A soul brother made it.

Now ain’t that a groove.

—James Brown, “America Is My Home,” released in 1968

In the Philadelphia of my boyhood, teenaged street gangs prided themselves on having one boy with fast hands, who could, as was said, “stick and move.” That boy was called the warlord. He was not the leader of the gang. He was the best fist-fighter. I attended school with two boys who not only became professional fighters but champions. Jeff Chandler, who was bantamweight champion from 1980 to 1984, was a schoolmate at Nebinger Elementary School. (Maybe Chandler went to McCall or Meredith, not Nebinger, although he hung around Nebinger a lot. The Black kids called Meredith “Murder.” I do not know why. That school was no worse than any other public school in the Southwark district of Philadelphia.) Matthew Franklin, who became Matthew Said Muhammad and was light-heavyweight champion from 1979 to 1981, was at Bartlett Junior High while I was there. If these boys were gang members, and they might very well have been, Chandler with the Fifth Street Gang, and Franklin with Thirteenth Street, they would surely have been warlords.

When I was a teenager until I was well into my twenties, I would, once a month, buy the latest issues of the leading boxing magazines, The Ring, KO, and such titles. I would go home, spread them out on my bed, and go through them, reading one article at a time from each and savoring each, as a woman might with boxes of bonbons. In this way, with the help of the local papers like the Philadelphia Daily News and The Philadelphia Inquirer, I especially kept up with the Philly or near-Philly fighters of the 1960s and ’70s such as Bad, Bad Bennie Briscoe, Stanley “Kitten” Hayward, Eugene “Cyclone” Hart, Ruben “Hurricane” Carter, George Benton, Gypsy Joe Harris (who was blind in one eye and yet still had a boxing license), Sammy Goss, Joey Giardello (who successfully sued director Norman Jewison for how he was depicted in the 1999 film, The Hurricane), Joe Frazier, Tyrone Everett (murdered by his girlfriend), and many others. Philly produced a lot of good fighters. It was a tough town. It probably still is, with lots of working-class types in provincial neighborhoods, where guys who were “good with their hands” were respected. You could see many of these guys at a reasonable price fight at a place called the Blue Horizon, the mecca of boxing. I was looking for an advertisement, first, of promoter Herman Taylor in the 1960s, then, of the latest Russell Peltz fight card in the early 1970s. What happened to these ring men, with fast hands and “the moves,” was both gruesome and glorious. It was good to be alive then and know boxing, if you had the stomach and the heart for it.

I. The Emperor of the Fifth Ward

In his 1995 autobiography, boxer George Foreman wrote about growing up in the “Bloody Fifth” Ward in the Black part of Houston in the 1950s and ’60s:

Every weekend someone got killed in a knife fight. And if your enemies didn’t get you, the police would. . . . The aim of the police was to tame you, to break your spirit: to turn a wild stallion into a stable horse. I remember one courageous boy, filled with too much liquor and the boxing skills he’d learned in prison, standing up to the police. After he opened his mouth a little too loud, they got him down and delivered so many savage kicks that doctors had to reconstruct his torso with some of the tendons and ribs. Another boy was beat so badly that he never talked again before dying in his twenties. Sooner or later, all the tough guys got beaten by the police. (George Foreman and Joel Engel, By George: The Autobiography of George Foreman, Villard Press, 8-9)

Or their mothers, as Foreman’s mother tried to break him before the police could, beating him “often and hard—crucial beatings, strategic and tactical, administered completely out of love and concern. . . . She wanted me to be more afraid of what she would do to me if I disobeyed her than of any trouble I might get into in the streets.” (By George, 9)

None of this helped Foreman, who grew up dirt-poor and in a single-parent home. He became a bully who got into fights to terrorize other boys. He never finished junior high school, largely because he hardly ever went to school, and when he did, he did not study. His teachers saw him as trouble: incorrigible and stupid. The teachers performed triage and hoped that a kid like Foreman would eventually disappear, to invest their attention in more promising students. By the time he was a teen, he was a practiced mugger, beating and robbing people, a full-fledged criminal. “For me in those days, the law was the law of the jungle, where the end justified the means. Survival.” (By George, 16, italics Foreman)

Whatever could be said about Foreman, it was certain, at this point, that he had not been tamed, and he had not been broken. He had not even been dented. Life belonged to the most brutal, and no one felt sorry for those who lost to the most brutal.

