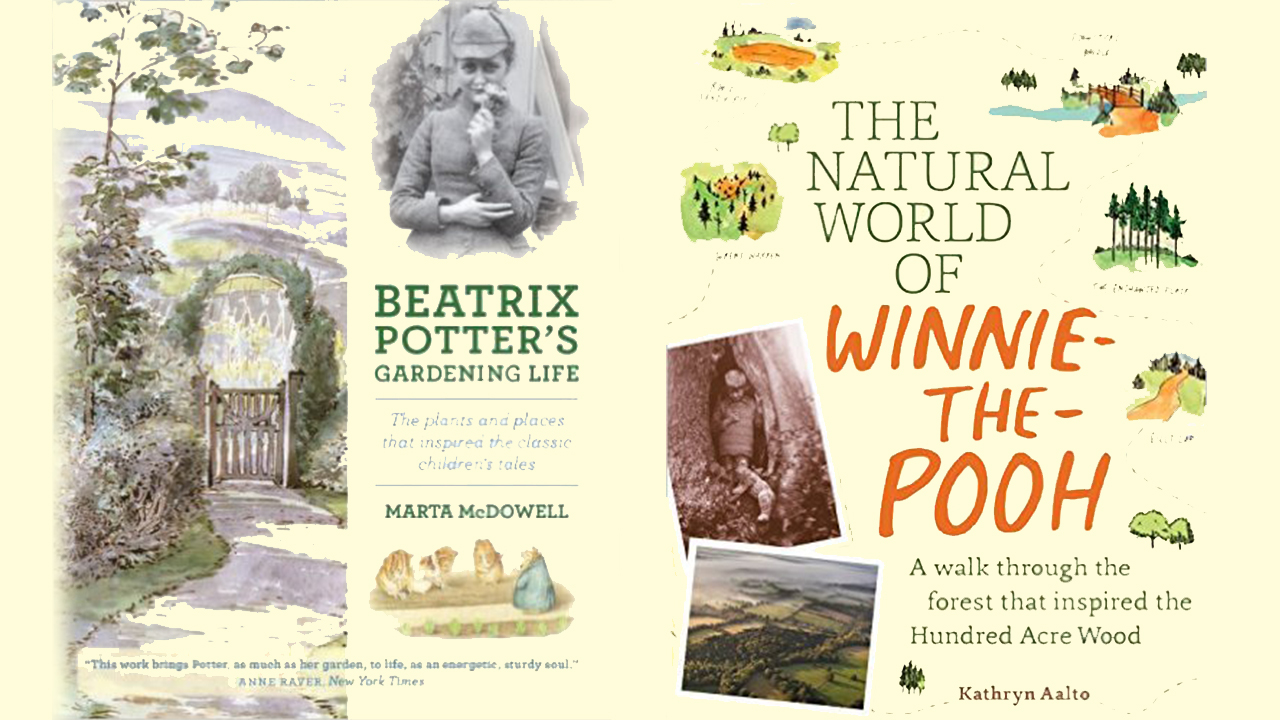

• Beatrix Potter’s Gardening Life: The Plants and Places that Inspired the Classic Children’s Tales

By Marta McDowell

( 2013, Timber Press) 339 pages including illustrations, charts, photos, bibliography, notes, and index

• The Natural World of Winnie-The-Pooh: A Walk Through the Forest that Inspired the Hundred Acre Wood

By Kathryn Aalto

( 2015, Timber Press) 307 pages including bibliography, notes, illustrations and photos, and index

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

—Seamus Heaney, “Digging”

McDowell’s and Aalto’s respective books, published by the same press within two years of each other, are impressive studies of the relationship between literature and landscapes both emotional and physical. The goal of each is to give a reader devoted to the literary life of an Edwardian Giant of Children’s Literature a glimpse of the landscape that both shaped that life and is featured in the literary work. In these two books we are given Milne’s forests and Potter’s gardens—two sites available for literary pilgrimage. Both Aalto and McDowell dig with squat pens into research and soil: the harvest is two fascinating books by ardent enthusiasts of nature and the enduring innocence of children’s literature in a bygone age.

