With gratitude to my graduate students Daniel Fister, Rachel Jones, and Ashley Pribyl

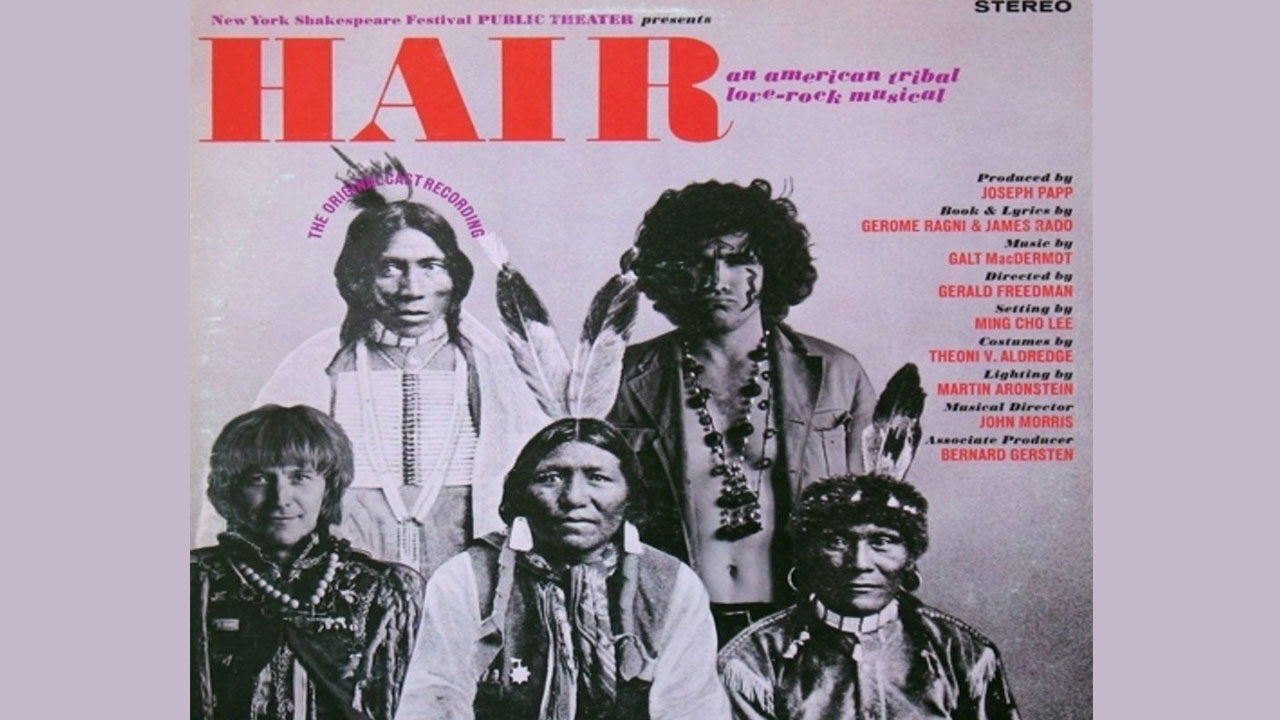

Hair, the self-described “American Tribal Love-Rock Musical,” opened on Broadway in April 1968 and closed just over four years later in July 1972. In its time, Hair—with its ensemble cast of self-proclaimed “hippie” characters—offered several sorts of trips to its Times Square audience.

Among the most unusual, in the Broadway context, were multiple simulated drug trips: one of these occurred early on in the largely plotless show (“Hashish”), as if to declare at the outset that, yes, hippies, a newly-visible group in American society, regularly get high.

A second, more extended drug trip in act two, began with the entire company of twenty-three performers—consistently described as a “tribe”—smoking marijuana together: Gerome Ragni and James Rado’s script indicates, somewhat preciously, that their collective lighting up “should be a rather significant moment.” The musicalized trip that followed dwelled on the experience of the character Claude Berger. At the end of act one, Claude had pulled his draft card out of the fire in which his friends burned theirs. Still subject to the draft, Claude’s act two trip presented a violent fantasy of military deaths across American history with the expected roles reversed: Native Americans kill George Washington’s soldiers; Black Americans kill White Civil War soldiers; etc.

At Hair’s conclusion, Claude has shorn his long hair and is headed off to war. His implied final trip to Vietnam was a familiar one at the time: Hair opened just after the Tet Offensive revealed the tenuous military position of the United States—even in South Vietnam—and the show closed six months before President Nixon ended the draft. The threat of forced service in the controversial war hovered over the show’s plot as well as its making and its entire Broadway run.

