If one definition of city life is the population of space on a massive scale, or at least people living in close proximity, then it makes sense that some of the best music and songs about city life have been given to us in the form of popular music. Or, put another way, is there any other living arrangement more demonstrably popular, more “pop” and rock ’n’ roll, than city life?

Earlier this year Gerald Early, editor of The Common Reader, offered his own personal list of noteworthy songs about cities and urban life. It is in this spirit that this second installment follows, albeit with a heavy debt of choices inspired by the words of Italo Calvino from Invisible Cities:

The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.

Songs and music give tangible form to the invisible by making the invisible audible, and therefore visible in our hearts and minds. Listening to music, we travel in our minds. Hopefully, the following songs and music give ample space only to some of the best songs of all time.

• • •

Charles Dickens found the metropolis suitable for one of his most famous titles, as no two cities embodied the bridge between the stability of tradition and the dangers of revolution better than London and Paris. So it is with songwriters.

The French no doubt have their own favorites but, la tradition nationale soit maudite, what matters here is the English-speaking world. Cole Porter first struck what was arguably melodic gold with his 1953 song “I Love Paris,” a song that floats so effortlessly above the seasons it chronicles that the listener almost feels transported. Ella Fitzgerald recorded the best version, or one at least more elegiac and with more emotional resonance than the swinging, up-tempo version delivered by Frank Sinatra. Flash forward sixty years and we hear that Lana Del Rey sided with Fitzgerald’s choices of tone and delivery for a short live performance during a stop at Paris’s Olympia during her 2013 European tour. Few versions of a classic song have been so simultaneously modern and retro.

The French no doubt have their own favorites but, la tradition nationale soit maudite, what matters here is the English-speaking world. Cole Porter first struck what was arguably melodic gold with his 1953 song “I Love Paris,” a song that floats so effortlessly above the seasons it chronicles that the listener almost feels transported. Ella Fitzgerald recorded the best version, or one at least more elegiac and with more emotional resonance than the swinging, up-tempo version delivered by Frank Sinatra. Flash forward sixty years and we hear that Lana Del Rey sided with Fitzgerald’s choices of tone and delivery for a short live performance during a stop at Paris’s Olympia during her 2013 European tour. Few versions of a classic song have been so simultaneously modern and retro.

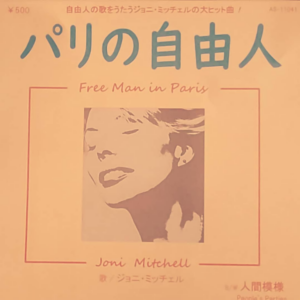

Joni Mitchell approached “The City of Lights” as the ultimate escape from the business pressures of the Anglo world. A subtle biography of her friend and music industry executive David Geffen, “Free Man in Paris” has all the insouciante elegance of a stroll down the Champs-Élysées, replete with a buoyant flute line. It is a song about the liberating power of great cities everywhere. British indie band Friendly Fire could not care less about its therapeutic powers. The percussive point of their 2007 song “Paris,” is about making it big enough to live there full-time. The song throws the intriguing twist of not being sung to a paramour, but a best friend: “I’ll find you that French boy / You’ll find me that French girl.”

Where Paris is romantic and shimmering London, by contrast, cannot help but be shabby and a bit depressing. For The Clash, make that downright apocalyptic. Copping the BBC’s famous World Service station ID, “London Calling” depicts the British imperial capital as the besieged center of nuclear Armageddon, thinning wheat, police brutality, dead engines, and an overflown Thames, all beckoning “the zombies of death.” London not as center of the world, but the End of the World. Fifteen years later, in 1994, Blur would paint this same city as an ultimate metropolis of excitement, but also an ultimate challenge of survival, wrapped in mystery. “London Loves,” the song and its chorus proclaim. But do you have it in you to love it enough in return? Years before either of these takes was The Kinks’s 1967 “Waterloo Sunset,” a song so beguiling it turns a view of the Thames from a drab tube station stop into the very picture of paradise. No less than British novelist Zadie Smith name-dropped it in her 2000 debut novel White Teeth while Robert Christgau, once christened “dean of American rock critics,” declared it nothing less than “the most beautiful song in the English language.” The rest of America, alas, never did understand. The song failed to chart at all on U.S. hit lists.

