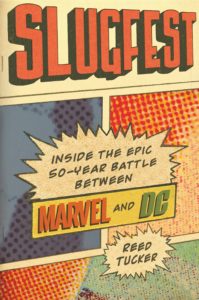

Marvel Comics versus DC Comics. Spiderman versus Superman. Is this like the rivalry between Pepsi and Coca-Cola? Between Birdseye and Green Giant? Between Kellogg and Post? Between Nabisco and Keebler? Between General Motors and Ford? At times, in Reed Tucker’s fanboy account, Slugfest, the battle between the two comic book giants seems more like the squabble between actresses Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, a highly personal catfight between professionals who probably are taking themselves too seriously (is there any other way for human beings to take themselves?) and are too consumed by jealousy (No one really likes someone else’s success). We can throw in the savagery of capitalistic conflict for good measure. As Tucker writes, “As much as readers might like to romanticize the comic book business, it’s still just that: a business.” (xi) He is right to stress that competition often produces innovation but it also can produce destructive waste. Both happened in the comic book industry wars. The fight was, and continues to be, over the stories involving a bunch of physically and physiologically impossible characters—dramatically overwrought, derivative of Jewish, Christian, and Greek mythology, and pulp-inspired—known as costumed superheroes.

The granddaddy, the ne plus ultra, the most famous and recognized of this typology is Superman, created by two Jewish teenagers from Cleveland named Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. Superman, “strange visitor from another planet who came to earth with powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men,” as the voice-over expressed it during the opening of 1950s The Adventures of Superman television show, premiered in DC’s Action Comics in June 1938. The rest, as they say, is history. “Sales of Action Comics climbed month by month, and by 1940 DC was moving 1.3 million an issue,” writes Tucker, “with companion title Superman selling 1.4 million. Stores were also flooded with merchandise, including shirts, soap, pencil sets, belts, and watches.” (6) With the addition of Batman in 1939, and Wonder Woman in 1941, DC had the most popular superheroes, virtual icons of American popular culture. The Trinity, as Tucker refers to them, would be the stars of live-action movies and television programs as well as animated shows.

Tucker is right to stress that competition often produces innovation but it also can produce destructive waste. Both happened in the comic book industry wars.

The popularity of DC superheroes was challenged in 1961, when Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, at floundering, second-rate Marvel comics reinvented its own superhero line from WWII (Captain America being the most famous of this group who would be revived, literally from being frozen in a block of ice, in 1964) with the introduction of the Fantastic Four, a group of astronauts who each were accidentally endowed with a particular superpower and had to learn to cope with it and with one another. Marvel was moved to do this after DC re-introduced a superhero from its WWII days named the Flash which stimulated interest in comic book readers (almost exclusively children) in superheroes again. There had been a dip in comic book reading in the 1950s when comic books were attacked by various civic, religious, and educational organizations as being unhealthy for children. The face of this movement was psychiatrist Frederic Wertham whose book, Seduction of the Innocent (1954), became the basic text of the anti-comic book movement. As in all fanboy histories of comic books, Tucker disparages Wertham, accusing him of having a “demented mind” (103) for pointing out the homosexual subtext of Batman and Robin, which surprised me as I would have thought in this day and age the gay undertones of Batman and Robin’s relationship would be taken as a given, if only humorously. I am also surprised that the blatant racism, sexism, and crude manipulation of the neuroses of children that Wertham accused the comic book industry of would be beyond argument as they are factually beyond dispute. (Seduction of the Innocent came out the same year as the Supreme Court decision to desegregate public schools on the grounds that segregation was designed to make black children feel inferior, that it damaged them psychologically. There was no popular literature which children gravitated to that more tellingly made black children feel inferior than comic books of this era.) Comic book history invariably sees Wertham as a conservative which makes it a liberal duty to attack him. But Wertham was not a conservative, and I suppose not many fanboys have read Ralph Ellison’s essay, “Harlem is Nowhere” or know anything about Wertham’s clinic’s relationship with blacks in New York City.

In any case, the Fantastic Four opened eyes as a fresh way of doing superhero comics. “DC’s heroes were blander, steadier, and less likely to be consumed by their emotions,” writes Tucker. “They had fewer human foibles and little characterization beyond do-gooder, and as a result, they felt more like cardboard cutouts than living, breathing people.” (19) In 1962, when Marvel introduced their flagship hero, Spiderman, a high school nerd bitten by a radioactive spider that endows him with the powers of a spider called to human form, in Amazing Fantasy #15, it was only a matter of time before their line of superheroes would overtake DC’s. Spiderman was that attractive, that appealing, as a new type of reluctant superhero who had to make ends meet, go to school, and deal with an aging Aunt May, the relic of another generation. No superhero comic was more read or sought after among the children I knew, black or white, during my junior high school years than The Amazing Spiderman.