These books share a great deal; perhaps most noticeably they are lavishly produced. These seem meant to compete with Better Homes & Gardens on your living room coffee table. The glossy pages have one or more pictures on just about every two-page spread, and a generous portion of pictures that take over the entire spread. The volumes reward a serious browse with gorgeous pictures of natural landscapes, buildings, and contain many charts, maps, and tables.

Marta McDowell’s study of Beatrix Potter’s gardens and gardening life came out first. McDowell, whose life is chronicled on her blog, teaches landscape history and horticulture at the New York Botanical Gardens, and so she knows a few things about flora. Confessed to be “intrigued by writers who garden and gardeners who write,” she is the author of a previous study on the subject: Emily Dickinson’s Gardens: A Celebration of a Poet and Gardener (McGraw-Hill 2005). The idea for the Potter project simmered in her mind for years and, seems, finally boiled over. The book is organized into three successively smaller parts. Part one is a 130-page gardening biography of Beatrix Potter divided into metaphors of plant growth: Germination, Offshoots, Flowering, Roots, Ripening, and Setting Seed. Part two is a seasonal study of the plants in Potter’s gardens with winter leading the way. The third part is a look at today’s settings for the various places Potter gardened.

The lead up to the first section gives readers a sense of McDowell’s presentation of Potter’s life. Before part one there is an introductory page in which the author indulges in a lengthy scene set off in italics. It is dramatic and in present tense, a sign of a style she uses later in the book:

A woman walks up a rise toward a farmhouse, tape measure in hand. She is small in stature, and some gray hairs are wound into her otherwise brown bun. […] Beatrix Potter can picture the garden built and full of flowers: snowdrops in winter, a spring torrent of lilacs and azaleas and daffodils, summer covered with roses, chrysanthemums for autumn.

Beatrix Potter is not just McDowell’s study but a character in her story of gardens. Potter is a vehicle for McDowell to wander about particular gardens and make observations about them. There is an ease in the story-telling in this book, a comfortable authority. An example of where McDowell weaves chronology and research into story-telling is on page 44:

In the course of the familial peregrinations, Beatrix Potter began to appreciate gardens in a new way. Her father taught her the basics of photography and gave her a camera. Among her exposures and his are many landscapes and designed outdoor spaces. In Salisbury she admired the Cathedral Close, “with its fine elms, green meadows and old red-brick houses in gardens where the Ribes and Pyrus japonica are coming into flower.” Years later she would plant goose berries and currants, both Ribes, and japonica in her own garden.

This is typical of the book. McDowell wants to go beyond accounting and cataloging to show us the story and development of a writer and gardener.

The first part is a story of places and their impact on the young Beatrix. Here McDowell recounts the environs at Camfield (the paternal grandfather’s holdings), Dalguise House (a Scottish manor house at which the Potters spent 11 holiday seasons until she was 16), Bolton and Kensington Gardens in London where the family had a home. “Beatrix developed her inner gardener on the three-legged stool of South Kensington, Dalguise, and Camfield Place.” Before young Beatrix became an accomplished gardener, she drew her landscapes. Early in her life she worked at illustrating flowers and fungi with the hope of contributing her skills to those publishing scientific work on botany. “It is easy to envision a different path for Beatrix Potter,” McDowell teases. “With more encouragement at Kew or the Linnean society she might have become an illustrator of botanical books, in the legion of Victorian women who painted plants. Even she could see it.” An early setback in her scientific illustration career turned her toward a different path, however. Science’s loss is the child’s gain, it seems.