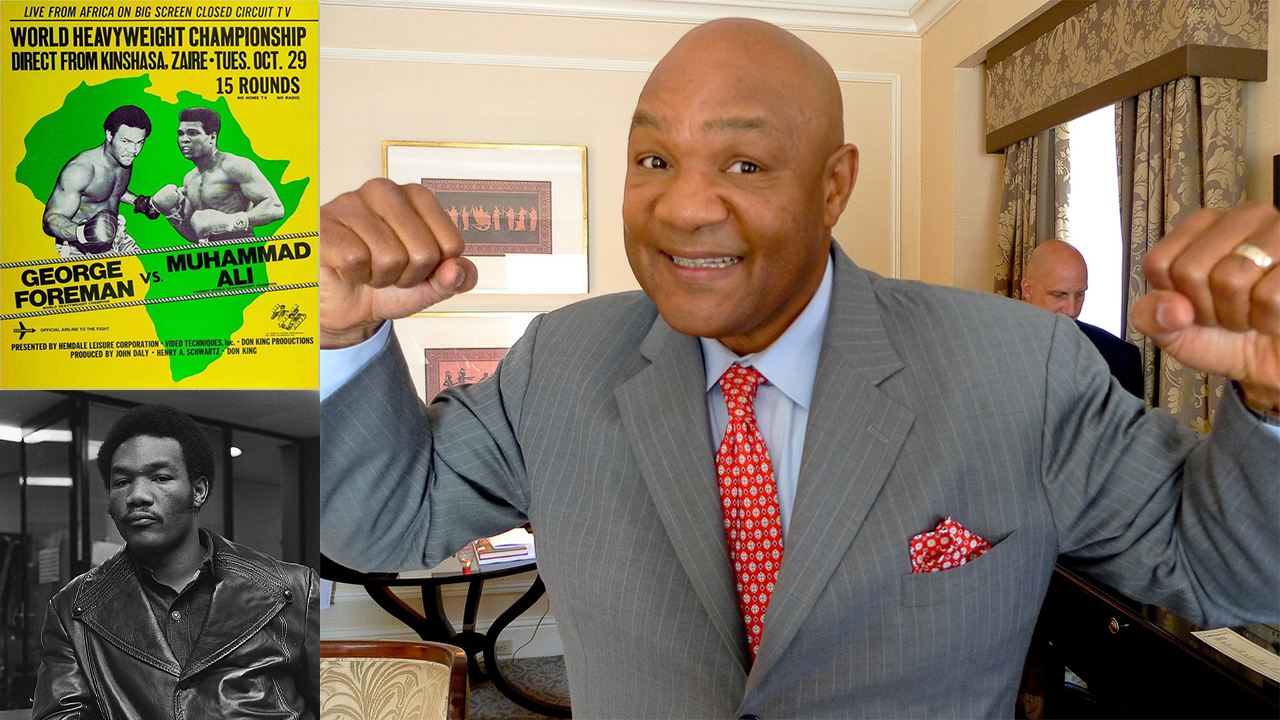

George Foreman at Amsterdam’s Airport Schiphol in 1973. (Wiki-CC)