Other hippie activities staged for Broadway in Hair include planning protests (none occur onstage), sarcastically calling out racial stereotypes (mostly but not entirely by the Black members of the “tribe”), talking and singing about sex (with more than a few jabs at the emerging gay male culture of the city), dealing with personal relationships (the song “Frank Mills” sung by a girl looking for a boy proves especially poignant), and—as an overarching theme—loudly declaring a general resistance to conventional morality and the older generation. The latter group, represented by characters named “Mother,” “Father,” “Principal,” and “Tourist Couple,” were played by members of the “tribe”: there were no grownups in the cast of Hair. Massive puppets representing the police loomed over the stage but had no substantive role in the action.

A small house built in 1925 and with a seating capacity of 948, the Biltmore had been home to only one musical prior to Hair. The show was an interloper on several levels.

The above content made Hair as a whole into something of a sociological trip for the Broadway audience, who were assumed—in all likelihood, accurately—not to be, themselves, actual hippies. The show presented one distinctive social group to another. For the overwhelmingly White, urban, middle-class Broadway theatregoers of the time, Hair was an invitation to spend some time with an expressive and racially diverse subset of American young people—this expedition to another America came at the price and from the safety of a duly purchased seat in a Broadway theatre. The streets represented on stage were described fairly specifically in the show’s playbill: “Location: New York City, mostly the East Village.” Given this geographical note, Hair could be taken as a substitute for actually journeying downtown and engaging with real hippies.

It took 209 weeks or forty-nine months or just over four years for Hair to rack up 1750 performances during its original run at the Biltmore Theatre on West Forty-Seventh Street. (The show had brief initial productions Off Broadway at the Public Theatre in 1967 and in a nightclub near Times Square in early 1968.) Commercial success for any musical, especially the enduring sort enjoyed by Hair, plays out against an always changing array of other options. Eighty-five other musicals played in thirty-four active Broadway theatres in the Times Square Theatre District while Hair was on the boards at the Biltmore. This essay puts Hair beside select musicals that surrounded it during its time on Broadway. These theatrical contemporaries— all competing for the commercial theatre audience—shed complementary light on each other, especially in relation to key social issues of the time, such as patriotism (the war and the flag), civil rights (the Black/White divide), and the sexual revolution. Considering Hair in its theatrical milieu weaves this unusual show into the fabric of its specific Times Square time. In reciprocal fashion, sampling the Broadway musicals around Hair reveals the genre as directly engaged with American culture during an especially volatile passage. This contextual and comparative essay does not look for lines of influence running between these shows. Instead, what follows explores shared and contrasting tropes and topics across the four Broadway seasons when Hair was part of the Times Square mix—perhaps in the way frequent theatregoers might compare their experiences at a variety of shows or might try to work out how Hair, an unusual evening at the theatre, could be made to fit into its Broadway context.

Theatregoers’ choices are inevitably limited by the shows running on any given week and by the availability and cost of tickets. In Hair’s case, simply finding a Broadway theatre owner willing to house the show proved a challenge. After refusals from the major Broadway theatre owners, the Schuberts and the Nederlanders, first-time producer Michael Butler convinced David J. Cogan, owner of the Biltmore, to give Hair a chance to find a Broadway audience. A small house built in 1925 and with a seating capacity of 948, the Biltmore had been home to only one musical prior to Hair. The show was an interloper on several levels.

Hair‘s status as a wartime musical proves key: American involvement in Vietnam was raging when the show appeared, and the conflict proved central to the show’s engagement with its moment, a time when conventional notions of patriotism were under tremendous pressure. Stage directions in Hair’s script call for three sorts of American flags: versions of the Stars and Stripes from 1776 and 1967, as well as the 1776 Culpepper Minute Man flag, which depicts a coiled snake and the motto “Don’t Tread on Me.” (The last of these was adopted by the conservative Tea Party in 2009.) Members of the “tribe” hint at but do not actually burn the flag onstage: instead, they sing a twangy satire of jingoistic patriotism called “Don’t Put It Down,” a perhaps directly offensive moment of parody aimed at conservatives—one of relatively few in the show.

A much more reverent if still disputatious show exploring patriotic themes played close by Hair: 1776 opened one block south at the Forty-Sixth Street Theatre (now the Richard Rodgers) in March 1969 and ran for twenty-one months. 1776’s overture approximates the sound of an eighteenth-century military band—a sharp contrast to Hair’s overture-less, rock opening “Aquarius” with its amplified and processed sound design. Hair relied on an “excellent sound system” (essential to the show, according to the script) and the use of visible microphones onstage: both were unusual, as was the show’s employment of a sound engineer to balance the mix of voices and instruments. (By the 1980s, all Broadway musicals were amplified.) The sheer volume of Hair by comparison to any show running in its time is important to note. The voices of hippie youth were innovatively and objectively louder than others heard in the Broadway theatres at the time.

