Famous actors have a curious, even disquieting, effect upon the mind of their public. They engage in a craft of make-believe, not without the need for both training and talent, necessary for mastering any craft. But it is their power to make the unreal real, make a character on paper actual flesh-and-blood; endow scripted words with the life of true, spontaneous conversation; make the implausible, the ridiculous, the absurd, the dream-like, more immediate, more potent, more enduring, more alive than life as the audience knows it and lives it. It is no original observation to say that actors are illusionists. The trick, the stunt, is to make an illusion seem real while the audience is aware that it is, in the end, an illusion. But the illusion is preferable to reality, so one yearns for the illusion. The romanticism of the yearning becomes as powerful as the illusion itself. Movies are about watching them and yearning for them, either for their past or what the audience hopes will come, mostly both. In this way, actors are like priests and priestesses: the embodiment of paper and fancy, that which sorts out the overwhelming present into a useable past and a prophecy of the future we think we desire. It has made me wonder if Jesus Christ (who made the Word flesh and dwelt among us) was not the greatest actor who ever lived.

• • •

My mother took me to see Dr. No in the year I turned ten years old, the year of the movie’s release, 1962. I had pestered her quite a bit and had hoped that she would take me to the downtown theater where it was playing its first run. But alas we saw it at the Black neighborhood theater in South Philadelphia, where we always went after the A-movies had finished their downtown engagements. It was fine, better than fine, since, in this instance, the patrons did not talk through the film. My mother always took me to the adult showings of movies at the neighborhood theater and the adults talked less than children did. Twice she had taken me downtown to see a movie: William Wyler’s remake of Ben-Hur and Otto Preminger’s Porgy and Bess. For Ben-Hur, I stayed awake for the chariot race; for Porgy and Bess, I fell asleep, after getting beyond the astonishment of seeing an All-Negro cast in Technicolor, which took, perhaps, ten minutes, once I understood that all the actors were going to do was to sing songs I could not understand. She thought they were special and for some reason took me with her. She wanted to take me downtown to see Cecil B. De Mille’s The Ten Commandments but never could manage it. Despite the sex and violence of Dr. No, she did not think I was too young to see the movie. For me, there was no point to a movie but the sex and the violence. I never liked so-called children’s movies much as a kid.

