I spent the 1971-72 academic year as a precocious fifth-grader in Mrs. Mummertz’s class at Whittier Elementary School. A competitive, rather self-regarding eleven-year-old, I sought opportunities to distinguish myself. Class art projects provided one option; the annual spelling bee offered another. And that year, during the run-up to the latter I struggled to contain myself. Anyone familiar with recent history would have known my fortunes were ascendant.

The tournament took place in a school-wide assembly, and included fourth, fifth, and sixth-grade contestants; the winner and runner up advanced to the city-wide competition. The previous year I had nearly finished in the money, coming in third, defeating many older children in the process. I was very proud of this accomplishment, and had nursed hopes—nay, my expectations—ever since. Last year’s dark horse would be this year’s favorite. My confidence was boundless.

When the day came and my turn rolled around, I marched up to the speller’s box. Mr. Haas, the principal, read my laughably easy first-round prompt, “words.”

“Words,” I announced. Then: “W-R-D-S,” I declared, sans vowel. “Words,” I concluded, and determinedly walked back to my seat. Before I got there, Mr. Haas stopped me with his voice. “I’m sorry,” he said ruefully, “That’s not correct.”

Hot-cheeked, aghast, I suffered briefly. Mrs. Mummertz was philosophical. She assured me that one day I would tell that story in amusement. Now I have.

In many of The Peanuts Papers autobiographical narratives, Charles Schulz’s characters are reported to have helped soothe, or at least contextualize, the cruelties of childhood. I do not recall turning to Charlie Brown to salve my spelling-bee wounds, but critically, I was (and remain) less decent than Schulz’s lead character.

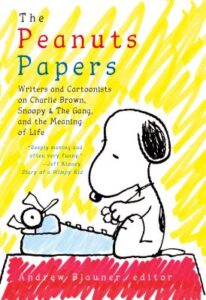

Tales like this one dot the essays in Andrew Blauner’s edited volume The Peanuts Papers, issued for the 70th anniversary of Charles Schulz’s 1950 comic strip debut. (Jonathan Franzen tells one very much like it, in fact, with much higher stakes: about a homonym bee that ends in a tie. Soon we learn that Franzen’s rival was killed in the street by an automobile weeks later.) In many of The Peanuts Papers autobiographical narratives, Charles Schulz’s characters are reported to have helped soothe, or at least contextualize, the cruelties of childhood. I do not recall turning to Charlie Brown to salve my spelling-bee wounds, but critically, I was (and remain) less decent than Schulz’s lead character. I had pretensions; Charlie Brown never did. As many of these writers observe, the boy suffers without surrendering hope, even as he knows a brutal truth: more suffering, and only more suffering, awaits him. Lucy Van Pelt will always pull the football away. His baseball team will never win a game. The Little Red-Haired Girl will never notice him.

Schulz, known universally to friends as “Sparky,” drew Peanuts for fifty years, following a starter strip called L’il Folks that ran in the St. Paul Pioneer Press from 1947 to 1950. Charlie Brown first appeared in print in 1948, a pluckier version of the Beckettian everyman he later became. When Schulz pitched L’il Folks to United Feature Syndicate, they bit, but forced a different title on the young cartoonist as part of the deal. His rendering of the Brown and Van Pelt kids would run beneath the banner of Peanuts. Sparky hated it, and the resentment never faded. “I hold a grudge,” he admitted.

Which hardly surprises, since the strip catalogues indignity after indignity, a fatalistic pageant of unrequited love leavened by sardonic humor, redeemed by humility. The latter saves the enterprise, like the scraggly Christmas tree in A Charlie Brown Christmas. That is especially the case during the 1950s and 60s when Charlie Brown lived at the center of the Peanuts universe. Certain aficionados of the strip see this as the essential Peanuts. Others embrace the later decades, increasingly focused on Snoopy. As the Brown family dog pursues his interests, from flying his Sopwith Camel in battle against the Red Baron to writing fiction—“It was a dark and stormy night,” Snoopy types, again and again—the tone of the strip grows lighter, more imaginative, paradoxically descending into sentimentality. I prefer the bleak intelligence of the earlier strip to the “happiness is a warm puppy” years.

… since the strip catalogues indignity after indignity, a fatalistic pageant of unrequited love leavened by sardonic humor, redeemed by humility.

The Peanuts Papers represents both perspectives. Blauner’s volume offers pieces by 33 authors, divided into five sections: “The Big Picture,” “Characters,” and so on. Amid fragments of childhood autobiography, the essayists provide associative insights, subtle readings, and useful facts.

The cartoonist Ivan Brunetti delivers the best pocket criticism of Peanuts in his essay, “Yesterday Will Get Better.” Among other observations, including Schulz’s injection of melancholia into the “funnies,” Brunetti notes that “Peanuts has no discernible scale, because it exists simultaneously in small increments and a fifty-year totality, an epic poem made up entirely of haikus.” George Saunders makes generous note of the formal and thematic problems that Sparky managed: “If art is seen as a constant battle between freedom and restraint, then Peanuts was great not because it was joyfully unconstrained, but because it managed to be so joyful under constraint.”