Comic book history invariably sees Wertham as a conservative which makes it a liberal duty to attack him. But Wertham was not a conservative, and I suppose not many fanboys have read Ralph Ellison’s essay, “Harlem is Nowhere” or know anything about Wertham’s clinic’s relationship with blacks in New York City.

Obviously, the concept of Spiderman is simply a juvenile, optimistic, wish-fulfillment re-working of a film like The Fly, released in 1958, which presented the same sort of interspecies “infection”, if you will, as gruesome and tragic. And no, I have not forgotten that there was a superhero character created in 1959 by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby called The Fly, who came into being after a boy rubbed a magic ring and said, “I wish I were the Fly,” and thus was transformed into a muscular adult buzzing around in a green and yellow suit. This was clearly a precursor to Spiderman. Nonetheless, Marvel heroes did seem more real, more interesting, more exciting, their alter egos (when they were not in costume) were more fully developed and not just foils for their super selves as Clark Kent was for Superman or Bruce Wayne for Batman. It is pointed out by more than one observer in Slugfest that DC’s heroes were of an earlier age, created around WWII and enduring largely unchanged since. They emerged at a time of such stalwart, clean-cut western heroes as Hopalong Cassidy (film version, not the novels), Gene Autry, the Lone Ranger, Zorro (clearly the inspiration for Batman), and Roy Rogers, square-jawed detective heroes like Dick Tracy and Bulldog Drummond and actors like Gary Cooper, Joel McCrea, Douglas Fairbanks, Jimmy Stewart, who played straight-forward, unambiguous heroes. Marvel’s reinvention came with the rise of the anti-hero of the 1950s, actors like Marlon Brando and James Dean, characters like James Bond, and the complex Sergio Leone and Anthony Mann westerns. But even with the changes that Marvel wrought, their superhero characters were still meant for children or adolescents. Even with Marvel, it was expected that children would eventually outgrow comic books, and most did. I remember it was the summer when I was 13 that I stopped reading superhero comics cold turkey. That summer I read Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki (1948) and Richard Wright’s Black Boy (1945) and superheroes suddenly seemed silly. Their plots were repetitive, with fist fights where no one ever was really hurt, evil and good were calibrated in ways that had nothing to do with the conditions and politics with which people really had to contend. I had never read a comic book that was remotely as good as those two books I read that summer.

And this is the important point: as fanboys who grew up reading Marvel in the 1960s began to take over the industry as writers, artists, and editors in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, they were determined not to outgrow comics, but simply to make them more “adult” with more sexual and violent content, a kind of modernized pulp. This “Peter Pan” desire never to outgrow the medium, always to have your childhood pleasure give you pleasure for the rest of your life, reflected the phenomenon of the ever-lengthening childhood and youth that seemed to increasingly characterize American life. Did superhero comics, by adding noir-ish effects, become more mature or did they simply disguise how they stunted the maturity of their audience by falsifying or straining the concept of their superhero characters? Why did the comics have to be more mature or seem more mature? Why did the fanboys who took over the industry feel it was beneath them to write for children? What is wrong with writing for children? Why do many people consider it a “lesser” enterprise? Slugfest explains the changes in the industry but never explores why they happened or what larger cultural questions or cultural crises were reflected in the need to change superheroes or even to continue to have a creative interest in them. Obviously, money played a role because these characters were so widely recognized, so familiar to large portions of the public, but money by itself is no guarantee that anything is going to survive, or that it should.

Did superhero comics, by adding noir-ish effects, become more mature or did they simply disguise how they stunted the maturity of their audience by falsifying or straining the concept of their superhero characters?

Once the origin story of Marvel is told, Slugfest becomes a series of gossipy testimonials from artists, writers, and editors who worked for both DC and Marvel (there was a great deal of professional exchange, or incest, between the two) about Marvel’s unstoppable, juggernaut success, beating DC at every turn, outselling them in the comic book realm, being more highly regarded among the true believers in the comic book reading world, having greater success with their movies. (Scanning the lists of the top-ten highest grossing movies of the last five years, including 2018, finds that Marvel superhero movies have made the lists 13 times, DC only three.) Tucker’s work is quite informative and even engaging. Slugfest reads a bit like penetrating a cult that has an influence far beyond anything by rights it should have and one is a bit puzzled as to why it has the hold on the culture that it does. It is a fun book for anyone interested in comic books, in American popular culture generally, or in the obsessive and sometimes pathological nature of business competition but it is not the incisive book about this industry that still awaits its author.