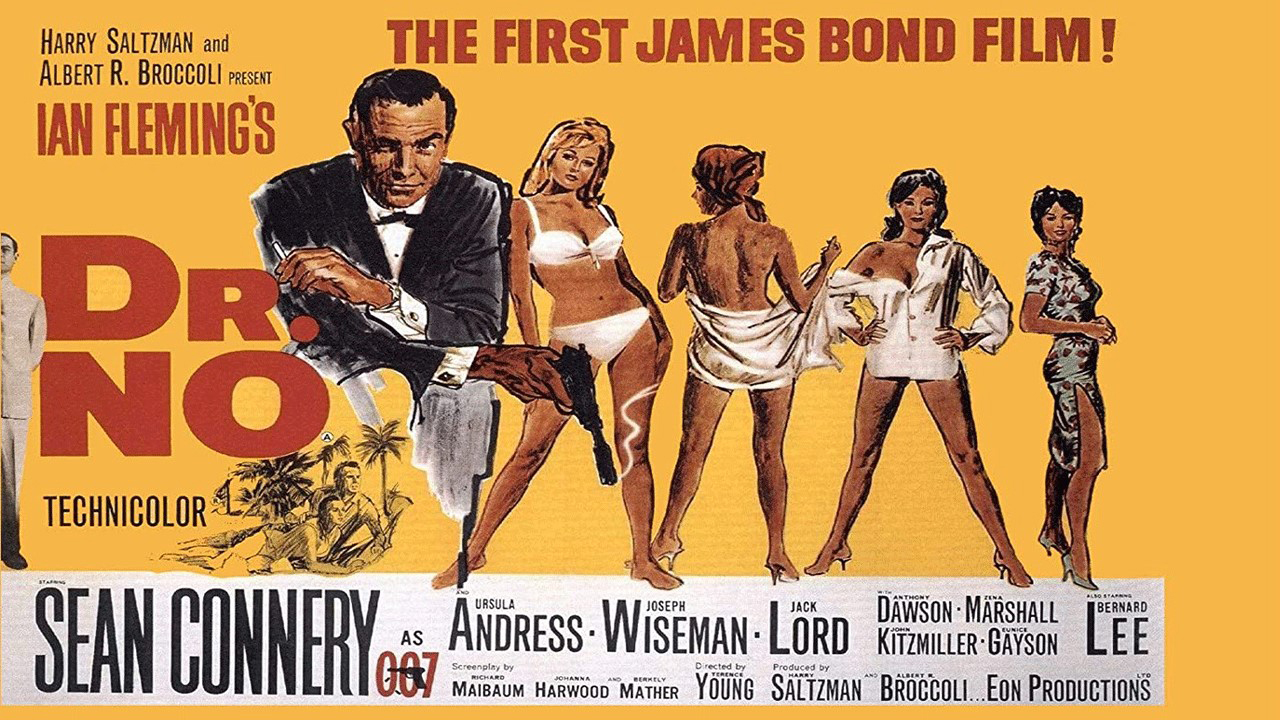

As a boy, I judged movies by their newspaper ads, and no ad excited me as much as the one for Dr. No. The title of the movie itself was intriguing. Who is Dr. No? There was the line about the film being “the first James Bond adventure.” Who is James Bond? Then there was the brief description of “his code 007. The double “0” means he has the license to kill when he chooses … where he chooses … whom he chooses!” What kind of character is this? He can kill anyone he wants? Who gave him the license to kill? Can somebody really give a person the license to kill whomever they wanted, like a driver’s license? Even cops did not have the license to kill anybody they wanted to.

Movies are about watching them and yearning for them, either for their past or what the audience hopes will come, mostly both. In this way, actors are like priests and priestesses: the embodiment of paper and fancy, that which sorts out the overwhelming present into a useable past and a prophecy of the future we think we desire.

But what was most riveting was the actor who played this character. In the ad, he wears a tuxedo, leaning forward, his elbows against one raised thigh, as if his bent leg were propped up in a chair, in one hand a cigarette, in the other a gun with a silencer. His face was different, new, cruel, impossibly handsome, confident, sophisticated, smart, tough. This was what I thought was my introduction to Sean Connery, whose first name I could not pronounce because I had never seen it before. My mother was not familiar with it either. I did not know any Black or Italian kid in the neighborhood with that name. Finally, watching the resident movie critic, Judith Crist, on the Today show one morning review a movie he was in, I learned how to say his name. I thought to myself at the time “Oh, I would not have thought of saying it like that.”

I had actually seen Connery in Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure (1959) a few years earlier with my older sisters, where he played a villain. He made no impression on me at all. None of us children at Saturday matinees knew anything about character actors and who played villains. Only the actors who played the leads mattered. Gordon Scott, who played Tarzan, was the only actor who mattered to me. The rest were there to give Tarzan a reason for being. And in our childish thinking, the lead had to be a better actor than the other people in the cast. In any case, I would not have recognized Connery anyway, even if I had been more attentive to supporting actors. As Bond, he seemed a completely different looking person. I had seen him in a Disney film called Darby O’Gill and the Little People. (My mother thought sending me and my sisters to see Disney movies was completely safe and wholesome.) I did not think that that actor was James Bond. As a child, a role made an actor real, not the other way around.

Connery was now, in 1962, the coolest actor ever. I thought Dr. No was the greatest movie I had ever seen, mostly because of Connery, his magnetism, his sex appeal. (Even at the age of ten, I did not like it when Bond told his Black Jamaican sidekick, Quarrel, to “fetch my shoes.”) My mother liked him too because he had the macho flair of her favorite actors, Clark Gable, Brian Donlevy, Rory Calhoun, James Arness, and Robert Mitchum. (My mother never liked the king of macho actors, John Wayne.) Connery’s exiting the casino at the beginning of the film while putting his winnings in his jacket pocket or walking across the hotel lobby in Jamaica about a third of the way through was as thrilling as watching him fight or speak.

