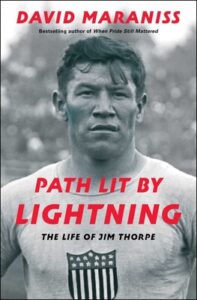

Authors approach the writing of sports biographies from a number of different perspectives. Almost by definition, a sports biography will be about somebody famous, somebody whose athletic feats have elevated a human being to the status of a modern-day mythic hero. On one end of the spectrum, a biographer might try to understand the process of myth-making, and draw conclusions from it by developing an argument, comparing and contrasting the life lived with the popular lives imagined. On the other end of this spectrum, a writer can back away from an expository format and construct a story, one without clear conclusions or arguments, but that nevertheless hooks a reader from start to finish with a clear and compelling arc and fascinating detours. Readers of A Path Lit by Lightening: The Life of Jim Thorpe clearly experience the latter from one of the most masterful storytellers within the field of nonfiction writing, David Maraniss.

An associate editor for The Washington Post, Maraniss is no stranger to writing books about larger-than-life topics. He has taken on the Red Scare and the fate of deindustrialized Detroit. He has written about the temperament of the United States during the Vietnam War; he has penned the biographies of two United States presidents, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama. And he has written about sports in ways that highlight the big stories and reflect the measure to which the world of athletics has become a central component of public life around the world over the past century and a half, including the 1960 Rome Olympics and the life and times of Roberto Clemente and Vince Lombardi, two of the most iconic sports figures of the late twentieth century.

With Jim Thorpe, Maraniss has once more written a book about a seemingly transcendent sports figure. Thorpe is widely recognized as one of, if not the, greatest athlete of the twentieth century. He won two gold medals in the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm; starred as a football player for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and, during the fledging first years of professional football, for the Canton Bulldogs; and enjoyed a long, if underrated, career as a professional baseball player, sometimes at the major league level. Yet for those who know anything about Thorpe’s life and athletic career, it also is one overshadowed by tragedy. Shortly after his Olympic triumphs in the pentathlon and decathlon, media reports surfaced that established Thorpe as having played minor league baseball professionally. A violation of the strict and uncompromising amateur rules limiting who could compete in the event, the International Olympic Committee, at the urging of the Amateur Athletic Union and the American Olympic Committee, stripped Thorpe of his trophies and gold medals in the pentathlon and decathlon. While never explicitly stated, the elitist White men who led America’s amateur sports did all they could to undermine the accomplishments of Thorpe, an Indigenous American and member of the Sac and Fox Nation.

Before addressing the narrative that Maraniss creates, I want to take a moment to note Jim Thorpe was a male sports hero. This probably seems like an obvious point to make since, until only very recently, social institutions have understood sports as a vehicle for demonstrating masculine heroism. In his biography, Maraniss leaves a discussion of gender largely unaddressed, something that I will return to briefly at the conclusion of this review. Yet he does place race and the United States’s conquest of Indigenous Americans at the center of his story. He weaves two narratives that highlight these issues throughout his account of Thorpe’s life.

While never explicitly stated, the elitist White men who led America’s amateur sports did all they could to undermine the accomplishments of Thorpe, an Indigenous American and member of the Sac and Fox Nation.

The first narrative is the story of Black Hawk, a Sauk war leader who would unite with the Fox nation in 1832 with whom he had famously led a rebellion of his people against their imprisonment on a reservation. In fact, Black Hawk actually brought together a variety of different Indigenous people who had once thought of one another as distinct, or even as enemies. Eventually, however, United States soldiers slaughtered a large number of Black Hawk’s band of resisters. They captured and imprisoned Black Hawk himself, who, in turn, almost immediately became a curiosity to White journalists and curiosity seekers. Among the first to capture Black Hawk’s image was the painter George Catlin who came to the rebel leader’s barracks in St. Louis. Maraniss writes, “He sought to idealize Black Hawk, not demonize him, portraying him as the classic noble warrior. And so was Black Hawk reimagined, an early representation of what would happen to leading American Indians many times through the decades of the nineteenth century in paintings and traveling shows and books, from Geronimo to Sitting Bull to Iron Tail to Crazy Horse and on to Jim Thorpe, some defanged, all romanticized, exaggerated yet diminished at the same time.”(13) Here, Maraniss, very early in his book, foreshadows a story of Thorpe as a masculine hero who will end up emasculated, comparable to warriors that the United States cavalry and the march of “civilization” defeated and controlled in the nineteenth century.