It is in the chapter “Flowering” that we are introduced to Beatrix Potter’s burst of creativity that saw the publication of Peter Rabbit and other early books. Here McDowell studies the flora and fauna represented in those books, noting how gardens are prominent in the early bunnies books (The Tale of Peter Rabbit and The Tale of Benjamin Bunny) while The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin and The Tailor of Glouchester feature forest and city. In The Tale of Peter Rabbit we are told of Mr. McGregor’s likely subordinate status on the land, the way of cucumber frames, the practice of using a “dibbler” to “plant out young cabbages,” and the particular use of hoeing to cultivate onions. This is all news to an inveterate “indoorsman” like me. We see how the place where Beatrix resides at the time of writing is reflected in a tale, as her time in Fawe Park in the summer of 1903 “matches the Benjamin Bunny illustrations in lockstep.”

Clearly it is a gardener’s book, but it is a gardener’s story about a gardener—a writer’s story about a writer. It is lyrical as well as biographical as well as botanical, and in this way it is itself literary.

It is also in the section “Flowering” (arguably the richest and most interesting section of all) that we learn of her engagement to her publisher Norman Warne and his unfortunate passing a month after their betrothal. Important to this story is that it was but two months later that Beatrix bought Hill Top Farm, the 34 acres of which she would cultivate all the rest of her life. Hill Top, purchased and renovated with the proceeds from her successful early books, “is in a distinct genre that emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,” which is a “vernacular gardening style … combining traditional materials, informal dense plantings, and a mixture of ornamental and edible plants.” Her remaining books would find bits of Hill Top depicted in them. For instance, “Beatrix shares much of the front garden at Hill Top with her readers” in Tom Kitten’s story. The Tale of Jemima Puddleduck features a walled vegetable garden at Hill Top, the beehive from her yard, and her prized rhubarb. “Beatrix’s favorite sheepdog, Kep, is the hero of the story.”

The second part of the book features 90 pages of “The Year in Beatrix Potter’s Gardens” through the seasons. Here McDowell becomes especially lyrical. Following the observation that no garden journal that Beatrix Potter may have kept was ever found, the author takes the opportunity to imagine one of her own using the seasonal realities of Hill Top and Castle Cottage, Potter’s own correspondence and art work, written memories of others, and photographs as the foundation. We are presented with an imagined Beatrix Potter: as she is “walking back from the barn, her eyes absorb the silent snowy landscape reflecting blue light.” As she walks, she “listens for the first cuckoo call,” and “little bulbs that would be overlooked in the peak season have their day. The snowdrops are improbable if not preposterous.” McDowell even imagines the interior life lived in winter, for instance: Beatrix reading through seed catalogs on a cold day. In autumn, “home from the fair, she walks through her garden. Creepers on the walls are coloring. Michaelmas daisies bloom like a galaxy of stars, backlit in the luminous afternoon.” McDowell uses present tense descriptions to make readers visualize Beatrix and themselves together engaged in her gardens.

The book’s last main section, “Visiting Beatrix Potter’s Gardens” focuses on the various sites important to Potter in their current state today—something of a 20-page written and visual tour of “what’s it like there now?” Close on its heels comes an impressive collection of information about the books and places, and we move from the lyrical to the categorical. The first list of plants is six pages of plants that could have been found in her gardens; these are listed in alphabetical order by common name followed by botanical name (Potter’s own preference was the common name), the type (perennial, shrub, fruit, veg, biennial, vine, feed crop, tree), primary source (letters, recorded memories of friends and family, other printed accounts); 12 pages of plant references in the children’s books follows, organized first by chronological publishing history and including common name, botanical name, and then clarification of whether the plant was mentioned in the text and/or rendered in the art. The Notes on Further Reading following this section is very thorough.

This book is best appreciated by a gardener and then by someone who cares about Beatrix Potter. Clearly it is a gardener’s book, but it is a gardener’s story about a gardener—a writer’s story about a writer. It is lyrical as well as biographical as well as botanical, and in this way it is itself literary. All that said, I am not a gardener, but I enjoyed this book in part because McDowell welcomes me in through careful exposition. The book does not exclude. My wife, who is a gardener, waited patiently for me to finish this. I enjoyed McDowell’s playful and dramatic language. My candidate for the best sentence in this book is a description of how the character Mrs. Tabitha Twitchit, errant child on her lap, “inflicts corporal punishment to a floriferous backdrop of irises and peonies.”