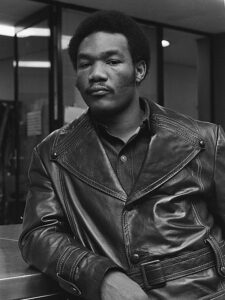

Cassius Clay, the Louisville native who would grow up to become Muhammad Ali, became a boxer when someone stole his bicycle when he was 12. Clay was that kind of Black kid, from a two-parent home (even though his parents’ marriage was rocky), who had been given a bicycle. Clay would wind up taking boxing lessons from a White Louisville police officer, Joe E. Martin. George Foreman was the kind of kid who would have stolen Clay’s bike and beat him up for good measure if he got the chance. In 1974, they met as professional fighters in a ring in a country at that time called Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). Clay, now Ali, finally got his chance to avenge the theft of his bicycle against someone who might have been like the kids who took it. Foreman got his chance to further intimidate the kind of Black kids who owned bikes.

II. The Quartet

Everybody loses but you can’t just die!

—Geraldine Liston, wife of heavyweight boxer, Sonny Liston1

The death of former heavyweight boxing champion George Foreman on Friday, March 21, 2025, signaled the absolute end of an era, not just in sports history but in American political and popular culture. He was the last of the quartet of Black boxers who defined boxing in the 1970s, led by Muslim dissenter and charismatic trickster Muhammad Ali, the maestro, the Greatest.

But Ali could not have survived and thrived as a competitive athlete without serious rivals who were a threat to his reign, who could possibly (and, on occasion, did) beat him. So enter the other members of this quartet: “Geechee” South Carolina boy turned Philly proletarian slick Joe Frazier; star athlete, ex-Marine, and Hollywood body beautiful Ken Norton; and hungry bully boy turned preacher George Foreman. Frazier would fight Ali three times, winning in March 1971 at Madison Square Garden in one of the most hyped sporting events of the twentieth century, and then losing to Ali in a non-championship fight at Madison Square Garden in 1974 and again in a championship match in 1975 in the Philippines, famously dubbed by Ali, “the Thrilla in Manila.” Ken Norton fought Ali three times, beating him in a non-championship fight in March 1973, which stunned the boxing world as Ali was heavily favored to win. Ali barely won the rematch, which occurred six months later, also a non-championship fight. In September 1976, Ali barely won again, this time a championship fight that Norton felt certain he had won. Ali and Foreman fought only once in what was the biggest fight of the 1970s and both men’s careers. Foreman was heavily favored to win as he was younger, punched harder, and had easily knocked out both Frazier and Norton in essentially non-competitive matches, both of whom had given Ali so much trouble. But shockingly Foreman would lose this bout. In a way, Foreman never had a chance. Ali psyched him out. Ali hated being in Zaire as much as Foreman but he pretended that he did not. Ali played to the Africans. Foreman ignored them. “This was clearly Muhammad Ali country,” Foreman wrote, “Sentiment in his favor colored how everyone looked at me. . . Most people wanted him to win back the title as much as he did. . . . I realized that no matter what happened in the ring, I couldn’t win for losing.” (By George, 107) That made all the difference. It was this fight where Ali came up with the fitting name “rope-a-dope.”

Boxing is a sucker’s game. Look at how Ali, Frazier, and Norton wound up: broken down, aged, and unable to piss without remembering the blows they took. And Black Power, in this instance, was capitalism as a chimera.

The Ali-Foreman fight was a golden moment of Black Power in the 1970s, two Black boxers competing for the championship in an African country. The fight was promoted by Don King, a Black man who would become a major player in boxing in the 1970s, ’80s, and into the ’90s. Yet there was something about this that seemed a façade. Why would a poor African country think that putting on a big prizefight was a good investment for its people? Why would any poor nation? Andrew R. M. Smith wrote in No Way But to Fight: George Foreman and the Business of Boxing (University of Texas, 2020) that after Mexico’s Olympics, “other nations [tried] to prove their sovereignty and virility by hosting an international sports mega-event . . . . [In] the deregulated world of boxing, even the biggest bouts could be bought, sold, or usurped.” (116) So, developing nations like Jamaica, where Foreman fought Frazier for the first time (1973), or Venezuela, where Foreman fought Norton (1974), were venues for high-priced boxing matches. Foreman, in fact, did not fight in the United States in either 1973 or 1974. This seemed almost identical to the thinking of the movers and shakers of Shelby, Montana, who put on a heavyweight champion fight in 1923 between champion Jack Dempsey and Tommy Gibbons. The fight nearly bankrupted the town, and it certainly gained nothing by hosting it except being considered the dupes of the world when Dempsey’s manager, Jack “Doc” Kearns, ran off with the gate receipts after bilking Shelby for everything he could get. Few towns have ever been so completely ravaged without a shot being fired. Boxing is a sucker’s game. Look at how Ali, Frazier, and Norton wound up: broken down, aged, and unable to piss without remembering the blows they took. And Black Power, in this instance, was capitalism as a chimera.

