In 1958, when Morgantown, West Virginia, native Don Knotts (1924-2006) made a guest appearance on the TV sitcom Love That Bob, he had become a fairly established comic actor. He had appeared on Broadway in 1955 in the hit show No Time for Sergeants, which ran for 796 performances, where he met Andy Griffith. “Andy and Don quickly grew close,” writes Daniel de Visé in Andy & Don, “Don admired Andy’s abundant talent, and Andy came to adore Don’s sweet vulnerability.” Knotts reprised his small but memorably funny role in the 1957 film version of Sergeants, (as did Griffith with the lead.) Knotts and Griffith went their separate ways once Sergeants ran its course. Knotts went on to become a regular on The Steve Allen Show, a variety show that had elements of The Tonight Show, for which Allen was the founding host, and Saturday Night Live. Earlier in the 1950s, Knotts had worked in radio and television in a show called Bobby Benson and the B-Bar-B Riders. He had started out in show business as a teenaged ventriloquist (inspired as many young ventriloquists were by the wildly successful Edgar Bergen) but threw that over quickly while stationed in the Pacific during World War II, when he discovered that he wanted to do comedy and did not want to be tied to a dummy.

Love That Bob featured Bob Cummings—best known for his roles in Kings Row (1942) and The Saboteur (1942), but who was no longer movie star material—as a playboy cheesecake photographer (a variant of the character Ronald Reagan played in the 1949 comedy, The Girl From Jones Beach). It co-starred Ann B. Davis as his assistant, Schultzy, Rosemary DeCamp as his sister, and DeWayne Hickman as his nephew. In the episode “Bob and Schultzy at Sea ” Knotts plays a shy, sexually unaggressive man on a cruise who is hoping to find a girlfriend. Cummings’s character tries to match him with Schultzy, who is not attractive and who is also desperate to find a mate. Many of the features that are to make Knotts a master comic actor are displayed in the episode—the scrawny physique that is so comically expressive, the plaintive voice that blends pathos and complaint, the face that borders on crushing defeat, but elicits understanding and even gratitude, rather than condescension, from the audience. He must play his physical weakness and his passive yet pronounced sexual yearning against Schultzy’s physical strength—Ann B. Davis picks up Knotts in one hilarious scene—and her aggressive and oafishly desperate sensuality. Her performance is very good. But it is Knotts who is masterful in a highly forgettable television program, a performance that outlines some of the building blocks that Knotts will use to make the unforgettable character Barney Fife, who made The Andy Griffith Show such a wonderfully wrought specimen of great television comedy.

As Griffith told the William Morris Agency, “I’ve struck out in movies and now on Broadway, and I don’t want to go back to nightclubs, so maybe I’d better try television.” So, The Andy Griffith Show was launched in 1960.

By 1958, Mount Airy, North Carolinian Andy Griffith (1926-2012) was already a movie star, having played the lead in the Elia Kazan/Budd Schulberg satire of a charming, seductive, ruthless, and power mad country raconteur and singer in A Face in the Crowd (1957) and having reprised his Broadway role in the film version of No Time for Sergeants (1957). Griffith, unlike Knotts, skipped military service during the war, for which he would be criticized by many veterans for the rest of his life, and unlike Knotts, was reared in more pampered surroundings. Both Knotts and Griffith seemed to have been driven in emotionally similar ways to performing: “One thing we’ve talked about a lot is the way a comedian is born,” de Visé quotes Griffith, “Don says a comedian is born out of either unhappiness or embarrassment, and at some time in life, perhaps when you’re about three or five years old, you start to learn to protect yourself. When you’re laughed at, you turn it to your advantage.” And both men were laughed at as children. Griffith was never much academically in school but he liked performing and developed his talents as a singer and storyteller at the University of North Carolina. He and his first wife, Barbara, a singer, were a duo for a time but Griffith caught on with his Southern storytelling, particularly his routine about being a country boy watching a football game for the first time. His success led to his wife’s considerable unhappiness and slowly, but inevitably, destroyed their marriage. But in 1957 after this huge splash with two hit films, there was no place to go for Griffith but down, unable to get any roles but variations of Sergeants uncouth Southern country boy Will Stockdale and failing at being a nightclub performer who mixed singing with stand-up comedy. He failed in his return to Broadway in the musical Destry Rides Again. As he told the William Morris Agency, “I’ve struck out in movies and now on Broadway, and I don’t want to go back to nightclubs, so maybe I’d better try television.” So, The Andy Griffith Show was launched in 1960.

