Why is there no museum to honor musician Chuck Berry?

“If you tried to give rock and roll another name, you might call it ‘Chuck Berry,’” said John Lennon, who once played onstage with him, like an adoring apprentice.

“The Shakespeare of rock ‘n’ roll,” Bob Dylan said.

“He’s the primary architect of rock ‘n’ roll music,” Kevin Strait, Museum Curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), told Smithsonian Magazine.

Historian Douglas Brinkley, who wrote the liner notes for Berry’s final album, called Berry “the indisputable father of rock & roll” and said, “Chuck Berry has won so many awards that someday it will take a tractor-trailer to move all his plaques to a museum.”

Though Berry was born in The Ville, the historically black neighborhood once home to a flourishing African-American middle- and upper-middle class, he was able to buy the Whittier house, a few blocks north, in The Greater Ville, only because the Supreme Court ruled in 1948 (Shelley v. Kraemer) that enforcement of racially-restrictive housing covenants in state courts violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Berry was in the first group of inductees to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame; received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grammys; was a Kennedy Center honoree; and played for two presidents. Rolling Stone ranks him fifth in their 100 Greatest Artists of All Time. NASA sent his work to represent us in interstellar space.

Chuck Berry, who died at 90 in 2017, was a lifelong resident of St. Louis. The city is a logical place to honor his legacy. But rumored plans for making one of his former houses a museum fell through. Why?

Manufacturing pride and solidarity

I have heard locals say St. Louis is not good about honoring its famous sons and daughters, from T.S. Eliot to Josephine Baker. Heidi Aronson Kolk, Assistant Professor, Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, agrees.

“St. Louisans have not been deeply committed to saving sites and histories associated with such celebrated figures,” she tells me by email. She names other musicians with local ties, including Tina and Ike Turner (“their East St. Louis house is privately owned but I would call it endangered heritage … most of the nearby club district/music-industry-related sites have been lost to decay/collapse”); Miles Davis (“whose East St. Louis residence survives and has been stabilized but is endangered due to financial issues”); and Scott Joplin (“whose Northside house was saved [but] is chronically underfunded”).

“And then of course there is Chuck Berry,” Kolk says.

Kevin Strait, Curator at NMAAHC, managed to get one of Berry’s Cadillacs, a blood-red Eldorado, and his guitar, Maybellene, for the Musical Crossroads exhibit, but it almost did not happen. I asked Strait about a house museum for Berry in St. Louis, and he said, “I would like to see it. We celebrate him a lot and he has a big presence inside our museum.”

Kolk says that in the Depression a group in St. Louis called the William Clark Society was involved in saving several 19th-century properties, including the Eugene Field House. Kolk’s book, Taking Possession: The Politics of Memory in a St. Louis Town House, is about one of those properties and “illuminates the processes by which civic pride and cultural solidarity have been manufactured in a fragmented and turbulent city….”

In any case, as the site administrator of the Scott Joplin House told local news, if a historically-significant building is to be saved, someone has to make it their mission. “You still have to have that person that’s the cheerleader for the project,” Almetta Jordan said. “Without that cheerleader, this building wouldn’t have been here.”

The William Clark Society is long defunct. Kolk says the closest thing to it is the Landmarks Association of St. Louis, Inc., a nonprofit with 1,300 civic, corporate, and family members. Landmarks’ Executive Director, Andrew Weil, stresses it is “the primary advocate for the region’s built environment,” which has “fought an uphill battle for 60 years to protect St. Louis’ historic architecture.” Weil explained to me that Landmarks does not usually buy properties, and “doesn’t approach preservation in terms of ‘celebrity’ properties. To do so would be irresponsible. We prioritize the cultural heritage of St. Louis regardless of whether there is a famous name associated with it.” But, Weil adds, Landmarks “recognized the significance of the Chuck Berry House when nobody else was paying attention.”

Kolk also mentions “enthusiast-collectors,” such as the Busch family, who fund private ventures often “tied to larger institutional projects.” (The Ulysses S. Grant cabin called “Hardscrabble” is on the portion of Grant’s Farm owned and operated as an animal park and petting zoo by the corporate parent of Anheuser-Busch.)

In any case, as the site administrator of the Scott Joplin House told local news, if a historically-significant building is to be saved, someone has to make it their mission. “You still have to have that person that’s the cheerleader for the project,” Almetta Jordan said. “Without that cheerleader, this building wouldn’t have been here.”