John Cale

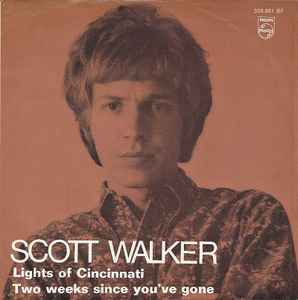

Other European cities have had their moments in song as well, but to understated, often devastating, effects. John Cale, a smoldering Welshman made most famous by his turn on viola, bass, and guitar with The Velvet Underground composed “Amsterdam,” one of the most delicate and heartfelt love songs to a woman whose love the singer knows he has, in fact, lost. When Cale sings softly, “I do believe the journey did her well” the impact is almost overwhelming. Not nearly as dramatic is Belgian Jacques Brel’s take on the city, but it could be argued that “Amsterdam” is more about a port sailor than the Netherlands’ capital. To judge for yourself, take in either David Bowie’s or Scott Walker’s cover versions.

Walker, who changed his name from Engel to make his UK mark with two other fellow Yanks as part of The Walker Brothers, was himself no slouch when it came to his own favorite city. “Copenhagen,” much like Porter’s “I Love Paris,” traces its city through the seasons, albeit with more musical and lyrical flair by way of his silky, golden baritone. For a native American, Walker’s style is decidedly European. If that strikes Porter connoisseurs as sacrilege, they might want to listen to it with images to match Walker’s vision. Walker’s other homage to city life, “The Lights of Cincinnati,” is not nearly so magical, having been written by the English team of Tony Macaulay and Geoff Stephens. But for an ex-pat in Europe how could an Ohio city possibly compare with Denmark’s capital?

Walker, who changed his name from Engel to make his UK mark with two other fellow Yanks as part of The Walker Brothers, was himself no slouch when it came to his own favorite city. “Copenhagen,” much like Porter’s “I Love Paris,” traces its city through the seasons, albeit with more musical and lyrical flair by way of his silky, golden baritone. For a native American, Walker’s style is decidedly European. If that strikes Porter connoisseurs as sacrilege, they might want to listen to it with images to match Walker’s vision. Walker’s other homage to city life, “The Lights of Cincinnati,” is not nearly so magical, having been written by the English team of Tony Macaulay and Geoff Stephens. But for an ex-pat in Europe how could an Ohio city possibly compare with Denmark’s capital?

Berlin, that beleaguered German capital first soaked in decadence then transformed into the headquarters of European fascism before being bombed into oblivion and then split in two and reunited before the century’s close, may seem the unlikely inspiration for song given its multitude of identities. Then again, the power of an identity crisis is hard for a songwriter to resist. This sprawling Prussian-German metropolis was a compositional palimpsest for the talents of Kurt Weil—despite the fact that his most famous work, The Threepenny Opera, was set in Victorian London—who wrote “Berlin Im Licht.” The song is as short as Berlin is big and wide, drawing a portrait of a city so dark not even the sun can reveal it.

The famous 1966 musical “Cabaret,” meanwhile, celebrated Berlin’s banner days of sexual and artistic freedom just before the end of the Weimar era. For the best single takes after Weil, Marlene Dietrich was one of the first in line with “I Still Have a Suitcase in Berlin (Ich Hab Noch Einen Koffer in Berlin),” in which her husky and forward, yet eerily distant, voice wraps up a charming song about how one object can carry so many leftover feelings, yet also leave many emotions of the heart behind. For Lou Reed, who lead the aforementioned Cale as the songwriter behind New York City’s Velvet Underground, Berlin was more of an emotional landscape than mere metropolis. Berlin was the title of a whole album’s worth of songs and a title track itself. Reed’s third solo album since the disbanding of The Velvet Underground, Berlin takes in romance, betrayal, suicide, drug addiction (a Lou Reed specialty), and a wrenching song of children torn from their mother. Not for the faint of heart. Reed proudly admitted he had never been to the city. Artist and film director Julian Schnabel captured Reed’s celebrated live performance, Berlin: Live at St. Ann’s Warehouse, in Brooklyn 2008. David Bowie, too, saw the city mostly in terms of lost hope, but also a city with spirits potent enough to stoke an everlasting, defiant romance. “Heroes” never once calls the city by its name, but the song’s clear reference to the Berlin Wall that supposedly separates two lovers, plus the fact that it was recorded in West Berlin’s Hansa Studio 2 is all you need know. With the possible exception of Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA,” the song is arguably the closest pop music has ever gotten to sounding truly anthemic without also sounding naif or cheesy. It has also been a staple of teenage bedrooms ever since it was unleashed upon the world in 1977. The same album named after the track itself also contains “Neuköln,” an atmospheric instrumental in homage of what was then West Berlin’s southeast neighborhood. Featuring Bowie on saxophone, the song inaugurated several of the pop star’s emergent “mood pieces,” but also tried to capture the ethnic feel of the city neighborhood, then home mostly to Berlin’s Turkish community.