(Library of Congress)

But Norton, Ali, Frazier, and Foreman shaped the 1970s, the Black 1970s. Together, these men provided the most compelling range of Black masculinity that had been seen in American popular culture in such a compressed period of time, from 1970, the time of Ali’s return to the ring after his three-plus years of being denied a license to fight because of his conviction for violating federal conscription laws to 1976, when Ali beat Norton in their third fight. Ali would fight six more times after the third Norton fight, losing three of them, including the last two fights of his career. Norton and Frazier would not make comebacks, but Foreman would. He had a second act.

Interestingly, Norton never fought Frazier, perhaps because they were friends, perhaps because they had the same trainer for a time. It could not have been because Norton had been Frazier’s sparring partner, because Ali fought former sparring partners twice, Jimmy Ellis in 1971 and Larry Holmes in 1980, winning the first, losing the second because by then Ali was shot as a fighter. Fighting your sparring partner in a championship match was giving him a break, a chance to make some decent money.

Whatever could be said about Foreman, it was certain, at this point, that he had not been tamed, and he had not been broken. He had not even been dented.

Ali, as heavyweight boxing in his era was dominated by Blacks, could not take advantage of the one thing professional boxing historically loved to sell, the racial or ethnic difference between opponents. What boxing sold was symbolic, individualized race wars. (Doubtless, this was better than having real, non-symbolic ones.) So, Ali simply re-fashioned his opponents as “White” or tools of the White establishment, honorary Whites, so to speak. Voila, a race war between two Black men. There was a certain sincere, if misplaced, fervor to this in the 1960s when Ali, a fresh convert to Islam, fought Sonny Liston, Floyd Patterson, and Ernie Terrell and was on a mission from his God, Allah.

This was more theatrical and threadbare in the 1970s, an act that did not quite age well in the fading moments of the Black Power/Black Arts Movement, when activism of a sort seemed to be panting from exhaustion, frustration, and, possibly, boredom. Ali’s racial reductionism continued to work well enough at the box office (after all, he was the most famous man on the planet) and fed the legend of Ali as a Black Diasporic hero. But these men, as it turns out, were distinct Black male personalities. And their individual differences mattered to both Black and White audiences of the time. In fact, their individual differences mattered to Ali because he could not have made the men his foils so successfully had they not been so different: the inarticulate “country boy” Frazier, the tough, hard, thoughtful ex-Marine Norton, and the recalcitrant, silent, moody Foreman. Despite the façade, Ali was no less fighting for White interests than they were. Ali depended on White admiration and dislike, and White money, in order to remain an act as he aged. That is to say, none of these boxers could help but fight for White interests of some sort. Now, they are all dead: Frazier (2011), Norton (2013), and Ali (2016). But Foreman outlasted all of them. In a way, he beat them all too, as he wound up making far more money than they all did combined.

III. Pitchman

And who was I? The goof who’d waved the American flag.