The almost entirely male cast of 1776 enacts the struggle of the Continental Congress to agree on the text of the Declaration of Independence. The show’s consensus finale assembles a patriotic tableau vivant—the birth of the nation’s political establishment by way of a roll call of the White men who signed the document set to the ringing of the Liberty Bell; an unconventional close for a musical but for some audiences, no doubt, a stirring coup de theatre. Despite tension in act two over the elimination of a statement on slavery in the original Declaration’s text, the reverential politics of 1776 tilt conservative within the late 1960s present—except perhaps in the inclusion of the wives and (sanitized) sex lives of Founding Fathers John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. 1776 presents the nation’s founding as a debate among articulate, grumpy, wealthy, middle-aged, White men prodded throughout by the show’s abrasive if triumphant hero, Adams.

The sheer volume of Hair by comparison to any show running in its time is important to note. The voices of hippie youth were innovatively and objectively louder than others heard in the Broadway theatres at the time.

The sole exception to old White men debating independence (or battling with and cooing to their wives) is the show’s unusually subdued act one closer, “Momma Look Sharp.” This battlefield ballad sung by a young courier fresh from General George Washington’s army suddenly brings the younger generation and military service—a potent topic outside the theatre—into this historical show about powerful adults. In this startling yet quiet moment, 1776 acknowledged the generation gap—a perceived crisis of the time that Hair thoroughly and loudly troubled from the opposite side.

1776 prevailed over Hair to win the 1969 Tony Award for Best New Musical.

The notion of a musical built around a group of strongly affiliated people—a “tribe” in Hair’s lingo—was hardly new: the 1964 hit Fiddler on the Roof ran during the entirety of Hair’s time on Broadway, moving from the Imperial to the Broadway Theatre—both significantly larger than the Biltmore. Fiddler’s “tribe,” a Jewish village in Czarist Russia, is a model of multigenerational balance. The papas, the mamas, the sons, and the daughters each introduce themselves in turn in the opening number, “Tradition,” before singing their respective melodies in harmonious if raucous, counterpoint. “Aquarius” functions just like “Tradition” as an opener that distills the larger idea of the show to follow in a joyous and collective musical celebration.

In this early moment, Fiddler presents a functioning community where traditional values and roles hold things together. But Fiddler’s story moves almost immediately into a series of disruptions caused by daughters who want to choose their husbands and intolerant political powers who force the destruction of the village itself. The adults in Fiddler come to understand and embrace these changes in a model of adaptability unimaginable for the “mom” and “dad” caricatures of Hair.

Of course, Fiddler’s generational and ethnic conflicts remain circumscribed within a politically powerless if expressively rich minority community. Hair’s diverse tribe of protesting youths includes no elders and sets itself against an imperial establishment feeding its desire for global domination with the bodies of the young and the poor—and at the time, literally destroying villages (ostensibly “to save them”) in Vietnam.

Another long-running Broadway “tribe” from Hair’s time famously bared it all. The adult-oriented musical Oh! Calcutta! opened a year after Hair and closed twenty months later—when Hair still had over a year left. (A revival of Oh! Calcutta! held the stage from 1976 to 1989, making it among the longest-running productions in Broadway history.) If Hair centered on long-haired youths on the street, Oh! Calcutta! served up sexually-liberated adults in frank if sophomoric—now mostly offensive—skits about heterosexual sex and relationships. Brief nudity at the close of Hair’s act one was blown open by full nudity throughout Oh! Calcutta!, beginning from the opening number when the cast dropped their white robes. In Oh! Calcutta!’s final scene, members of the cast speak aloud thoughts they imagine are going through the minds of the audience: one such line says of the show, “This makes Hair look like The Sound of Music.”

Hair, with its very loose plot, and Oh! Calcutta!, a thematic revue, stand out as shows that defied the existing conventions of the musical to explore unconventional approaches to life in the contemporary moment. Drawing on different if adjacent social revolutions, these two shows alike reveled in removing any limits on the words that could be said or topics that could be discussed. Hair’s deadpan list song of sexual acts, “Sodomy,” for example, almost dares respectable folks not to get up and leave—“why do these words sound so nasty?,” asks the lyric. The explicit nature of both shows surely limited their audiences—at least to the elimination of families—and, reciprocally, perhaps brought in curious patrons unlikely otherwise to go to a musical.