When Knotts heard about Griffith getting his own television show playing a small-town sheriff, he immediately called his old friend and asked, “Don’t you think Sheriff Andy Taylor ought to have a deputy?” And one of television’s greatest comic partnerships was born.

It made sense for the producers to redesign the show around the relationship between sheriff and deputy, Knotts and Griffith, once it was apparent how well the two men worked together, how effective Griffith was as the wise, if occasionally exasperated straight man to Knotts’s manic, officious, incompetent but lovable sidekick. This set up (the show originally was meant to focus on Griffith’s character relationship with his son, Opie, played by Ron Howard) meant that the show could do a sort of parody of the relationship between actors James Arness and Dennis Weaver in Gunsmoke, the most popular western, and one of the most popular shows on television at the time. Arness played the wise and brave Marshal Dillon to Weaver’s drawling, incompetent but well-meaning, gimpy-legged deputy Chester. The Andy Griffith Show did a subtle reversal, not having Griffith wear a sidearm while Knotts did (usually recklessly and comically displaying it). On Gunsmoke, it was the opposite, Arness wore the sidearm while Chester went unarmed.

No one watched Griffith, not in my home or any other black homes I knew. I was able to watch it as a child only when I was home sick from school … and alone because my mother was at work. (My mother and sisters never liked it.) Reruns of the show were broadcast in the morning. That is how I learned to love a show that I was fairly sure did not love me.

Also, making the pairing of Griffith and Knotts the imaginative fulcrum of the show intensified its Southern sensibility. What drew Griffith and Knotts together as young actors in the 1950s were their roots. “Andy and Don traded stories of the Old South, of dusty towns filled with old men whittling outside country stores, of lonely widows pickling cucumbers for the state fair, of lazy evenings spent strumming guitars and singing hymns on the front porch,” writes de Visé. And this is precisely the nostalgic, serene South that Mayberry, the fictional North Carolina town that served as the show’s setting, became: the folksy, child-filtered, imaginary south of the two men whose relationship defined the show. This is not to say that Mayberry did not have its quirks, as de Visé writes:

“ . . . there was a distinct dearth of traditional families in this quintessential family show. Andy was a widower, Barney a bachelor, Aunt Bee a spinster. Floyd the barber and Otis the drunk both purportedly had spouses, but they were rarely seen. The lesson of Mayberry, Ron Howard later asserted, was that “a community could be a family. The town of Mayberry is one big family.”

There was something about Mayberry that evoked a kind of Southern nowhere-ness. It was the not really the New South of Henry Grady, not the romanticized South of a natural and benign unequal social order of Thomas Nelson Page. How could Mayberry be that when it had, amazingly, no black people? It was certainly not the complex, half-crazed South of W. J. Cash. Mayberry was an idealized WHITE South but it was not exactly the South of the Agrarians, although it might have been closest to that in some respects. As de Visé states:

“Part of the program’s unique appeal was its pleasing invocation of simple virtues in a turbulent time. The Andy Griffith Show was anachronistic. The denizens of Mayberry wore clothing of uncertain vintage and hair of indeterminate style and drove cars of unspecified age. Scant mention was made of current affairs or changing times. Telephone calls were placed through a human operator, and no one seemed to own a television set.”

Of course, the show was a response, a reaction to its time. As The Civil Rights movement was going full bore in the South during the years the show ran (1960-1968). When the old racist, segregationist order was challenged and finally overthrown, The Andy Griffith Show was in part about whites being able to imagine a South WITHOUT blacks, a world without blacks. (A South without blacks, to be sure, ceased to be the South in any meaningful way, a fact that white Southerners simultaneously can and cannot acknowledge, trying, as they are, to free themselves from the dense historical web of their own complex fate.) In this way, the show was, more so than other all-white television programs of the time, an escape from blacks. Perhaps it was because of the show’s remarkably powerful and effective evocation of a placid and touching white South that made it unpopular with the blacks I knew, who certainly knew better than to accept any crap like that. It was not because it was a white “hillbilly” show that the blacks I knew did not watch it. Most of them loved The Beverly Hillbillies (1962-1971, especially the character of Granny) which ran during the same years as The Andy Griffith Show. But no one watched Griffith, not in my home or any other black homes I knew. I was able to watch it as a child only when I was home sick from school (which was fairly often during my elementary school years) and alone because my mother was at work. (My mother and sisters never liked it.) Reruns of the show were broadcast in the morning. That is how I learned to love a show that I was fairly sure did not love me.