—George Foreman (By George, 107)

George Foreman is a testament to Lyndon Johnson’s ambitious anti-poverty push of the mid-1960s. He became the “poster child of the Job Corps” program, as he wrote (By George, 42), which was meant to offer young men like him a second chance. The program was a reinvention of FDR’s Civilian Conservation Corps, which lasted from 1933 to 1942 and geared for unmarried young men between the ages of 18 and 25. The most important thing that Job Corps did was get Foreman out of Houston. He wound up at a camp in Oregon. It was here that he first interacted socially with Whites (an important development in his maturation), started to read stories like Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” and began to learn the craft of boxing. Despite his size, he had not succeeded at athletics while he was in school; his attempt at football ended when the coach caught him smoking, a cardinal sin in the coach’s eyes and punishable by being paddled. “I never went back to football practice. And without football I stayed out of school completely; it had nothing to offer me.” (By George, 15) While in Job Corps, he stopped, not suddenly but steadily, being the thug who just beat up people for no reason. Boxing was the ticket out of whatever anti-social tics that ailed him: “Boxing was my best opportunity to buy a decent life for my mother. That’s all I cared about. In fact, I cared so much that I even managed to quit smoking.” (By George, 47)

Job Corps and boxing led to the Holy Grail of amateur athletics, the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. Winning a gold medal in boxing at the Olympics had launched the careers of Floyd Patterson (Helsinki, 1952), Muhammad Ali (Rome, 1960), and Joe Frazier (Tokyo, 1964). Foreman did not have to worry about the boycott being organized by sociologist Harry Edwards to protest the presence of South Africa, among other things, because only star athletes, like Lew Alcindor (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), whose absence would make the news were being recruited. Foreman was nobody from nowhere then. Who would care if he did not show up, as nobody would know that he had even been invited to compete. Foreman distinguished himself in another trenchant way from those being asked to boycott: “Fact is, their pitch was most successful with guys like Kareem, who were used to radical messages because they attended college on campuses already hot with protests about the war in Vietnam. . . . Whether the students’ anger was righteous, I don’t know. I knew only that their world wasn’t the one I saw. Maybe I was ignorant, but even at its most desperate and violent, the world I’d grown up in hadn’t made me mad. . . . Yes, I had been hungry. But I always believed I would develop skills and earn a living for me and my family. How could I protest against ‘the establishment,’ when that establishment had created the Job Corps for guys like me? . . . Besides, I’d experienced prejudice in a way that Harry Edwards and his colleagues maybe had not. Remember, my family and teachers in grade school had shared my physical characteristics. But that hadn’t prevented them from prejudging me and the type of man I might become.” (By George, 55)

George Foreman with President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968 (Library of Congress)

Foreman’s reasoning was that if the Job Corps had done what it was supposed to do for people like him why did he have to protest and against what? Besides, like a good many Black folks from the lower end, he was a little skeptical about the glorious solution of “race over all,” or some such political combination of chauvinism and solidarity that signified commitment. The people who did not believe in him when he was a youth were other Blacks, not Whites. So, he did not need to prove something to Whites. He had no reason to question his authenticity, to seek it, or to prove it. He was not angry because he did not need to be in order to prove himself authentically Black. This view, too, was partly a function of his class and partly a function of his own temperament.