I knew those actors my mother liked and had seen them in movies or on television. But they had begun acting in movies before I was born, so I did not consider them actors for me, for my generation. Actors like Elvis Presley, James Garner, Paul Newman, Steve Reeves (no accounting for childhood taste), and especially Sean Connery were my actors because they became famous after I was born. Connery was the first actor whose monumental fame unfolded during my development as a moviegoer and a fan. He was more famous, by far, than any other actor in the 1960s. He was advertised more than any other actor.

His face was different, new, cruel, impossibly handsome, confident, sophisticated, smart, tough. This was what I thought was my introduction to Sean Connery, whose first name I could not pronounce because I had never seen it before.

When the second Bond movie, From Russia with Love, was released the following year, I vibrated with such anticipation about seeing it that a few times a week I would walk by the downtown theater where it was playing—I think it was the Trans-Lux, about eighteen blocks from my home—just to stare at the stills and the paneled poster that announced: “James Bond is Back!” I could not separate the actor from the role, and the producers—Harry Saltzman and Cubby Broccoli—wanted just that effect. Perhaps all movie producers do with a movie series they hope will be, what is called today, a tentpole. They rarely get it but with Connery they did. That success was what made Connery want to be free of the role. But it made me want to see any movie in which he was cast.

I was never more fascinated with an actor in my young life. I read the gossip columns of Dorothy Kilgallen and Earl Wilson for any mention of Connery. I learned that he wore toupees and that his marriage to an actress named Diane Cilento (whom I would see in a 1967, Martin Ritt film called Hombre when I was in high school) was in trouble and this was disappointing. (Of course, to be disappointed that an actor wears hairpieces is rather like being upset that he wears makeup and a costume but I was just a boy who believed in movies as if they were a sort of spectral evidence.) I learned he had signed a five-picture deal to play Bond and he wanted out, desperate to play anything else for fear of being typecast by the role. My mother warned me about the terrors of typecasting: “Look what happened to Johnny Weissmuller,” she said. “Gee Whiz,” I thought, “I like Johnny Weissmuller, but he is nothing compared to Sean Connery.” Besides, playing James Bond was far more impressive than playing Tarzan or Jungle Jim. But it was my fervent hope that he was bigger than Bond.

I was never more fascinated with an actor in my young life. I read the gossip columns of Dorothy Kilgallen and Earl Wilson for any mention of Connery. I learned that he wore toupees and that his marriage to an actress named Diane Cilento (whom I would see in a 1967, Martin Ritt film called Hombre when I was in high school) was in trouble and this was disappointing. (Of course, to be disappointed that an actor wears hairpieces is rather like being upset that he wears makeup and a costume but I was just a boy who believed in movies as if they were a sort of spectral evidence.) I learned he had signed a five-picture deal to play Bond and he wanted out, desperate to play anything else for fear of being typecast by the role. My mother warned me about the terrors of typecasting: “Look what happened to Johnny Weissmuller,” she said. “Gee Whiz,” I thought, “I like Johnny Weissmuller, but he is nothing compared to Sean Connery.” Besides, playing James Bond was far more impressive than playing Tarzan or Jungle Jim. But it was my fervent hope that he was bigger than Bond.

I saw the other movies he appeared in at the time he was playing Bond: Hitchcock’s Marnie, Basil Dearden’s Woman of Straw, Sidney Lumet’s The Hill, and Irvin Kershner’s A Fine Madness. I did not see them in their first runs but, growing up, it was not very hard to see a movie in the theater after its initial run. They would return as second features on a double bill, as re-releases because the studio did not think the film really reached its audience the first time out, or as a feature at the one-dollar, 24-hour movie houses, which were popular in my youth. James Bond movies, for instance, were constantly being re-released as double features with the tagline, “James Bond is Back-to-Back.”