What I saw in The Andy Griffith Show as a child was not the wish of a white South made wholesome, but rather the imaginary pull of community as a kind of blessing. I placed Mayberry over my South Philadelphia neighborhood and through that prism, my school and my teachers, the working-class Italian shopkeepers I knew, the Jewish clothing merchants, the black boys I played ball with and prowled the Italian market with, hustling shopping bags and toting services to the women shoppers; this entire world became my Mayberry, the adults and children I interacted with were my family. The intensity with which I projected the show into my own life (any show about a father and a son for a fatherless boy like me was bound to be a kind of catnip, in any case), projected as my own life, is, in retrospect, astonishing to me. I decided as a child, unknowingly, that I would love The Andy Griffith Show not in spite of my race, but because of it. I felt I knew and needed that idyll more than the whites for whom it was made. The Andy Griffith Show convinced me that, despite my poverty (I was the poorest kid among the poor kids I knew), I had a wonderful childhood. And that revelation was, in fact, the truth.

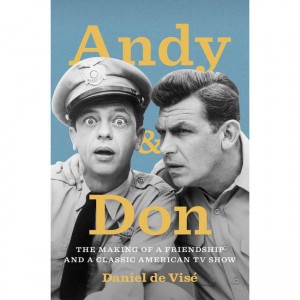

Of the more than seven or so books on The Andy Griffith Show, Andy & Don is, for this reader, the best, the best written, the best in evocating what the show meant to the culture at large. It provides a detailed account of the show’s run, spotlighting certain key episodes. The first five years of the show, the years Knotts was co-star as Barney Fife, were clearly the best. The Andy Griffith Show declined precipitously after that, becoming embarrassingly and clumsily white when, ironically, the show switched from black and white to color. Knotts won five Emmys for his performances on the show. Griffith did not win any, was not even nominated. This was probably a source of tension between the two men, although Griffith did his best to hide it. (Griffith blocked having a statue of Knotts erected in Mount Airy, Griffith’s hometown and now “Mayberry USA,” although there is one of him in character with Opie. He also blocked erecting a statue of Knotts in Knotts’s hometown of Morgantown, West Virginia. It is hard to discern if jealousy or something else motivated Griffith.)

What I saw in The Andy Griffith Show as a child was not the wish of a white South made wholesome, but rather the imaginary pull of community as a kind of blessing. I placed Mayberry over my South Philadelphia neighborhood and through that prism … this entire world became my Mayberry, the adults and children I interacted with were my family.

Knotts went on to appear in several children’s films, including partnering with Tim Conway in The Apple Dumpling Gang and its sequel for Disney. (I remember these Knotts films being popular with the children, both black and white, that I grew up with.) Knotts was also featured on the successful 1980s sitcom, Three’s Company (1977-1984). Griffith starred in several television movies after The Andy Griffith Show, playing characters he thought would erase the image of the benevolent Andy Taylor from the public’s mind. He ended his professional career as the successful defense lawyer, Matlock, in the series of the same name (1986-1995). He brought Knotts into the show, but they were unable to repeat the magic they had in The Andy Griffith Show. The two men remained close friends until the death of Knotts in 2006.

Both men had their personal demons. Each was married three times, had their share of affairs and problems with their children. Both were heavy smokers; Griffith was also a hard drinker, who physically abused his first wife; Knotts was a hypochondriac and a loner. Fame is not always what it is cracked up to be. And as soul singer James Brown once sang, “Money won’t change you.” It will just make you more of what you are. Most episodes of The Andy Griffith Show can be found on YouTube, and I strongly recommend seasons 1 through 3. Those episodes are simply some of the best we have from the golden age of television. I also recommend Andy & Don as one of the best accounts of one of the best and most reactionary television shows there ever was, or ever will be.