South Africa did not participate in the 1968 Games. The boycott was called off. And Foreman won the gold medal. Being an Olympic champion assured him not only a professional boxing career but a turbo-charged entry into that realm, already a box office draw. But calling off the boycott did not call off a protest. Black American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos made their way into history on October 16, 1968, by offering a clenched fist salute to the National Anthem when awarded their medals, which promptly got them a one-way ticket home. “. . . I considered John’s and Tommie’s protest to be a faddish statement of the times—like wearing a dashiki, long hair, faded blue jeans, an Afro,” Foreman wrote. “Expelling them from our family [the Olympic Village] seemed an injustice.” (By George, 56) What thoughts Foreman had of withdrawing because of the response to the Smith/Carlos incident did not last. When he won his gold medal, beating Soviet champion Ionas Chepulis on October 23, he did what was customary: walk to each of the four sides of the ring and bow to the crowd. He waved a small American flag he had hidden in his trunks as he did so, a not-so-spontaneous gesture of a sort. He claimed it was not a “counterdemonstration” to Smith and Carlos, but he had to be smart enough to know that it would be interpreted as such. He had to be self-aware to know that if White America vilified Smith and Carlos for being Black ingrates, he would be lionized for publicly honoring his country. “. . . there was a big element of patriotism in what I did; being in the Olympics, you couldn’t help but love your country more than before. But I meant it in a way that was much bigger than ordinary patriotism. It was about identity. An American—that’s who I was. I was waving the flag as much for myself as for my country.” (By George, 60) Foreman was grateful for being an American, a position that many, if not most Blacks found, at the least, troubling, at worst, a grift, pure Uncle Tomism. In a sense, at this moment, Foreman had already found his calling, as a pitchman. He was selling Black patriotism, and during the era of Black Power and anti-Vietnam War activism, that was a product that more than a few people found not only attractive but valuable. In the summer of 1968, Soul Brother No. 1, James Brown, released “America Is My Home,” with lyrics not sung but recited, “a patriotic song,” 2 Brown called it:

America is still the best country, without a doubt

And if anybody says it ain’t you just try to put ’em out 3

Brown would feel that way his entire life. He was stingingly rebuked by the Black militants of the time and even members of the liberal Black civil rights establishment for the song. What critics failed to hear in the song was the lyric, “Now in Augusta, Georgia/My home town/On the auditorium steps/Where I used to shine shoes/Now I go there, Jack/Fill up the joint/Don’t sing a thing but Rhythm and Blues.” What Brown is saying is that he did not make it in America as some sort of assimilated entertainer, an imitation White. He made it as a Black performer making Black music. He was NOT a sell-out, as his critics glibly said. He was saying that America permitted him to make it on his own terms. Brown might have misread his circumstances but to call him an Uncle Tom was to misread him in an utterly knee-jerk reductionist way. Later that summer, he released “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud),” which restored him in the good graces of the race. “Say It Loud” was never meant to repudiate “America is My Home.” It was meant to be a distraction from it, a magician’s misdirection. Brown was one of the relatively small number of Blacks in America who would have appreciated Foreman’s gesture in Mexico.

The people who did not believe in him when he was a youth were other Blacks, not Whites. So, he did not need to prove something to Whites. He had no reason to question his authenticity, to seek it, or to prove it. He was not angry because he did not need to be in order to prove himself authentically Black.

The patriotism of Black Americans is a complicated subject. Anti-Americanism is hardly surprising considering the country’s history; being Black and being American are two irreconcilable things, as W. E. B. Du Bois once suggested; but pro-Americanism should not be so surprising either, if a Black American thinks being a citizen, even if persistently stigmatized, sometimes inconvenienced, and occasionally overtly persecuted, of the most powerful country in the world to be worth something akin to being a citizen of Ancient Rome at its height. Stanley Crouch once told me that while Blacks in nineteenth-century America hated slavery and racism, many were fascinated by America itself, by the energy of it, by the idea of it. “Albert Murray told me that,” he said. “There is the myth of Moses but there is also the myth of Joseph.”

Foreman’s flag-waving became nearly as noted as the Smith/Carlos protest. After the Olympics, Foreman appeared on numerous television shows. Before he became more aloof during his years of his first championship reign, he had a pleasant, sellable personality that adumbrated the personality he would adopt when he shaved his head and became everybody’s favorite uncle. He campaigned with Democratic presidential nominee Hubert Humphrey. The Republican nominee had actually approached Foreman before the Olympics about joining his campaign. Foreman turned him down because he had heard that Nixon wanted to cut Job Corps. Humphrey supported it. Foreman was not such a political naïf as he led people to think. Of course, he was castigated and ostracized by many Blacks in Houston. But he was on the road to becoming heavyweight champion of the world. He had a name, and even if his skills were not polished (Foreman was nobody’s boxing technician), he was big, strong, with a hard punch, and a willingness to train and follow his trainers’ instructions. What were his Black critics, those loudmouthed, street losers he left behind, going to be? Nobody was buying what they were selling. What Foreman learned early on was this: do not try to sell unhappiness. People are already more unhappy than you think.