Broadway musicals regularly select a single socio-economic stratum of the city and present one group of New Yorkers as a self-contained whole set apart from the actual diversity of the city. Hair presented East Village hippies. Stephen Sondheim’s Company—opening midway through Hair’s run at the Alvin Theatre, five blocks uptown from the Biltmore—presented affluent, professional, White, upper-middle-class Manhattanites. Company, like Hair and Oh! Calcutta!, explored the new sexual modes and mores within a defined urban context (mostly above the streets in apartments, likely on the tony Upper East Side) and a decidedly liberal ethos. Company’s characters dissect the value of marriage in purely personal terms as a choice made in the interests of individual happiness, a kind of abstract “Being Alive.” There are no children here, although some of the older couples might be understood as the parents of a youth in Hair. Company’s affluent and White “tribe,” among them the privileged but bored ladies who lunch, contrasts sharply with the street-level youths of Hair: the latter—personally threatened as some are by the ongoing war—are politically engaged, while the former exist in sublime isolation from politics.

None of the above representations of New York or the contemporary moment on the Broadway stage, however, included the increasingly visible, post-Stonewall gay culture of time. Only Applause—opening about two years after Hair—showed, indeed celebrated, this new aspect of the city. Early on in Applause, the show’s central character, Broadway star Margo Channing, goes to lively gay dance club in Greenwich Village—unsurprisingly, the joint is full of her fans (the show was filmed for television in 1971). For all their edgy sexual exploration, neither Hair nor Oh! Calcutta!—the latter by explicit design—admitted to the emerging public presence of homosexual men. Even Company shied away from this newly public variety of sexual freedom: a scene where a married male character propositioned the single man at the center of Company was cut in rehearsals and only re-introduced in the 1995 West End and 2006 Broadway revivals. Hair, as noted, includes multiple references to homosexuality—almost all function as sophomoric humor or moderate panic passed between young male characters.

Hair, with its very loose plot, and Oh! Calcutta!, a thematic revue, stand out as shows that defied the existing conventions of the musical to explore unconventional approaches to life in the contemporary moment.

Among all the above described shows dealing in some way with the sexual revolution, only Hair also engaged questions of race. Hair could do so because its cast included Black and White performers. In this, Hair stands out as that always rare species: a Broadway musical with a racially diverse cast playing characters who speak and sing about their racial identities. Hair attacks these racial topics in provocative if always ironic, somewhat formal ways. The potential energy provided by an interracial cast comes out with special punch in the “Black Boys” / “White Boys” sequence, in which two opposing all-female trios—one all-White, one all-Black (a la The Supremes)—objectify in teasing terms the sexual charms of men of the opposite color. The two songs’ respective lyrics display the relative imbalance of racial stereotypes: “White boys” are exoticized in novel terms for their hair like “Chinese silk”; “black boys”—predictably—offer “delicious, chocolate-flavored love.”

Hair overlapped with the start of a decade or so when Broadway welcomed a series of Black-cast musicals tackling questions of racial history, representation, and justice in commercially successful and critically lauded ways. Purlie, the first of these, opened mid-way through Hair’s run and lasted twenty months. A conventional book musical set in the South, Purlie rather gently explored the stereotypes of Black performance by having a White character try without success to play Black music. A nice but not uncritical Black woman lets him know, repeatedly, “that ain’t it, honey.” By show’s end, of course, he figures it out.

Hair, characteristically, took a more aggressive tack. Hud, the most prominent Black man in the cast, sang “Colored Spade” early in act one. The lyric catalogs racial stereotypes—including the N-word—from Uncle Tom to shoeshine boy to “President of the United States of Love.” Throughout, Hud and his backup singers confront the implicitly White audience with the accusation, “so you say.” This assertive challenge by a Black character—a grooving “I am” song listing what he is not—found a much stronger echo in the Black-cast musical Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death, a startlingly serious show that played for nine months at the end of Hair’s run at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, literally steps from the Biltmore on the north side of West Forty-Seventh.

