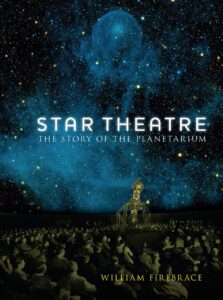

Imagine a book about planetariums written by an architect who retains his childhood sense of awe and wonder for the starry dome, as well as a love for theater. William Firebrace’s book, Star Theatre, is the predictable but delightful outcome. Firebrace artfully describes the drama that plays out in the planetarium, the star theater, as the celestial objects and presenter act out the story of the night sky for the audiences. The book also recounts the history of the human desire to bring the heavens down to earth, recreate their beauty, and replicate their motions.

People who have a fondness for planetariums, astronomy, architecture, or theater could find elements of interest in this beautifully illustrated book. However, professional planetarians and people with backgrounds in astronomy will need to suffer through a few tolerable, cringe-worthy moments where the author shows that his expertise is in architecture, not in astronomy. These include examples such as referring to black holes as dark holes, the far side of the Moon as the “dark side of the Moon,” (131), and planets rotating when the author is referring to revolution. In many cases, the words “rotate” and “revolve” are interchangeable, but in astronomy they are distinct. A planet rotates, or spins, on its axis while revolving, or orbiting, around its star.

People who have a fondness for planetariums, astronomy, architecture, or theater could find elements of interest in this beautifully illustrated book. However, professional planetarians and people with backgrounds in astronomy will need to suffer through a few tolerable, cringe-worthy moments where the author shows that his expertise is in architecture, not in astronomy.

The book seeks to answer these questions: “How and where did the planetarium originate? What kind of simulation of the solar system and the universe does the planetarium produce? How does the planetarium mix theatre with science? How has the planetarium changed with developments in astronomy? What is the relationship between the exterior and interior of the building?” (8) The book is divided into five sections: early forms of simulating the night sky, the invention of the projection planetarium in the 1920s, a comparison between planetariums in the Soviet Union and the United States in the 1930s, the development of planetariums around the world following World War II, and the evolution of the modern-day planetarium.

Theater, or theatre from Firebrace’s English perspective, is another major theme in the book. For the author, the significance goes far beyond the name of the first projection planetarium, known as the Sternentheater, which means “star theater,” in German. Firebrace draws from theater director Peter Brook’s book The Empty Space (1968) to characterize four dramaturgic styles: deadly, holy, rough, and immediate. Especially throughout the first section of the book, Firebrace uses those theatric approaches to examine ways that various cultures have endeavored to understand, model, and illustrate the nature of the heavens. He also compares the planetarium to the theater and movie cinema.

Early recreations of the workings of the stars and planets are suitably described and illustrated in the first section of the book. These include painted domes in the throne room of a king, intricate celestial spheres, and marvelous mechanical orreries. One such orrery would make any genuine astronomy fan jealous—Dutchman Elise Eisinga’s mechanized solar system built into the ceiling of his own living room! Or imagine entertaining guests inside a 3-meter wooden sphere while paintings of the stars and constellation figures revolve around you lit by candlelight. As an architect, Firebrace shares several designs that could never be constructed, such as the mammoth 150-meter sphere pierced with holes to serve as Sir Isaac Newton’s cenotaph.

Of particular interest to planetarium lovers and professionals is the second section of the book recounting the invention of the first projection planetarium in Jena, Germany, in 1923. The story told brings the reader into the Zeiss workshops and rooftop dome, introducing the brilliant engineers who saw a machine projecting light onto a dome as the logical replacement for the proposed complicated machinery consisting of metal globes. Firebrace provides paraphrased and illustrated notes from the Zeiss engineers, and a photo of the Zeiss Mark I projector. The projection planetarium was born, and Zeiss planetariums spread around the globe until the start of World War II.

Firebrace draws from theater director Peter Brook’s book The Empty Space (1968) to characterize four dramaturgic styles: deadly, holy, rough, and immediate. Especially throughout the first section of the book, Firebrace uses those theatric approaches to examine ways that various cultures have endeavored to understand, model, and illustrate the nature of the heavens.

After the defeat of Nazi Germany, the Allies divided the country in two, and the Zeiss company as well. Firebrace contrasts the planetariums built in the Soviet Union with the ones built in the United States both before and after the war, and into the Cold War. The book details how the split in the company plays out in providing planetariums to the Eastern and Western worlds.