If Berlin was a destination for Bowie’s talents, he had plenty of stops along the way. Before the LP Heroes there was “Warszawa,” another mostly instrumental “mood piece” recorded earlier that same year, 1977, albeit sung in some fantastical made-up language Bowie said was inspired by an album of Polish folk songs he purchased in Warsaw. Regardless of inspiration, fans loved its vivid evocation of the urban, Cold War landscape. And once the Warsaw Pact itself disintegrated city artists celebrated the British pop star with his own city mural.

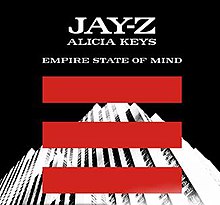

Moving across the Atlantic, and into more recent times, Jay-Z and Alicia Keys gave the Big Apple arguably its finest tribute, or at least the finest in rap and hip-hop ode, with their 2009 single “Empire State of Mind.” As big as Keys’ soaring chorus is, Jay-Z still cannot resist name-dropping Sinatra’s anchoring anthem: “I’m the new Sinatra, and since I made it here I can make it anywhere.” Before the critical and commercial success of this song, many would argue that Digable Planets got there first with “N.Y. is Red Hot,” a tour of the city as smooth as a Sunday walk through Central Park, a metropolis more mellow than all-out hustle. The cerebral mind of Leonard Cohen cast a cynical eye on the city with “First We Take Manhattan.” While not immediately memorable as Cohen’s best songs, its arch lyrics and sense of menace enflamed fans’ imaginations. Cohen settled the argument when he admitted, a full thirteen years before 9/11, that it was a song laden with references to terrorism. Initially gifted to U.S. singer Jennifer Warnes in 1986, Cohen coined his own version the following year, with college-rock superstars R.E.M. not far behind in 1992.

Moving across the Atlantic, and into more recent times, Jay-Z and Alicia Keys gave the Big Apple arguably its finest tribute, or at least the finest in rap and hip-hop ode, with their 2009 single “Empire State of Mind.” As big as Keys’ soaring chorus is, Jay-Z still cannot resist name-dropping Sinatra’s anchoring anthem: “I’m the new Sinatra, and since I made it here I can make it anywhere.” Before the critical and commercial success of this song, many would argue that Digable Planets got there first with “N.Y. is Red Hot,” a tour of the city as smooth as a Sunday walk through Central Park, a metropolis more mellow than all-out hustle. The cerebral mind of Leonard Cohen cast a cynical eye on the city with “First We Take Manhattan.” While not immediately memorable as Cohen’s best songs, its arch lyrics and sense of menace enflamed fans’ imaginations. Cohen settled the argument when he admitted, a full thirteen years before 9/11, that it was a song laden with references to terrorism. Initially gifted to U.S. singer Jennifer Warnes in 1986, Cohen coined his own version the following year, with college-rock superstars R.E.M. not far behind in 1992.

Moving south to New Jersey, Bruce Springsteen gave his home state a rustic ballad of stasis and decay waiting on hope with “Atlantic City.” Where The Boss’s debut album Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J., at least hinted at tones of absurdist humor, this 1982 song cast its waning endurance to fates unknown: “Everything dies, baby, that’s a fact, but maybe everything that dies someday comes back.”

Further south to Maryland, Prince unveiled a rare sense of political urgency with his 2015 anthem, “Baltimore.” Penned in the wake of Freddie Gray’s death in the custody of Baltimore Police, it is tempting to declare it “Best BLM Song of All Time!” At a minimum, it is doubtless the most impactful song Prince wrote before his 2016 death.

Further south to Maryland, Prince unveiled a rare sense of political urgency with his 2015 anthem, “Baltimore.” Penned in the wake of Freddie Gray’s death in the custody of Baltimore Police, it is tempting to declare it “Best BLM Song of All Time!” At a minimum, it is doubtless the most impactful song Prince wrote before his 2016 death.