This connects to the second trope that Maraniss highlights in his biography of Thorpe, a simple phrase that White writers used to portray Indigenous Americans generally, and that dogged Thorpe throughout his public life: Lo, the poor Indian. British poet Alexander Pope originally coined these words in a 1734 poem, and while he had originally written them as part of a piece that romantically associated Indigenous Americans with the natural world, nineteenth-century writers used the phrase somewhat differently. To them, Lo, the poor Indian came to evoke the image of a defeated people tragically struggling to survive in the modern world of their conquerors. “The phrase,” according to Maraniss, “would follow (Thorpe) for the rest of his life. Whatever happened to him, good or bad, he was thought of as the embodiment of Lo, The Poor Indian.” (212)

Like Black Hawk, Thorpe became a hero to a diverse population of Indigenous American people across the continent, not just to the Sac and Fox. Yet Maraniss focuses more on the similar ways that prominent members of White society exploited and abused both people. Similarly, he evokes Lo, the poor Indian throughout his biography whenever writing about Thorpe’s struggles in life, particularly pertaining to the difficulties that he faced earning a living commensurate to the fame that he had achieved as an athlete.

In fact, Maraniss first introduces readers to Lo, the poor Indian when discussing the loss of Thorpe’s Olympic medals. As the author points out, those who condemned Thorpe as a professional were, at best, hypocrites. In an illuminating detour, Maraniss recounts the story of future General George S. Patton who competed in the modern pentathlon, a contest that, unlike the pentathlon that Thorpe won, consisted of five events drawn from military skills. Patton did not medal in his event, in part because he misused an opium-based performance-enhancing drug. Maraniss points out that Patton just as easily as Thorpe could have been disqualified for professionalism. “Thorpe was paid a minimal salary to play minor league baseball under his real name, not a pseudonym, for two summers in North Carolina, a sport that had nothing to do with his abilities in track and field. Patton was on the government payroll when refining his skills in pistol shooting and steeplechase riding—and then used opium to enhance his performance during the games. Which man should be punished for what he did?” (216)

Very early in his book, Maraniss foreshadows a story of Thorpe as a masculine hero who will end up emasculated, comparable to warriors that the United States cavalry and the march of “civilization” defeated and controlled in the nineteenth century.

Worse than hypocrisy, however, Thorpe’s Olympic scandal both reveals and foreshadows betrayal. His coach at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Glenn S. “Pop” Warner, encouraged—one could even argue recruited—Thorpe to try out for the U.S. Olympic team despite, as Maraniss convincingly argues, having full knowledge of Thorpe’s summers playing professional baseball in North Carolina. Then, when the incriminating press reports surfaced, Warner feigned ignorance, and then quickly acquiesced to Olympic officials by writing a pathetic confessional letter in Thorpe’s name in order to salvage his own coaching career. After Thorpe left Carlisle, the New York Giants drafted Thorpe to play major league baseball. Yet Giants manager John McGraw, known as the “Little Napoleon,” hardly allowed Thorpe to play. Instead of helping Thorpe develop his considerable talents, McGraw squandered some of the most potentially productive years of Thorpe’s baseball career by using him for publicity to draw fans.

Soon, the arc of Thorpe’s athletic career began to decline, and by the start of the Great Depression, despite the fame that he had once enjoyed, his life became characterized by failed marriages, alcoholism, and poverty. Maraniss, in one of the most interesting passages of the book, draws upon letters that Thorpe wrote to his second wife, Freeda Verona Kirkpatrick. In these, Thorpe alludes to the Lo, the poor Indian phrase himself after reporting being arrested in Florida for public intoxication. Maraniss writes, “As his athletic talents faded, he became increasingly conscious of the ways his Indianness was being viewed in the dominant white society.” (369)