Created by Melvin Van Peebles—and thus among the tiny handful of musicals from across Broadway history authored by African Americans—Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death began with the Star-Spangled Banner. The script describes this opening as a test of the audience: “The song is played straight, not jazzed up or solemned down, and the house lights stay up full so folks can make their statement and be seen and dig other people making theirs. Decisions, decisions. Does standing mean you want crackers on the Supreme Court? Does it mean you have forgotten the Vietnam casualty lists, or does it mean you are remembering the guys who got it at the Alamo or the Battle of the Bulge?” This pointed, even barbed start positions Ain’t Supposed to Die as both a show that engages patriotic feelings (like Hair and 1776) and a “tribal” show (like Hair, Fiddler, and Company) where the audience’s, and by implication America’s, status as a unified group is measured. With a set representing “a multi-leveled composite of all the urban black reservations,” the show unfolds (like Hair and Oh! Calcutta!) as a loose series of numbers and scenes, with often violent and graphic content, representing a composite view of the urban Black experience—in its way, a catalog of racial stereotypes (just not ones heretofore found on Broadway). An extended, physically abusive confrontation between a pimp and a prostitute over a five-dollar bill is among the roughest scenes in all Broadway musical theatre.

Among all the above described shows dealing in some way with the sexual revolution, only Hair also engaged questions of race. Hair could do so because its cast included Black and White performers. In this, Hair stands out as that always rare species: a Broadway musical with a racially diverse cast playing characters who speak and sing about their racial identities.

Throughout, White characters, such as the police, are represented by Black actors wearing white masks. Ain’t Supposed to Die ended with the shooting by police of an innocent young Black man who dies slowly, desperately running for as long as he can into a future he is denied. “He was just a baby,” his mother lamented loudly. At this climax, a character who has not spoken to this point, called the Crazy Old Bag Lady in the script, turned and faced the audience—White by implication—and repeated over and over the phrase “Put a curse on you” between descriptions of the specific challenges faced by Blacks in the United States. Nothing in Hair got close to this type of direct confrontation—a video of the sequence from the 1972 Tony Awards is available on YouTube—and the continued killing of young Black men at the hands of police on American streets in the twenty-first-century makes this scene tragically still relevant. Ain’t Supposed to Die remains a resonant topical musical for our contemporary moment: the same cannot be said for Hair.

Indeed, the violence of the urban Black streets represented in Ain’t Supposed to Die contrasts strongly with the total absence of intimidation on the streets for Hair’s tribe. Hair opens up a space of absolute social freedom, an age-segregated but racially integrated (still mostly White) utopia of the young, a privileged zone of apparently unpoliced expression. It is completely safe—one reason, perhaps, that the Broadway audience felt comfortable going and observing.

Hair was understood to express its time with particular potency. The success of several songs—among them “Good Morning Starshine”—as well as the show’s cast album on the pop charts made for an unmistakable and unusual connection between Broadway and popular music in the rock era. But the times were changing quickly and by its 1972 close the world Hair put on stage was arguably already of the past. As noted, Hair closed just months before the end of the draft. And with the further passage of time, Hair—revived on Broadway unsuccessfully in 1977 and successfully in 2009—has come to express its particular moment in a re-performable form: it is a late ’60s show that allows for a sensuous re-creation of the colorful hippie ethos even as the urgency of the confrontations Hair enacted, particularly around the war in Vietnam, have receded into historical memory.

Broadway has long been a space where past decades are afforded live re-creation—always with the goal of exploiting audience nostalgia for present commercial purposes. Two shows that ran beside Hair embodied this strategy and, in their way, hinted at the role Hair would play in its afterlife.

The success of several songs—among them “Good Morning Starshine”—as well as the show’s cast album on the pop charts made for an unmistakable and unusual connection between Broadway and popular music in the rock era. But the times were changing quickly and by its 1972 close the world Hair put on stage was arguably already of the past.

No, No, Nanette opened in early 1971 and over its two-year run returned the heady pleasures of 1920s musical comedy to Broadway—complete with a tap-dancing chorus, absent from the musical stage for decades. The show re-asserted the potency of a historic Broadway style and—with some lacuna—tap remained an expected (or at least possible) aspect of musical comedies, regardless of their settings, in most subsequent Broadway seasons. But No, No, Nanette was not really a 1920s musical comedy: it was, instead, a 1970s version of the 1920s, the earlier decade rendered in a legible form for contemporary audiences.

In similar fashion, if closer to living memory, Grease delivered a 1970s vision of the 1950s. A huge hit, running from 1972 to 1981 and totaling 3388 performances, Grease began its long residence on Broadway just a month before Hair closed. Peopled by White, working-class high school kids in the 1950s, Grease was a surprisingly profane show, with multiple uses of the F-word, much frank sex talk, and a teen pregnancy scare in the plot—all, however, moderated by the fundamental innocence of the characters. Such innocence is also a hallmark of Hair—which includes one character who is kicked out of high school for his long hair.

However, Hair in its Times Square time was not a period piece. It was not nostalgic in its moment—even if it is, perhaps, a nostalgic or just a period piece now. In this, Hair proves itself to be—in some sense, at least—real.