Further south still to Florida, and twenty-five years before he was known for his Academy Awards slap, Will Smith was all about a good, rollicking getaway with “Miami.” Drawing from his performance chops as Fresh Prince, Smith deftly split the song between funky disco and Caribbean rhythms. More fun than it has any right to be, and the Miami Convention & Visitors Bureau could not possibly ask for more. No one can say U2 did not try to capture the city’s spirit with their own “Miami,” but even if the song marked a musical departure from the band’s expected style, all the earnest Irishmen really had to talk about was glancing impressions and buying suits. Gente De Zona’s “La Gozadera” is the perfect antidote, pulling in all of Miami’s diverse Latinx heritages for one big party. The city’s name might not live in the title, but from the very first line up to the last, there is no mistaking what this song is about: “Miami me lo confirmó! (Miami confirmed it for me!).” Can more than 1.4 billion YouTube views possibly be wrong?

The City of Big Shoulders has more than its share of blues and rock homages. Take your pick, from “Meet Me in Chicago,” by Buddy Guy, to “Chicago Bound” by Jimmy Rogers to “Sweet Home Chicago,” by Robert Johnson, and alternate versions by Eric Clapton and The Blues Brothers. Sufjan Stevens’s 2005 song “Chicago,” drawn from his LP lllinois, part of Stevens’s “Fifty States Project” promising to write and produce an album inspired by every U.S. state, stands out for its indie genre apart from rock and blues even if, like its more famous predecessors, it too is mostly about getting there. Stevens does not sing his song, so much as confess it. And few horn sections have sounded so simultaneously modest and majestic. This is the sound of the Midwest’s biggest city in full bloom, and full of second chances.

Matters are a little different eastward, in Detroit. The auto industry makes life a little louder, with the economic fall-out of the 1980s making life after the boom times more tenuous. Listening to Gil Scott-Heron’s elegiac 1977 take, “We Almost Lost Detroit,” it seems he could see the city’s descent years it would crash in grand style: “It stands out on a highway / Like a creature from another time.” David Bowie’s earlier, 1973 song “Panic in Detroit” is said to have borrowed his friend Iggy Pop’s stories and experiences living there in 1967, the year of the Detroit riots. A showcase for guitarist Mick Ronson, it also borrowed heavily from the style and rhythms of Bo Diddley.

Born and mostly based in small-town western Oklahoma, songwriter Jimmy Webb never performed his own songs to fame. Glenn Campbell did that for him, with various cities marking Webb’s emotional landscapes behind him. First up was “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” in 1967. The city of the song’s title was of course real, but not as real as its story of an impending break-up. (Soul singer Isaac Hayes adored Webb’s song so much he stretched it out to a full nineteen minutes, including a nine-minute backstory that was all his own.) “Wichita Lineman” followed the year after, prompting millions of radio listeners to park their cars roadside for a deeper listen whenever it hit the airwaves. Today it is best to forget that Webb’s song and Campbell’s rendition was selected in 2019 by the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry for its “cultural significance” and just imagine you are hearing its solemn tale of solitude again, for the first time. “Galveston,” the last of the great Webb-Campbell song collaborations about place, and a seemingly breezy take on a U.S. soldier’s homesickness while serving in Vietnam, could not match the height of its predecessors, never mind that it rose straight to No. 1 on the country charts the year of its release in 1969.

Born and mostly based in small-town western Oklahoma, songwriter Jimmy Webb never performed his own songs to fame. Glenn Campbell did that for him, with various cities marking Webb’s emotional landscapes behind him. First up was “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” in 1967. The city of the song’s title was of course real, but not as real as its story of an impending break-up. (Soul singer Isaac Hayes adored Webb’s song so much he stretched it out to a full nineteen minutes, including a nine-minute backstory that was all his own.) “Wichita Lineman” followed the year after, prompting millions of radio listeners to park their cars roadside for a deeper listen whenever it hit the airwaves. Today it is best to forget that Webb’s song and Campbell’s rendition was selected in 2019 by the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry for its “cultural significance” and just imagine you are hearing its solemn tale of solitude again, for the first time. “Galveston,” the last of the great Webb-Campbell song collaborations about place, and a seemingly breezy take on a U.S. soldier’s homesickness while serving in Vietnam, could not match the height of its predecessors, never mind that it rose straight to No. 1 on the country charts the year of its release in 1969.