• • •

After his humiliating defeat to Ali in 1974, Foreman went through what can only be described as a prolonged obsession: trying to get a rematch with Ali. He appeared on television shows, publicized himself much more than he did during his champion days. But his boxing career sputtered as he beat Joe Frazier again, and such lackluster boxers as Scott LeDoux and Pedro Agosto. On April 26, 1975, he fought five guys in one night, three rounds each, knocking most of them out. It was an embarrassing stunt. Probably his most impressive win was knocking out stalwart Ron Lyle in a five-round brawl he nearly lost as each fighter was knocked down; Foreman went down twice in the fourth round. But his loss to slick boxing Jimmy Young in 1977, who outfoxed, outmaneuvered, and outran Foreman, brought down the curtain on Foreman’s first act. It was a fight Foreman was supposed to have won easily, and he had moments when he could have. Foreman wilted as the fight went on and lost the decision, his first fight that went the distance. What happened to Foreman immediately after this fight can only be described as a nervous breakdown as he thought he was talking to Jesus. A religious conversion followed, and Foreman became a preacher. There was nothing unusual in that. Religion is often the last redoubt of those who fail publicly as a way of saving face. What was unusual was that ten years later, Foreman returned to the prize ring at the age of 37. Ali was retired, and not in the best health. Norton and Frazier were gone too. Foreman would fight for another ten years, his last fight against Shannon Briggs, a loss, in 1997. During this time, he would fight some of the leading fighters of the time including Bert Cooper, Dwight Muhammad Qawi, Gerry Cooney, Evander Holyfield, Tommy Morrison, stunning the boxing world by knocking out Michael Moorer in November 1994 to win the championship at the age of 45. Moorer was nearly twenty years younger and a solid fighter. Moorer was winning the fight when he was knocked out in the tenth round. He likely would have fought Mike Tyson, the biggest name in boxing at the time, had not Tyson gone to prison for rape, which changed the trajectory of Tyson’s career. Foreman did not come back just to win the championship. He actually had another boxing career, fighting 33 times when he returned to the ring. Astonishing.

The new Foreman was pudgy, clean-shaven, bald. His fat, clean face made him seem kinder. His ministry made him less motivated by anger (as highly competitive boxers commonly are): “For me, boxing would have to become the gentlemen’s sport that it was intended to be way back when, and I’d have to win my matches with an absence of rage and a minimum of violence.” (By George, 226) The new Foreman persona made him appear the most fatherly Black man in popular culture aside from comedian Bill Cosby. He began to be used to pitch everything, Doritos, KFC, McDonald’s, Meineke, and Salton’s “George Foreman” Hamburger Grill. No fighter had ever pitched so many products. Ali, Norton, and Frazier only wish they could have. In their era, it was not thought that Blacks could sell products to Whites. In fact, companies hardly thought that Blacks could pitch products to other Blacks. The only Black athlete who could exceed Foreman was Michael Jordan. The Hamburger Grill would become so popular that Foreman was earning over $3 million a month. Finally, he sold his name to the company for $137 million. From his pitchman career alone, he made more money than any boxer, Black or White, in the history of the sport. This was in addition, of course, to the lucrative boxing purses he could command because he was a gate attraction. He became a major presence in two different eras of his sport, after laying out for ten years. It was a monster comeback, an incredible reinvention, from reformed wayward Black boy of the 1960s to blaxploitation cool of the 1970s to Uncle George, a restyled Black advertising icon that updated Uncle Ben to the friendly Black man who lives next door who tells his White neighbor about the benefits of Allstate Homeowners Insurance that one might see on television today. Uncle George with the laughing face! As singer James Brown might have said, “Only in America.”