Museums for equivalent figures

The Ray Charles Memorial Library opened in Los Angeles in 2010 and was renovated in 2017 with presidential libraries in mind. Charles had the building built in 1964 and used it for his offices, recording studio, and archives. The Library is run by a nonprofit that Charles himself started in 1986, nearly 20 years before his death, with a $50 million endowment, and to which he left his estate. Curators “hope the exhibits will open up a world of possibilities to youngsters after they see how the soul icon transcended socioeconomic, musical and racial boundaries during a career spanning more than 50 years.” It also offers grants.

The BB King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center, in Indianola, Mississippi, opened in 2008. It is a stately place—one of the buildings is a former cotton gin where King used to work—with exhibits on not just King but also the Blues Trail. It offers outreach programs. While King did not endow the nonprofit foundation that runs it (that money came from “concerned citizens,” an administrator tells me), he was “very involved” and gave the museum permission to use his name in perpetuity, as well as a variety of artifacts. He is buried on the grounds.

Chuck Berry seems not to have made similar moves in his lifetime to ensure, say, a museum dedicated to his legacy and to African-American music shaped by St. Louis, a city often seen as an intersection of various cultures in the heart of the country. (Berry himself thought part of his appeal to white audiences was his combining R&B and country-and-western.)

What might be

And so some hoped, in a vaporous way, a house museum might be the answer. A 2014 article in Riverfront Times listed houses Berry lived in, and when one of them, a five-bedroom place he bought after he became prosperous, came up for sale, they enthused:

“Not only is this house gorgeous and charming, but it used to be owned by St. Louis’ very own rock & roll daddy, Chuck Berry. That’s right, the man who invented rock & roll once lived in this Visitation Park stunner [on Windemere Place]. Berry bought it in 1958, the same year that ‘Johnny B. Goode’ and ‘Sweet Little Sixteen’ took over the charts, and owned it for close to two decades. […] And though it’s currently zoned for residential use, it’s easy to imagine this place serving as the future site for a Chuck Berry museum.”