Nearby Houston, the Texas metropolis that mushroomed almost overnight thanks to oil, may not seem like much for music inspiration, but Iggy Pop found the climate remarkable all the same. “Houston is Hot Tonite” is remarkable more for its insight into the primal forces of oil— “I don’t mind, a bloodbath, when I’ve got oil, on my breath” than anything else. For a view to the city’s dynamism and subterranean thrills, Dizee Rascal’s “H-Town” is hard to beat: “The party’s never done / We just take it to the parking lot, and then we laugh a lot, until they call the cops, yo.” Just forget that Dizzee grew up in the UK, and you are right there with him.

It seems strange to acknowledge that it was a gritty punk band, and not Randy Newman’s far more famous “I Love L.A.,” that first set the “City of Angels” dead to rights. Then again, Randy Newman was far too busy writing endless streams of film scores before he would take his rightful turn in 1983, rubbing the faces of every East Coaster and Midwesterner in the fact that, at least where he lives and works, “the sun is shining all the time.” X could not possibly care at all, having written a whole album’s worth, fittingly titled Los Angeles, about the hidden lives, shadowy fears, and fleeting thrills of the late 1970s L.A. they knew just as well, if very differently. The harrowing title track is about the nightmare of trying to escape a city you loathe, but cannot bring yourself to leave. And the song’s explicit co-opting of racist sentiments—“She started to hate every nigger and Jew / Every Mexican who gave her a lot of shit / Every homosexual and the idle rich”—on the part of its central character still shocks. “City of Angels” this ain’t.

Northward, San Francisco has been chronicled so many times thanks to hippies and flower children that it is hard to find a song about its true, current status as a metropolis almost no one else besides billionaire hipsters can afford. Fulfilling the dictum that sometimes outsiders see better than insiders, Sheffield UK’s Arctic Monkey do that trick, and then some. “Fake Tales of San Francisco” trolls all the ways the super-cool-status of any mythically cool city can spawn embellished anecdotes and even outright lies. The ultimate, anti-hipster anthem about owning up to where you are from, even if it is just Hunter’s Bar or Rotherham in sleepy Old England.

Coda

Cities exist on maps, but also in the mind. In that vein, there is a unique category of songs about urban centers as ideas, fears, states of mind. Whole lists of cities could be rattled off in the lyrics, or none at all. What concerns the songwriter is the urban center as a personal ideal, a Platonic form that we might grasp at, but never attain, much less ever live in.

Talking Heads embodied this notion better than any other band or songwriter before them, harnessing bandleader David Byrne’s signature way with of writing lyrics that describe universal feelings in peculiar ways. “Cities,” drawn from the band’s 1979 album Fear of Music, name-checks only London, Birmingham, El Paso, and Memphis (both in Egypt and Tennessee), but it is not about the cities themselves, but the self-conscious act of finding or choosing the best place to live. It is a song both matter-of-fact, yet oddly profound.

Talking Heads embodied this notion better than any other band or songwriter before them, harnessing bandleader David Byrne’s signature way with of writing lyrics that describe universal feelings in peculiar ways. “Cities,” drawn from the band’s 1979 album Fear of Music, name-checks only London, Birmingham, El Paso, and Memphis (both in Egypt and Tennessee), but it is not about the cities themselves, but the self-conscious act of finding or choosing the best place to live. It is a song both matter-of-fact, yet oddly profound.

By contrast, “I Love Living in the City” by Fear is the dreaded flipside of not being able to choose where you live at all, but still choosing the laughter of the damned. The climax of Penelope Spheeris’s 1981 documentary on the Los Angeles punk-rock scene, The Decline of Western Civilization, this song helped cement irony and disgust as enduring parts of the punk ethos. Not fun, and not pretty, but worth a listen if you like dark humor.

The Gun Club’s “Sleeping in Blood City” continues along the same vein, but with true romance coursing through its veins. A blistering track from the band’s Miami LP, singer Jeffrey Lee Pierce imagines forbidden love in an imaginary city that could be located anywhere but lives especially in the fevered, male mind.

Finally, a song that name-checks three major cities, but still manages to be a song encompassing love and all the world. A tall order? Certainly. But if one song does that, it must be Vampire Weekend’s “Jerusalem, New York, Berlin.” It could be argued that the song’s sentiment is too large for its admittedly humble accompanying music. Still, if you do not feel yourself near tears upon hearing the third chorus of “Oh, wicked world / Just think what could have been / Jerusalem, New York, Berlin” you probably have a heart of stone.