I cannot say that I liked any of Connery’s non-Bond movies when I saw them as a boy. I did not understand Marnie or A Fine Madness at all. In the latter, he played a character I found irritating. I cannot say I liked The Hill when I first saw it, but it impressed me and Connery’s character was complex, something deeper than Bond. But, on the other hand, he was not Bond and I was still attracted to, not enchanted with anymore, the Bond movies when The Hill came out. Ossie Davis, the great Black actor and playwright, was also in the film and that made it special for me, as any film with a Black person in it was special to me at the time. Woman of Straw was not much of anything. Connery, playing a scoundrel, was a physical presence, as he looked exactly as he did in From Russia with Love, but the film made no impression on me, probably because I did not like the female lead, Gina Lollobrigida, and would have preferred Sophia Loren or Shirley MacLaine, who were my favorite actresses at the time. I was always pairing up my favorite actors in imaginary movies.

In a few years, I outgrew the Bond movies. It was surprising how quickly it happened. At this point, in high school, I was around people who went to art house theaters and called movies “films” and talked about directors. (I was still at the stage where I had no idea who made movies and did not care.) They told me that what movies, excuse me, films, were really about was far beyond my poor literal viewing of what appeared to be the narrative. All I knew was that whatever Bond films really were had no more interest to me than what they seemed to be. I understood movies well enough to know when I did not need a particular type anymore. I craved a different experience in movies.

But Connery continued to interest me which is why I saw Thunderball and You Only Live Twice, even though neither film really did much for me. Connery himself was changing physically, as a presence; he was getting, as Dorothy Kilgallen put it, “long in the tooth.” He was excessively pampered, indulging the sensual living of the sort that a rich actor could indulge in. This, coupled with the boredom and contempt he now plainly showed in playing Bond, made me think of what someone told me Ernest Hemingway said about Spencer Tracy: just another rich, dumb, fat actor, or words to that effect. I saw every Connery Bond film in the theater during the time of its original release including his return to the Eon franchise in Diamonds Are Forever in 1971 and Never Say Never Again in 1983, a non-Eon Production that was a remake of Thunderball, a Bond film that always felt bloated and ponderous to me. I saw Diamonds Are Forever the week after I saw Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry and found the Bond film dull and irrelevant in comparison.

In a few years, I outgrew the Bond movies. It was surprising how quickly it happened. At this point, in high school, I was around people who went to art house theaters and called movies “films” and talked about directors. … They told me that what movies, excuse me, films, were really about was far beyond my poor literal viewing of what appeared to be the narrative. All I knew was that whatever Bond films really were had no more interest to me than what they seemed to be. I understood movies well enough to know when I did not need a particular type anymore.

Never Say Never Again is the sort of film that only an aging romantic male lead could get away with: playing a role you have aged out of and ought to be embarrassed doing. He did Bond as a young actor as action comedies; now, in his final bow, he was doing Bond as a farce. Bond had ceased to be sexy and was simply lecherous. But Bond movies still made money with Connery playing the role, as Never Say Never Again did. They were for Connery what the Rocky movies were for Sylvester Stallone, a sure-fire trip to the bank with a large check. This sort of “dirty old man” casting would get even worse for Connery, or the viewer, with Entrapment (1999), playing the love interest of a far younger Catherine Zeta-Jones. Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Humphrey Bogart, and John Wayne did that sort of thing too. When Joan Crawford was doing this in her 1950s movies, she was simply a lonely predator, the faded Queen Bee. I suppose things have improved for actresses since those days.

I thought Never Say Never Again was fun, and quaint, in its way. By that time, I had seen Connery in Robin and Marian (1976), The Wind and the Lion (1975), and The Man Who Would Be King (1975), all date movies with my then-girlfriend Ida, and we both liked them very much, indeed, were much moved by them. Connery seemed mature now, not just a sex piece, not just a box of a few tricks as he was playing Bond. Ida never liked Connery as Bond and thought he aged into a better and more interesting actor. When I took my daughters to see Connery in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), they could not believe that the actor playing Indiana Jones’s father had been James Bond. “That old man!” my youngest daughter sneered. Together, she and I watched From Russia With Love a few weeks later. Her response: “I liked him better as Indiana Jones’s father. Those old Bond movies are really dated. You really like that stuff when you were a boy? Wow! He was really good looking, though.”

He did Bond as a young actor as action comedies; now, in his final bow, he was doing Bond as a farce. Bond had ceased to be sexy and was simply lecherous. But Bond movies still made money with Connery playing the role, as Never Say Never Again did.