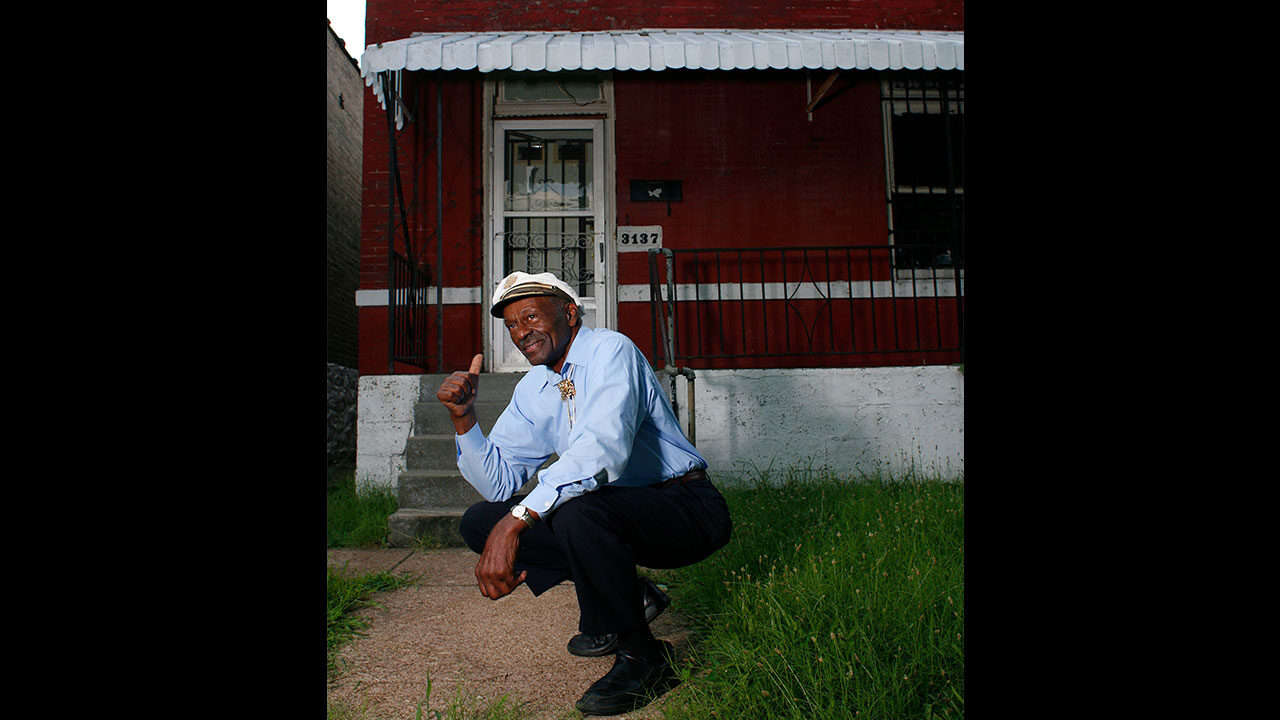

But there never seems to have been a plan. Rumors of one came after the St. Louis Development Corporation (SLDC), “the economic development arm for the City of St. Louis,” issued a Request for Proposal (RFP), in 2017, for Berry’s former house at 3137 Whittier, in the historic neighborhood called The Greater Ville, which he owned as he was coming up. Some media interpreted this as action.

Billboard magazine announced, “St. Louis is planning to convert Chuck Berry’s one-time home into a museum and to create a cultural district around it honoring the rock ‘n’ roll legend and other prominent African Americans who have lived in that part of the city.”

Dale Ruthsatz, Deputy Executive Director at SLDC, explained to me that the Land Reutilization Authority (LRA), the city’s land bank, owned then (and still owns) what everyone refers to as “The Chuck Berry House” on Whittier. LRA ends up owning many tax-delinquent properties, all over the city, he said, which are auctioned for cheap on the courthouse steps.

(There are 25,000 vacant properties in St. Louis, says the Post-Dispatch. Nearly half may be owned by the LRA.)

I asked if the Zillow estimate for Berry’s little house, $15,000, was at all accurate. Ruthsatz said LRA property prices are assigned by neighborhood, and the house on Whittier is in one of the poorest areas of the city. “I doubt it’s 15k,” he said gently.

Ruthsatz could not tell me who wrote the RFP, only that that person was no longer employed at SLDC. This person included a section that suggested a developer might make the house a cultural site by returning it to its “original and historic condition,” building another museum about Berry next door or nearby, and creating a plaza for musical and other events. In return they might receive state and federal tax credits (including New Markets Tax Credits, meant to encourage investment in low-income communities), a 25-year tax abatement, and information on possible financing options.

“It didn’t ever come to pass,” Ruthsatz said. “We would all like to [have it happen], but it isn’t going anywhere at this point.”

I asked if the Zillow estimate for Berry’s little house, $15,000, was at all accurate. Ruthsatz said LRA property prices are assigned by neighborhood, and the house on Whittier is in one of the poorest areas of the city.

“I doubt it’s 15k,” he said gently.

In reality, a source suggested to me later, it might be had for as little as $1,000 or even one dollar.

The real contender

The 1,000-square foot house at 3137 Whittier seems a good choice for one kind of commemoration of Chuck Berry. It was built in 1910, for $2,200, a modest two-bed, one-bath house with a basement in a working-class neighborhood. Berry and his wife, Themetta “Toddy” Suggs, bought it in June 1950 and lived there until July 1958. Two of their four children were born during that period. Berry himself poured sidewalks and built a two-room, concrete-block addition in 1956 for music-making. A faded letter “B” for “Berry” is in the metal awning over the porch. After the family moved to Windemere Place, Berry rented the Whittier house, and his secretary, Francine, lived there. At some point, perhaps in the late Sixties, he sold it.

The nomination of the house for the National Historic Register was written by Landmarks Association, who recognized the property as significant and paid an employee to nominate it so that it would be protected by the city’s demolition ordinance and eligible for redevelopment tax credit incentives. The nomination was approved in 2008. It says it is “the one property most closely associated with the rise of Berry’s career, the development of his musical style and the time when his earliest string of hits had their greatest impact. […] While other Chuck Berry sites do exist, none has been associated with his career over such a relevant period of time as the house on Whittier.”

It was here Berry wrote “Maybellene,” “School Days,” “Rock and Roll Music,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “Brown Eyed Handsome Man,” “Too Much Monkey Business,” “Reelin’ and Rockin’,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” and many other canonical songs he continued to play for 60 years.

