Writing for Justice: Victor Séjour, the Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara and the Age of Transatlantic Emancipations

If composer Lin-Manuel Miranda had read the biography of 19th-century Creole of color Victor Séjour (1817-1874), we might be humming a catchy complex rap refrain from Séjour. Like Alexander Hamilton, Victor Séjour’s origins were humble and his success all but unimaginable. Unlike Hamilton, Victor Séjour’s success as one of the most popular playwrights of mid-19th century Paris would have been impossible in his native land. For more than a century most of Victor Séjour’s work had not been translated into English; currently just three of his 22 plays and a short story are available in English. And despite the recent trend in American scholarship emphasizing the transnational and cross-cultural dimensions of American culture, Victor Séjour is rarely mentioned. Elèna Mortara’s Writing For Justice: Victor Séjour, the Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara in the Age of Transatlantic Emancipations addresses this gap by placing Séjour and his work in the context of international cultural expressions that championed emancipation movements throughout the 19th century. Writing for Justice’s transnational lens illuminates the reasons for which Victor Séjour, a Catholic and Creole of color from Louisiana, was moved to write a play based on the kidnapping of a Jewish boy by the Catholic Church. In the American South slave children were routinely taken from their parents; it was practice protected by law. What better figure through which to explore the transnational representations of social injustice than of a stolen child?

Victor Séjour was born in 1817 into the volatile world that the American, French and Haitian Revolutions had created. Refugees from the Haitian Revolution, such as Séjour’s father Louis, doubled the French-speaking population of Creoles of color in New Orleans. Although many of Louisiana’s men and women of color were free, in the three decades leading up to the Civil War, their civil rights were increasingly circumscribed. In 1836, 19 year-old Victor Séjour left New Orleans for Paris and never looked back. In 1837 his first publication, “The Mulatto” appeared in a French abolitionist journal. It was the first short-story published by an American of African descent. And in 1844 Séjour’s first play, The Jew of Seville was accepted by the national theater of France, the Comédie Française. It was an auspicious start for the 26 year-old American. Over the next 15 years, Séjour wrote a dozen plays that were performed at Paris’s most popular theaters. By 1858, Victor Séjour was in a unique position to dramatize the kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara.

Six year-old Edgardo Mortara was forcibly removed from his home in Bologna by the Pope’s guards on June 24, 1858. A maid who worked for the Mortara’s claimed that she had baptized him. According to the Church, Edgardo was a Catholic and could not be raised in a Jewish home. The kidnapping prompted near universal condemnation of the Catholic Church and Pope Pius IX. Outraged Jews and non-Jews from Europe and the United States petitioned their governments to persuade the Vatican to rescind the order, but Pius IX remained intransigent. Edgardo Mortara was never returned to his parents. In addition to the violation of the parents’ rights, the kidnapping underscored a vexing geo-political problem. At the center of the liberal efforts (by Garibaldi and Cavour) to unite the regions of the Italian peninsula into a modern state sat, literally and figuratively, the Papal States, where the Pope ruled supremely over matters spiritual and secular. Ultimately the “Mortara affair” served to undermine papal authority and contributed to the eventual success of Italian unification in 1870. The Fortune Teller dramatized the Mortara case and offered a stinging critique of religious intolerance and papal authority.

Writing for Justice weaves several contextual strands into the larger story that illuminates the links between Victor Séjour and Edgardo Mortara. That larger story, as Elèna Mortara suggests, is best described as the Age of Emancipations. She reminds us that proponents of the values of a liberal society—religious tolerance, equality and civil rights—were spread across the European and American continents. Victor Hugo joined Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Thoreau in vigorously opposing John Brown’s death sentence. Margaret Fuller linked the Italian struggle for unification to the struggle for abolition in the American South. The following milestones in that struggle are: in the United Kingdom, The Catholic Emancipation Act, (1829), The Emancipation of Negroes in British West Indies, (1833) and The Jewish Emancipation Act, (1858); in Italy, The Emancipation of Protestants and Jews in Piedmont-Sardinia (1848) and in the United States, The Emancipation Proclamation (1863). Opposition to slavery in the Americas, the Jewish ghettos of Europe, and the failure to extend civil rights to Jews and Protestants in France or to Jews and Catholics in England and to women everywhere, were expressions of a revolution that continues to transform the modern world.