The 1960s saw a fundamental change in planetariums. The Zeiss planetariums were expensive, complicated, and accessible only to large, well-funded institutions. Firebrace introduces us to an “unlikely” man (133), Armand Spitz, whom he credits for democratizing the planetarium and making them affordable to modest institutions such as schools. A large portion of the planetariums built in the United States during the post-Sputnik era of the 1960s and ’70s originally housed a Spitz planetarium projector. Firebrace describes Spitz as an ingenious inventor, a showman and almost an American hero of the planetarium realm. What emerges is Spitz’ rags to riches story sounding like the American Dream. If not for Spitz and his rival manufacturers Goto and Minolta in Japan, many people around the world would not have that memorable childhood experience of visiting a planetarium. However, Firebrace, the architect, laments the fact that the democratization of the night sky brought an end to the age of handsome temple-like buildings dedicated to the heavens. He does nonetheless go on to describe several of his favorite exceptions.

Throughout the book, Firebrace’s descriptions and generalizations of planetariums sometimes lack historical reference. One example found early on in the book is the author’s reference to the audience being “seated in a circle around the projector.” (12) While that was common early in the history of planetariums, it is increasingly rare today. Modern planetariums, as Firebrace correctly notes, need to address the rapidly evolving knowledge base of astronomy and cosmology. Today’s planetariums must rise to the challenge of demonstrating concepts that were not yet discovered by the 1920s such as dark matter, dark energy, black holes, superclusters of galaxies—elements that are invisible to the unaided eye.

Modern planetariums, as Firebrace correctly notes, need to address the rapidly evolving knowledge base of astronomy and cosmology.

Firebrace accurately describes present-day digital planetarium projection systems that meet this challenge with their ability not only to show the beauty of the night sky but also to render any image or animation which can be displayed on a computer screen. They elevate the audience from the surface of the Earth to flying them through the solar system and even out of the Milky Way Galaxy. Digital projectors in most cases replace the mechanical projector in the center of the planetarium. The author feels they lack the presence of the optomechanical projector under the dome. Do contemporary first-time visitors to the planetarium miss out on some of the magic of having a mysterious robot in the center of the room beaming the stars onto the dome? It is a fair question.

The author is surprisingly insightful regarding what may be a crucial issue facing modern-day planetariums. What distinguishes movie cinemas from planetariums? Or, in a day when movie cinemas are struggling to bring viewers in from their home theaters, what does the planetarium provide that the movie theater and home theater cannot? Underlying these questions is a longstanding tension in planetariums regarding show formats, live versus prerecorded. To address this clash Firebrace reprises his theater theme, comparing live shows to the theater, and prerecorded programs to the cinema. Prerecorded planetarium programs, like a movie, can be produced using meticulously curated visuals and audio elements with timing fine-tuned to perfection. These prerecorded shows can be presented with consistent quality by lesser-trained staff, reducing long-term costs. Live planetarium programs, like theater, can also be well-choreographed and well-rehearsed, implementing elements of the best visuals and audio effects; they can also be tailored to meet the needs or mood of a particular audience. These live programs require highly skilled and educated presenters, which increases the cost and can limit the number of shows a planetarium can offer. Planetariums can combine live and prerecorded components by having a skilled planetarian present a prerecorded program, providing necessary background information and context for the film, and answering questions after the prerecorded portion, which here again raises the cost of offering the program.

Absent from the book is another question facing modern planetariums. Digital systems are not restricted to simulating the heavens. Many of them have built-in capabilities for teaching other sciences or interdisciplinary concepts. Prerecorded shows are available in all areas of the Earth sciences and beyond. Should planetariums stick to what they are known for? Or should they branch out into a broader array of subjects? The answer is likely to be found in the knowledge and skills of the presenters, and the needs of the institution and audience.

The author is surprisingly insightful regarding what may be a crucial issue facing modern-day planetariums. What distinguishes movie cinemas from planetariums? Or, in a day when movie cinemas are struggling to bring viewers in from their home theaters, what does the planetarium provide that the movie theater and home theater cannot?

Firebrace decidedly favors the live traditional planetarium shows, keeping theatrics in the star theater. He also touches on what may be a key factor for planetariums to remain relevant in a society where most people are carrying a movie theater, maybe even a star theater in their pocket. He describes the planetarium program as a social endeavor, involving a group of people exploring the universe together — a shared experience. Perhaps this social aspect is critical to the movie theater’s relevance as well. The collective gasps, the shared laughter, the question from one person that prompts another: they are all part of the planetarium experience.

Herein lies a valuable lesson for planetariums. Professional content skillfully presented is crucial, but building a community of learners in the audience, building relationships, and setting an appealing social atmosphere are likely to be equally important.

In Star Theatre, William Firebrace, as the architect that he is, provides the reader with an excellent assessment of some of the most interesting planetarium buildings in the world. He also walks us through the unique history of the human desire to bring the heavens down to Earth. However, perhaps his greatest gift is to help us to reflect on what makes the planetarium experience so unique and special. Star Theatre does indeed tell The Story of the Planetarium.