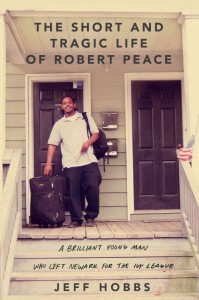

The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace: A Brillliant Young Man Who Left Newark for the Ivy League

“If you wanna go and take a ride wit me / We three-wheelin’ in the fo’ with the gold D’s / Oh why do I live this way?”

Music flows through Jeff Hobbs’s The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace. Though Nelly’s song “Ride Wit Me” is mentioned as the soundtrack to one particularly boisterous college party, these lyrics inform Hobbs’s approach to his subject—a portrait of his Yale roommate Robert DeShaun Peace. Through interviews with Peace’s friends and family, Hobbs attempts to understand how Peace, whose Yale undergraduate degree in biology seemed to have him poised for success, could end up being murdered by rival drug dealers. Hobbs is intent on figuring out “Oh why [did Robert] live this way?” Though we hear how Peace lived and died, we do not ever get an answer to this question.

Indeed, Peace is an elusive subject. After graduating from Yale, every decision that he makes is met with incredulity. His friends and family do not understand why he wants to go to Rio, why he wants to teach at his former high school, why be became an airline baggage handler, and why he persisted in selling drugs. Recounted conversations from this time in his life show a subject in relief, in the questions that Peace’s family and friends ask we see paths not taken and justifications for their own lives. His Yale friends—Oswaldo and Raquel, Puerto Rican students from Newark and Miami respectively—have trajectories that offer strange echoes to Peace’s. Both come from poverty, struggle to fit in at Yale, and afterwards experience difficulty figuring out what to do with themselves. Oswaldo languishes in Newark after graduation for several years until he is pushed to a psychological breaking point, seeks career counseling from Yale, and finally realizes his dreams of going to medical school. He keeps in touch with Rob (what Peace’s Yale friends call him), but admonishes him for not pursuing his dreams of graduate school and leaving Newark permanently. Raquel has a career and a stable boyfriend, but spends much of immediate post-graduation time partying and existentially adrift until she becomes pregnant at 25, has a son, and gets married. The narrative here is that these consistent loving presences allowed her to achieve conventional success and emotional maturity. His Newark friends—the Burger Boyz—who attended prep school together and remained close describe Shawn (as Peace is known in Newark) as a leader despite the fact that he is mired in the same difficulties and not outwardly more successful. They balance jobs, families, and Newark. Three out of four of them never finish college and struggle to get by, making them easily seduced by the plan that will lead to Shawn’s murder—selling a vast quantity of drugs to make some quick money so that they can do more with their lives. They seem both scared of Shawn’s Yale pedigree and willing to trust their friend. His mother, Jackie, describes Shawn as lost, curious, and in search of something intangible. Even as she does not know about his drug dealing, she imagines that his Yale degree will lead him somewhere else. Her hope for her son is palpable; she wants him to do more with his life than she felt she had accomplished with hers, but she wants to see him not just achieve but to live.

Peace’s life is presented as a narrative with Yale at its pinnacle and everything that follows as downfall. Most of the book purports to be a portrait of a man unraveled. Most of what we see, however, is mediocrity not failure. His real estate ventures barely break even, he has a series of girlfriends with whom he always fights, and he is widely liked. He is loyal yet distant, hard working yet not upwardly mobile. It is this stasis that becomes the problem, but it is difficult to read this as failure or downfall because we do not know what ambitions or desires Peace harbored. In the space of this motivational vacuum, Hobbs centers family. Peace’s efforts to support his mother financially and the loss of his father are the two reasons given for his downfall. As a narrator, Hobbs is deeply invested in narratives of paternal loss (which we hear about as he describes his undergraduate course work). He dwells on Peace’s relationship with his father, Skeet, which had been happy until his father was erroneously sent to jail for murder when Peace was 7 years old. Though Skeet never gets the appeal that he desperately hoped for and dies in prison of brain cancer in 2006, the tangle of legal ineptitude and shoddy investigation that places him in prison haunt Peace, who maintained the relationship and visited his father regularly. Skeet’s proximity to the criminal element in Newark are presented as reasons for Peace’s easy integration into the neighborhood—schoolboy afternoons spent socializing with people gave him connections and his father’s drug dealing is presented as a sort of inherited character trait. While this parental drama is compelling, it presents Peace’s life as a struggle between his mother’s desire for racial uplift (which would echo her own parental narrative of hard work and homeownership) and his desire to fill the void left by his father. While we are invited to “take a ride” with Peace, there is much that falls out between Rob and Shawn. His wanderlust—he traveled to Rio, Korea, Croatia, and other locations, is remarkable and only touched upon. Though it may be impossible to know what happened on many of these travels, this urge does not fit into the standard dilemmas (mother vs father; Yale vs Newark) presented for our consumption. Yet they give a glimpse at some pragmatic if not existential answers to Peace’s choices; he wanted freedom and money to travel. We also hear about his plans to buy properties in other states (Ohio and Florida) and flip them—easy money and freedom. Yet his aspirations as a real estate mogul are only presented as thwarted and not as manifestations of some deeper desire. These sparks of individuality are sadly forever snuffed out and not accessible to us as readers.