This was the “golden period” of Berry’s career, the nomination says, “during which he established his legacy as perhaps the single most important artist in the history of rock and roll” and became an influence on the very musicians who pushed him out of the limelight, such as The Beatles and Rolling Stones.

It was here Berry wrote “Maybellene,” “School Days,” “Rock and Roll Music,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “Brown Eyed Handsome Man,” “Too Much Monkey Business,” “Reelin’ and Rockin’,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” and many other canonical songs he continued to play for 60 years.

“Berry also was important as the first African-American artist to strongly appeal to both black and white audiences during a decade of civil rights turmoil and beyond,” the nomination says. In this vein, the house has additional national significance. Though Berry was born in The Ville, the historically black neighborhood once home to a flourishing African-American middle- and upper-middle class, he was able to buy the Whittier house, a few blocks north, in The Greater Ville, only because the Supreme Court ruled in 1948 (Shelley v. Kraemer) that enforcement of racially-restrictive housing covenants in state courts violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The problem with museums is agreement

If you had asked Chuck Berry at the turn of the millennium if a little shotgun house he owned in the ’50s was important to understanding his artistry, I suspect he would bristle, as he did when Robbie Robertson of The Band asked him about the decline in his productivity and popularity in the Sixties. Berry did not recognize it. His artistry was always today.

Similarly, Douglas Brinkley said the acquisition of Berry’s Cadillac by NMAAHC was “smart,” since in his allusions to cars “Berry had created an artistic commentary on American life, its fluidity, its mobility and the restlessness beneath the surface.

“But, in the end,” Brinkley said, “that red Cadillac Eldorado is just a trinket or an artifact.”

House museums are often drab and small, because they were drab and small when cultural figures lived in them. A friend told me he would visit a Chuck Berry house museum if it was filled with guitars. I said it was likely never filled with guitars when Berry was starting out, and it was important that the music came despite (or due to?) a lack of things. Besides, if you crammed a house museum with inauthentic things, special lighting, sound effects, and interpretive signs, you would endanger the very context you hoped to preserve.

If you had asked Chuck Berry at the turn of the millennium if a little shotgun house he owned in the ’50s was important to understanding his artistry, I suspect he would bristle, as he did when Robbie Robertson of The Band asked him about the decline in his productivity and popularity in the Sixties. Berry did not recognize it. His artistry was always today.

The “frozen in time” museums you see across the country, many of them just private collections made public, are often amateurish, even schlocky, but that can be as important to their authenticity as a poorly-proofread menu is to an eatery. One Jerry Lee Lewis Museum in Ferriday, Louisiana, is just a collection of family memorabilia, including The Killer’s potty-training chair, which is signed.

Not everyone cares. On a blog post about Josephine Baker’s disappearance from St. Louis’ cultural landscape, one commenter said:

“Bigger picture is the whole question of why we would want to ‘save’ most people’s childhood homes or birthplaces, at all? Yes, it was an old structure, and yes, it had ‘history’, but why make it a museum? [D]o we care where Steve Jobs or Bill Gates were born or spent their childhoods? […] Madonna or Jon Bon Jovi? The importance of all these people is in what they’ve done, not in which house they were born. Their history will live on in books and, now, electronic media, …in the Smithsonian and at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. [S]hould we be saving Chuck Berry’s local childhood home? Stan Musial’s? That stooge of Three Stooges fame? […] Life moves on–we can’t save everything….”

New trends in curation say museums “are no longer only spaces that house stagnant cabinets of curiosity.” They say excitement is necessary to a museum’s financial survival, or that young people in particular need technologies to engage with the past.

Reflecting on relevance and the shared needs of a community is useful. But what I have gotten from visiting the homes of Lincoln, Chekhov, Twain, Hemingway, and others, is the context of quiet domesticity, even deprivation, compared to comforts we have now. In the Kremlin Armory, I was not as interested in shiny, bejeweled things as I was in Peter the Great’s boots, Catherine the Great’s ink pen, or the way a coach’s carriage box was held off its chassis by wide leather straps serving as an early suspension.

What we allow to remain, we will fill with what meaning we can summon. But there will always be grieving over what was not saved.

Joe Edwards helped revitalize St. Louis’ Delmar Loop and founded the nonprofit St. Louis Walk of Fame. He was friends with, and a professional associate of, Chuck Berry for decades. Berry played 209 times in Edwards’ restaurant and venue Blueberry Hill, on the Loop. Edwards told me that when the RFP was announced, he tried to get investors together to buy the house.