I took my family to see Connery’s last movie, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003). (It was my idea to see the movie. My family would never have gone otherwise.) I did not like it much, as it failed to live up to the comic book, excuse me, graphic novel series of Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill. My wife and daughters absolutely hated it and would have walked out had I not insisted I wanted to see it through. It was bad in the way these sorts of big, special effects movies are, lumbering, poorly scripted, making the viewer fight paralyzing indifference all the way through. Connery himself claimed not to have understood the movie or his part or something like that. This seemed a lame response from a tired and embarrassed actor who had been disappointed by bad reviews and mediocre box office returns. I was glad to have seen it in the theater and especially so as Connery would not appear in another movie. There is something touching about this movie for me, the death of Connery’s character, Allan Quatermain, the brief evocation of Africa. I liked Connery around Black people. Perhaps his Scottish ethnocentrism made him seem more genuine around them. I think of my mother taking me to see the re-release of the 1950 version of King Solomon’s Mines with Stewart Granger as Allan Quatermain. It was the only movie about Africa that my mother ever liked because of the seeming authenticity of the Africans who were cast. (The footage with the Africans is long and not, God be praised, taken from Trader Horn.) Twenty years earlier, Connery could have played a compelling Quatermain in a remake of King Solomon’s Mines without the comic book superhero nonsense. I would have liked that because Rider Haggard’s novel was one of my favorites as a boy; he was right when he said he could write a better boy’s book than Stevenson’s Treasure Island. I did not know how true his Africans were but they were the first heroic Africans I ever encountered as a boy in a book or anywhere else. But Connery was not to be Quatermain in a good movie. It is always sad when an actor misses his chance with a character, sadder still for the actor’s audience.

I took my family to see Connery’s last movie, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003). (It was my idea to see the movie. My family would never have gone otherwise.) I did not like it much, as it failed to live up to the comic book, excuse me, graphic novel series of Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill. My wife and daughters absolutely hated it and would have walked out had I not insisted I wanted to see it through. It was bad in the way these sorts of big, special effects movies are, lumbering, poorly scripted, making the viewer fight paralyzing indifference all the way through. Connery himself claimed not to have understood the movie or his part or something like that. This seemed a lame response from a tired and embarrassed actor who had been disappointed by bad reviews and mediocre box office returns. I was glad to have seen it in the theater and especially so as Connery would not appear in another movie. There is something touching about this movie for me, the death of Connery’s character, Allan Quatermain, the brief evocation of Africa. I liked Connery around Black people. Perhaps his Scottish ethnocentrism made him seem more genuine around them. I think of my mother taking me to see the re-release of the 1950 version of King Solomon’s Mines with Stewart Granger as Allan Quatermain. It was the only movie about Africa that my mother ever liked because of the seeming authenticity of the Africans who were cast. (The footage with the Africans is long and not, God be praised, taken from Trader Horn.) Twenty years earlier, Connery could have played a compelling Quatermain in a remake of King Solomon’s Mines without the comic book superhero nonsense. I would have liked that because Rider Haggard’s novel was one of my favorites as a boy; he was right when he said he could write a better boy’s book than Stevenson’s Treasure Island. I did not know how true his Africans were but they were the first heroic Africans I ever encountered as a boy in a book or anywhere else. But Connery was not to be Quatermain in a good movie. It is always sad when an actor misses his chance with a character, sadder still for the actor’s audience.

Every time The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comes on television, I watch it, sometimes all the way through, sometimes only for a few scenes with Connery. It may alarm some people, and dismay others, that I have watched this admittedly wretched movie more times than I have ever viewed a masterpiece like, say, Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. Movies are funny that way in what they mean to a particular viewer, in what a particular actor means. Connery had achieved his fame as the definitive film version of a pulp adventure hero in a film series that became not simply successful but mythical and went out of his profession portraying a decent version of another pulp adventure hero in a vastly inferior film. His presence is the only reason the film will not ever be completely forgotten. It happens that way with actors. It happens that way with their fans too. Connery was the marker of my boyhood and its end, my growth, such as it was and as I had hoped it would be. You do not forget people who mark your life like that as, after all, we all must grasp for meaning wherever we can find it.