Writing for Justice weaves several contextual strands into the larger story that illuminates the links between Victor Séjour and Edgardo Mortara. That larger story, as Elèna Mortara suggests, is best described as the Age of Emancipations. She reminds us that proponents of the values of a liberal society—religious tolerance, equality and civil rights—were spread across the European and American continents.

Elèna Mortara’s discussion of The Fortune Teller is particularly impressive against this larger background. In the context of Séjour’s earlier work, “The Mulatto” and The Jew of Seville, which spotlight conflict prompted by interracial and inter-religious relationships, the dramatic rendition of the kidnapping was familiar territory. When The Fortune Teller premiered in December of 1859, Séjour had changed key elements of the Mortara story: he placed the drama in the 18th century, made the kidnapped child a female and began the story 17 years after the abduction. In the early weeks of its premiere, the Catholic press was critical of its alleged anti-Vatican stance. In their view, it seemed to have slipped past the censors, was pro-Jewish and therefore anti-Catholic. Napoléon III’s secretary, Jean-François Constant Mocquard, had collaborated with Séjour and this, coupled with the Emperor’s attendance on opening night, indicated his approval of the play’s explicit criticism.

Elèna Mortara’s review of the critical reception of The Fortune Teller is lucid and comprehensive. She examines the contemporary criticism, sorting through the thorny political questions. She also notes translations of the play into Italian, German and English as well as performances in Belgium, England, Italy and the United States. She illuminates a curious audience response to a performance in Turin in 1860. In English there were at least two versions of The Fortune Teller each with a new title: The Abduction of the Jew’s Child!; or, The Fortune Teller! and The Woman in Red). In these “free adaptations” (meaning not particularly faithful to the original text) characters were added and endings given new twists. Although some “free” English versions acknowledged Séjour’s authorship, some did not. Laxity in international copyright law made such alterations, without the author’s permission or even his knowledge, common.

One especially exciting discovery is an American adaptation entitled, Gamea; or, The Jewish Mother which premiered in New York in 1863. Elèna Mortara’s source for this information is an 1867 article in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine by Olive Logan, an American actress and friend of Jean-François Mocquard. Logan credited Mocquard as the author although acknowledged that Séjour was an “able collaborator.” In 1863 President Abraham Lincoln saw Gamea; or the Jewish Mother twice. In 1865 the play opened at McGuire’s Opera House in San Francisco, in the midst of a public contract dispute between the leading lady and Thomas McGuire, who threatened to “break every bone in her body.” This prompted Samuel Clemens to lampoon McGuire in a “Bereft of bone” verse that was published in the Territorial Enterprise. The Americans who attended performances of Gamea; or, The Jewish Mother did not know that its author was an American Creole of color. Lincoln and Twain would have appreciated that poignant irony.

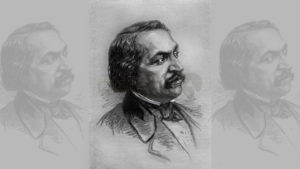

The Fortune Teller, in its several guises, attracted audiences from Paris to London, from Turin to New York, and from Washington D.C. to San Francisco. Now thanks to Elèna Mortara’s careful and painstakingly thorough research we know the extent of its travels. The particular strength of Writing for Justice is the extensive use of several archives. The text includes a comprehensive bibliography that constitutes an invaluable source for future scholars. In addition, Writing for Justice includes a handful of portraits and caricatures of Victor Séjour that appeared in newspapers and journals over the course of his career. These images attest to his popularity and renown. As no photographs of this “Shakespeare of the boulevards” has ever been found, Elèna Mortara’s inclusion and discussion of these images contributes to Séjour’s legacy.

Writing for Justice: Victor Séjour, the Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara in the Age of Transatlantic Emancipations is a deeply felt appreciation for Victor Séjour and The Fortune Teller from a member of the Mortara Family. In the final section of this study we learn that Edgardo Mortara was the great-grand uncle of Elèna Mortara. In particular she points to Séjour’s “Preface” to The Fortune Teller in which he asserts that yes, even as a Catholic, he intended “to plead the Mortara family’s cause.” Most significant for Elèna Mortara was the “… cross-cultural conflict and the predicament of people living across different borders.” Victor Séjour did indeed live that predicament. Writing for Justice is an exemplary instance of scholarship that illuminates the transnational dimension of our history.