What we allow to remain, we will fill with what meaning we can summon. But there will always be grieving over what was not saved.

“I got bids, but people just…it didn’t happen,” he said. “It’s so far out of the way now, I’m not sure anyone would get to it.”

Edwards said he had an interest in a museum—he has been a tireless promoter of Berry’s legacy—but that it might be “marvelous” and “sensible” in the Central Corridor instead, the booming area from the Gateway Arch to Washington University. Another site, he said, might be on Delmar Loop, near Blueberry Hill and the statue of Berry erected in 2011, for which Edwards helped fundraise $100,000.

Who pays?

Mark Walhimer, Museum Planner, Museum Planning LLC, told me he often gets calls about making museums from houses.

“But historic houses are having a rough time,” he said. “Numbers of visitors are decreasing, and it gets more and more difficult, especially with younger audiences. How do you stay relevant; how do you create an experience? When it works, it’s often part of a larger museum.” Admissions alone will not pay. He mentioned Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, which he said survives because it is maintained as part of a properties collection.

“It’s a tough go,” he repeated. Getting a house museum going often takes three to seven years, and there are the costs of starting such a museum, opening, running and maintaining it, as well as special projects. “It is seldom successful,” he said. “Not to say that it’s not valuable, or not of historic significance.”

“When I have seen a project work well, it is part of an urban redevelopment plan, a partnership between local businesses, city support and planning, and the private nonprofit; without the larger plan and the public/private partnership it is very difficult.”

The “frozen in time” museums you see across the country, many of them just private collections made public, are often amateurish, even schlocky, but that can be as important to their authenticity as a poorly-proofread menu is to an eatery. One Jerry Lee Lewis Museum in Ferriday, Louisiana, is just a collection of family memorabilia, including The Killer’s potty-training chair, which is signed.

According to the federal government, “the four main categories of museum funding are private donations [38 percent], earned revenue [28 percent, including event rentals, food sales, plastic dinosaurs, and admissions, only 5 percent of the total], government grants [24 percent], and investment income [less than 12 percent].”

Locally, charitable donation has changed. More St. Louis nonprofits are vying for the same amount of possible funds ($1.8 billion in 2016) from fewer donors, who are predominantly wealthy.

So why is this complicated?

Two billion dollars is a lot. Surely there are benefactors for such a project. I talked to or contacted more than a dozen knowledgeable government, nonprofit, and private sources, but no one had a solution, and some did not respond.

I spoke with Lindsey Derrington, who wrote the winning National Historic Register nomination for The Chuck Berry House. Derrington is now Executive Director of Preservation Austin (TX), but in 2008 she was working for Landmarks Association of St. Louis. She told me that researching and drafting the nomination was part of her job, but she invested herself in it as a “passion project” that she worked on at all hours. The goal was to bring attention to the fact that the house existed, since there was no other literature on it.

“This is it for us in St. Louis,” she remembers thinking.

A National Register listing meant the chance of redevelopment was greater, in part because it would help with federal tax credits. Derrington said she would have bought the house herself, but she was only 23 and her income did not allow it.

The RFP was issued after she moved from the city, and she does not know why the museum never happened. But she is clear that she would rather the sentiment not be, “a museum or nothing.”

“A museum would be amazing,” she said, “but if there’s no funding or appetite, what’s the next step?”

Derrington’s former coworker, Andrew Weil, now Executive Director of Landmarks Association of St. Louis, agreed. Stabilizing the building is not enough, he told me; someone has to be living in it. “Vacant buildings in north St. Louis have a really bad propensity for disappearing overnight,” he said. “It’s kind of a miracle it’s survived this long in its current condition.”

He also explained hurdles to making it a museum. If a nonprofit foundation wanted to do so, it would need a for-profit arm to get tax credits. “That’s not impossible,” he said, “but it requires some, shall we say, legal gymnastics to do something like that. And the old RFP, which said the property could be used for cultural purposes, or as a community center with a music emphasis, is no longer active.”

When the RFP received no response, Weil met with City Planner Don Roe and Cultural Resources Office Director Dan Krasnoff, who worked together to nominate the house to the National Trust’s “America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places” list. It didn’t make the cut, and Weil was surprised.