A reader will be struck by the web of cultural references used to apprehend Peanuts by analogy or influence. The people, both fictional and real, enlisted in the effort to interpret Schulz include Marlon Brando (by Brunetti), Holden Caulfield and Thomas Merton (Adam Gopnik), Pete Best (Bruce Handy), Vladimir and Estragon (Saunders), Brecht and the Epic Theater (Nicole Rudnick), Dorian Gray (Joe Queenan), the psychotherapist Harry Stack Sullivan (Peter Kramer) Percy Crosby and his comic strip Skippy (David Hadju), George Herriman’s Krazy Kat (Umberto Eco), Fred Rogers (Chris Ware), and Virginia Woolf (Ann Patchett).

George Saunders makes generous note of the formal and thematic problems that Sparky managed: “If art is seen as a constant battle between freedom and restraint, then Peanuts was great not because it was joyfully unconstrained, but because it managed to be so joyful under constraint.”

I could go on. That’s only the first third of the book. The range accounts for the richness of the project, as well as its potential to exhaust a reader.

To write about comics is to contemplate designed form, symbolic drawing, writing, staging, and lettering or typography. The form is a hybrid package of graphic manifestation. Sometimes in comics criticism, the visual finishes a distant second to the literary. In the case of Peanuts, a strong argument can be made for the primacy of text; you could read classic Schulz as prose or poetry without any drawing at all and still track his argument. Even so, the approach would yield a deeply incomplete reading. Brunetti observes correctly that “cartooning exists in a kind of liminal space somewhere between writing and drawing.” This dense composite, especially in Schulz, delivers a totally realized sensibility, which amounts to a worldview.

Of drawing: yes, but what kind of drawing? In a world dominated by incessantly filmed superheroes, harvested from the “cinematic” points of view and elaborate panels that gave rise to them (see Jack Kirby’s work for Marvel; before that Milt Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon, Alex Raymond’s Rip Kirby and Flash Gordon, back to Hergé’s Tintin), it can be hard to remember the austere power of minimal form deployed in the service of poetic writing. Schulz’s Peanuts. Crockett Johnson’s Barnaby.

Chip Kidd’s cover design for The Peanuts Papers includes a magnified drawing of Snoopy at his typewriter, reproduced with fidelity to the ink itself—as opposed to the high-contrast photostat reproductions that flattened pooling washes and subtle grays to declarative, implacable blacks. We see the faint tremor in Schulz’s line, brought on by quadruple bypass surgery in 1981; the variable weight of his contours; the economy of his curves. These last are surprisingly elegant if you regard them in abstract terms, like the beautiful line drawn by Apelles on Protogenes’s panel, an ancient story in Pliny approvingly cited by Apollinaire to apprehend modern painting. The line is the line, a self-referential carpentry. Viewed thus, “Snoopy” can be gorgeous. But because this book does not include the strips as illustrations as they are described or referred to by the authors, visual evidence is, well, not in evidence. Words do all the work.

In the case of Peanuts, a strong argument can be made for the primacy of text; you could read classic Schulz as prose or poetry without any drawing at all and still track his argument.

Certain of the essays in this book are several-page toss-offs. Others are quite substantial pieces of writing that will hold up on their own. Among the latter is Gerald Early’s essay on West Coast Jazz and the Vince Guaraldi compositions inspired by Peanuts (some of which predated the animated Christmas special they appeared in, which was news to me). The animation projects form the strongest connection to Shultz’s creation for several of the book’s essayists.

Early scarcely mentions the strip, but effectively ties the music to the lived world of the characters:

“[In the comic strip] Childhood was not something apart from real life, as many adults like to think of it, but rather it was real life on another scale, a scale that made up in depth of feeling what it lacked in breadth of experience. Guaraldi’s cool themes for the Peanuts specials made childhood’s innocence not Wordsworth-like, as grandeur fallen, but cool, as in learning how go on when you blow it, persevering when the gig goes sideways.”

These sentences go to the heart of Peanuts, as revealed by A Charlie Brown Christmas. Several of Guaraldi’s compositions, and especially the vocal version of “Christmastime is Here,” capture the essential warmth and depth of both composer and cartoonist. The imperfect child’s choir is stocked with Minnesotan Browns and Van Pelts, not Viennese boy sopranos. Despite the inevitable disappointments and unreturned affections–the “good griefs” of life–we can all gamely swing along as the snow falls. For this reason, Guaraldi’s Peanuts tracks are beloved more than admired. As was Peanuts itself among general readers during its run. And taken as a whole, this book makes a serious run at explaining why.

As I made my way through the book, I resisted the urge to cherry-pick essays by my favored cartoonists and writers, plowing straight through, which is probably the wrong way to read this book. The Peanuts Papers should be understood as bathroom reading: Its units are modular. The essays can be read in any order.

Presumably for budget reasons, as noted the book does not include reproductions of Shulz’s work (save for cover and end sheets). The rights for publication might have been prohibitive. Presumably, United Feature Syndicate is still cleaning up on Peanuts licensing. But given my druthers, I would choose a third to half of these essays for more capacious treatment, add illustration to facilitate visual argumentation, and design for a scale bigger than the 5.5 x 8.5 inches of this edition. That would be a somewhat more serious book than this one, a special publication of the Library of America.