The demon is not Rob or his ambitions or lack thereof. It is place and this is what multiculturalism cannot vanquish.

In lieu of hearing about Peace, then, the book becomes a meditation on structure and not just any structure, but the workings of multiculturalism in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Multiculturalism was the pervasive ideology of this time period, governed by the belief that race did not matter; people could come together and celebrate their differences and work together to form one cohesive whole. The melting pots of university, Yale in this case, are meant to be performing this ideological work. Students were supposed to live and work together, learn from each other’s differences and forge a more successful future. Peace’s life narrative with its unfocused dissolution into premature death might indeed be taken as an example of multiculturalism’s failure since Peace does not achieve conventional forms of success. As a mode of critique, then, the book points to the impossibility of the dream of multiculturalism yet it does not break away from a belief that it could work. In this way it is not surprising that the sections of the book that deal most directly with college are the most successful. This is when Hobbs and Peace lived together, partied together, and talked. Though Hobbs presents himself as opposite to Peace in many ways, they seem to get along seamlessly. In part this is because Hobbs fancies himself down with Peace and blackness, a belief that is drives the book and forms its central tension. Even as Hobbs writes that he has many black friends on the track team and listens to black music, he also focuses on the difficulties Peace faced trying to integrate into Yale society. He dwells on an incident where some white rowers refused to bus their trays angering Peace and leading him to stew about class privilege. In the vein he also describes Peace’s early jobs doing custodial work and distancing himself from the Yale community by having other friends spread throughout New Haven. On the side of multiculturalism, however, the book also bears witness to several moments where Rob is comfortable in this environment—he plays water polo, he joins a secret society. Hobbs argues that Rob is more integrated than he wants to admit. In these moments Hobbs voices liberal guilt and its accompanying desire for change.

But the demon is not Rob or his ambitions or lack thereof. It is place and this is what multiculturalism cannot vanquish. Dealing drugs in New Haven nets Rob a safety net of close to $100,000, which enables him to travel to Rio and he imagines take care of his mother while he figures out what else he wants to do. Instead, his uncle steals the money, which becomes the catalyst for more drug dealing, undesirable jobs, and ultimately costs him his life. Newark is what keeps him stuck. Despite Cory Booker’s initiatives to make the city safer, these do not help Rob. He is at its mercy in the subprime mortgage crisis and his choices are also shaped by September 11. Despite the overarching narratives of racial uplift via education, there is a suggestion that Peace’s narrative could be that of any other young person who came of age in this era when optimism and free-spirited partying without consequences gave way to recessions, terrorism, and a new era of anxiety.

Hobbs’s description of his contemporaries: “we were Americans in our midtwenties, finding apartments and homes, meeting our future spouses, picking (or sometimes falling into) our future careers” is what he describes happening to Peace albeit on different terms. Peace appears to be looking for relationships, finding a career (perhaps in real estate), and buying a home; yet these things do not bring him success. Instead, in death, Peace becomes a symbol of how one gets mired down in Newark with family, with drugs, with fewer employment opportunities. Structure and place apparently claim another individual, but since we didn’t get to know him well, we don’t even know what kind of fighting chance he may have had.