Landmarks Association is 61 years old. Weil said that in the ’70s they did own some properties and rehab them, mostly for demonstration’s sake, and they have been doing a rehab of their own offices. Otherwise they do not buy properties. He hopes someone will buy The Chuck Berry House and save it. Like many I spoke to, he invoked benefactors and angels.

What is at stake

Lindsey Derrington said she wished St. Louis would take over not just the house but the greater project, “taking some pride in the incredibly important figures in midcentury American history in a ward known for depopulation and disinvestment.”

She means the Fourth Ward, part of north St. Louis, now one of the most impoverished and crime-ridden areas of the city, though The Ville and the area around it used to be the home of the African-American financial and artistic elite. Redlining and other racist policies destroyed this middle class, and now no one knows how to fix the problems.

Sam Moore is Fourth Ward Alderman. Google his name and you will find videos he has made to bring attention to his Ward’s “devastation.” In one he stands before a collapsing multistory house. They call these “dollhouses,” as the back walls are missing, giving a view of everything inside. The once-elegant structures are victims of brick theft—the stealing of valuable bricks sold for use elsewhere in the country.

“3137 Whittier. This is a sin. This is a whole travesty here,” Sam Moore said as he walked over chunks of plaster and holes in the floor.

“Don’t take ’em long,” Moore says. “Once they get wind your house is empty, they get started on it.” He says brick theft “brings all the other crimes,” including arson, said to make it easier to harvest the bricks. The New York Times reported that St. Louis brick is so distinctive and desirable that eight tractor-trailer loads leave the city for places such as New Orleans and Texas every week.

Moore took a news crew through the (brick) Chuck Berry House in 2017. He said there were more than 1800 empty buildings like this one in his ward alone, and he had already torn down 600.

“3137 Whittier. This is a sin. This is a whole travesty here,” he said as he walked over chunks of plaster and holes in the floor. The report described the house as “crumbling” and its condition “deplorable.”

“We should be proud of this place but we’re not,” Moore said. “Most people in the ward don’t even know it’s here.”

An answer

Looking into this, I found mostly confusion—over rumors that someone planned to make a museum; about why that never happened; about what the future held. Finally, I spoke with a person at the top of the redevelopment/preservation field in St. Louis, who asked to remain anonymous. I think they became impatient with my naiveté and just said it: The reason there is no plan for The Chuck Berry House is its particular location in the Fourth Ward.

“The neighborhood is seriously distressed and rough,” they said. “The neighborhood is disappearing around it. There are drug deals on porches in broad daylight. You couldn’t be teaching kids about music as a kind of hope, in some community center, while that was going on nearby. Unfortunately, the idea is kind of absurdist.”

I asked if eventually, maybe after the Berry House was gone, the emissaries of gentrification would swoop in, since the neighborhood is close to the revitalized Corridor.

The source said, “There are already half-a-million people missing from the north side, and the typical, easy form of gentrification doesn’t happen here. More often, the long-term problem of the erosion of the physical fabric of the community [continues and] is not replaced with anything in a reliable or timely fashion.

“It is a completely broken real-estate market. There are no comps; you can’t get loans; the amount of money to rehab a building is ten times what you could sell it for, if there was a market for the building.”

They mentioned Paul McKee, Jr., a white developer in St. Louis often seen as an alleged profiteer on the misery of black residents. His move to buy properties and hold them for speculation is also blamed for vacancies, which causes more crime, including brick theft. My source was more tactful and said McKee is “somebody who can afford to wait for a rise in value, where others cannot.” Anyone who bought The Chuck Berry House would need similar resources, they implied.

“The LRA is the largest property owner in St. Louis,” they said, “but many of their properties will not sell, even if they cost a dollar. People won’t buy because of economics and the dangerous neighborhood.”

The Chuck Berry House would need “someone who is crazy, not with deep pockets particularly, but a benefactor.

“I really care about this property and recognize its significance,” they said, “and someone is going to need to put money into preserving it until the neighborhood improves. So far no one has stepped forward to do that.

“It’s on the radar of the city and is kind of a priority for board-up and security. But the number of building inspectors is nowhere what we need, and their budget and manpower is quite frankly a joke. They can’t keep up. I believe it’s a really important building, but it needs a purpose.”

Asking about The Chuck Berry House turned out to be like asking why poverty exists. The confusion lies between a too-easy answer and an impossibly complicated one.