Maraniss is keenly aware of the ways that Thorpe became constrained by narratives that he experienced as a public figure, and he engagingly illustrates this throughout his biography. Indeed, as Thorpe’s daughter Grace once told me in an oral history interview, a contemporary reader might take particular notice of a paradox that defined Thorpe’s life. On one hand, he enjoyed enormous fame and public recognition, which not only involved praise and adornment, but also invasions of privacy, scorn, and judgement. On the other hand, athletes in the early twentieth century, by and large, did not make a lot of money. Unlike top-performing athletes today who earn vast amounts for product endorsements and advertising beyond high-level salaries for playing games themselves, Thorpe found few opportunities to cash in on his athletic glories. At best, he was able to sell the rights to his life story to Hollywood, but even then, the biopic based upon his memoir, Red Son of Carlisle, and renamed Jim Thorpe: All- American, presented a patronizing and distorted picture of his life. More often, Thorpe had to accept bit parts in feature films that barely helped him pay the rent. So Thorpe paid all of the prices of fame (which he never asked for in the first place) but received little in return.

On one hand, he [Thorpe] enjoyed enormous fame and public recognition, which not only involved praise and adornment, but also invasions of privacy, scorn, and judgement. On the other hand, athletes in the early twentieth century, by and large, did not make a lot of money.

In many respects, Maraniss covers the same ground as Kate Buford in her 2010 biography of Jim Thorpe, Native American Son: The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe. Both Buford and Maraniss address Thorpe’s upbringing in Oklahoma, his life at Carlisle, his professional athletic career, and his work in Hollywood, a time marked not only by small film roles but also by activism on behalf of other Indigenous film actors. Maraniss brings to his book his remarkable skills as a storyteller as well, but he also leaves to the reader’s imagination much of what to make of Thorpe’s life and career. From his discussion of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School to his recounting of how Thorpe’s third wife, Patsy, chaotically sold the athlete’s burial rights to a town in Pennsylvania that Thorpe had never visited, there hang a number of unanswered questions about race, gender, and athletic bodies.

Today in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, the borough where Jim Thorpe attended a federally operated boarding school to indoctrinate Indigenous Americans into White, Anglo-Protestant society, there remain imprints of Thorpe’s athletic feats. Dickinson College, the small liberal arts institution in the middle of town, still retains the moniker as the “Red Devils” for its athletic teams, a name that first came about as a reference to the Indigenous students who went to school about two miles away. Carlisle High School’s teams, called the “Thundering Herd,” evoke a less direct and less offensive image of Indigenous life on the plains. A marker on the town square commemorates Thorpe as the Associated Press’s selection for Greatest Athlete of the First Half of the Twentieth Century. And for many years, a variety of businesses around Carlisle use Indian head profiles, like the kind that are found on old nickels and on the helmets of the Washington NFL team, as their company logo.

From his discussion of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School to his recounting of how Thorpe’s third wife, Patsy, chaotically sold the athlete’s burial rights to a town in Pennsylvania that Thorpe had never visited, there hang a number of unanswered questions about race, gender, and athletic bodies.

Sports also remain a core part of public life in Carlisle. Some athletes who have achieved success beyond the Cumberland Valley of Pennsylvania, like University of North Carolina basketball star Jeff Lebo, and former major league baseball player Sid Bream, are White. Others, like Clyde Washington, who played professional football in the American Football League for the Boston Patriots and New York Jets; Lee Woodall, a Super Bowl-winning linebacker for the San Francisco Forty-Niners; and former NBA star Billy Owens, who, along with Lebo, led Carlisle High School to four consecutive state basketball championships, are African American. All of the most celebrated athletes to come from Carlisle are male, even though female athletes have excelled locally and nationally, particularly since the passage of Title IX. Thorpe, ahead of these athletes, gained fame by using his body to benefit White institutions and ambitious White people. For those who, during Thorpe’s life, promoted and wrote about sports in the United States, he represented a vision of Indigenous masculinity that vacillated widely between inspired awe and dismissive resentment. If A Path Lit by Lightening leaves a great deal up to readers, I would suggest that readers use this well-crafted story to ask critical questions about the relationships between sports, race, and gender so relevant to our discussions of athletics in the United States today, and which have their origins in stories like the biography of Jim Thorpe.