level of hand craftsmanship evident in many of these houses would be difficult, if not impossible, to obtain today.

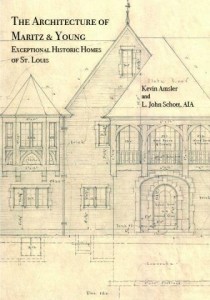

The Architecture of Maritz & Young is a valuable reference book that documents many of these skillfully designed houses, which set a high standard for a relaxed yet formal residential architecture of an especially lavish kind. Echoes of this design approach, whose roots extend back to English country houses and French chateaux, still inform much new North American suburban and institutional construction today. This book adds considerable new knowledge to this key period of the architectural history of St. Louis, where these design approaches were joined to new technologies in what proved to be a very popular synthesis whose later outcomes can now be found in many places.