• • •

Kathryn Aalto’s written and pictorial homage to A. A. Milne, E. H. Shepard and the land they depicted is equally playful, dramatic, and visually stunning. Aalto’s book also is divided into three sections following the introduction. It is in the introduction that we see Aalto’s enthusiasm for her subject. She wants the reader to revel in the settings that inspired the books, which “are bound in nostalgia for bygone days;” and like McDowells text, Aalto’s is rich in photographs of current sites, maps, historical photos, and artist’s renderings. Like McDowell, Aalto is prepared to come at her subject from a couple of vantage points as she has degrees in English, garden design, and history (see her blog). Aalto describes her approach to her subject this way: “As a landscape historian and designer, I am trained to read the landscape like a text and to unfold narratives of the past through research, interviews, and photographs. I also know when it’s time to chuck books for boots and go outside for a walk.” Like Milne in his own books, Aalto is a highly perceptible narrator: she is present in the writing as she is present and writing in Milne’s landscapes. “This book is the result of passions for walking, landscapes, and literature,” she writes—“all things Milne loved and celebrates in his writing.” As it is in McDowell’s book, in The Natural World of Winnie-the-Pooh the subject is an object of identification for the author. Aalto’s writing is direct and natural, even a bit romantic and wide-eyed in its fandom at times. This is hardly a problem given that her implied reader is clearly someone who is assumed to be as excited about the prospect of playing Poohsticks as is she, if that is possible. The book’s tone is infectious; she really wants you to see it as she does.

The book makes the reader hear the voice of the docent who points and says, “and here, you’ll be interested to know, is where … ” It is a lovely impression, really.

The first part, “Creation of a Classic: The Collaboration of A. A. Milne and E. H. Shepard” is mostly about Milne’s outdoor childhood and its lasting effects on his life and writing for children. The collaboration with Shepard is mentioned in the closing pages and explains the very happy working relationship between the two. Milne was very pleased with Shepard’s work, and it was important to Shepard to “get it right” as it came to the rendering of Cotchford Farm, Ashdown Forest, and the Five Hundred Acre Wood—the sites of the stories in Milne’s imagination. Shepard’s illustrations are not generic woods; they are clearly place-based. Aalto rightly claims that the “books are a pitch-perfect collaboration and sensitive interplay between artist and writer.” While much of the biographical information is not new and would be familiar to readers of Ann Thwaite’s biography (A. A. Milne: His Life, Faber and Faber, 1990), the point here is the focus on Milne’s (and his son’s) relationship to the landscape.

In the second part of the book—the bulk of her project—Aalto takes us on a tour. “Exploring the Hundred Acre Wood: Origins of the Stories” is a walk through Hartfield Village, Ashdown Forest, and Cotchford Farm. She invites us to go on an “Expotition” (a Winnie the Pooh-ism for expedition) to Milne Land:

But why not start at the place where the stories originated? That would be Cotchford Farm. From his bedroom study there, Milne would walk downstairs to the hearth in the sitting room, where he read aloud drafts of the stories to his wife and son. We will first tour the house and garden, and I will tell you stories about this place and that place which influenced the stories. We can then go on an Expotition and amble down Jib Jacks Hill to Hartfield and then farther afield. I’ve put some Provisions together—a thermos of tea and a little smackerel of something. You just need a waterproof hat, waterproof boots, and a waterproof macintosh. This is England, after all.

And so we pack up and follow. Along the way we find what is conjectured to be the model for Pooh’s house—a centuries-old walnut tree with a hollow center and gash-for-door. We see what Christopher Milne claims to be The Trap for Heffalumps spotted where a sundial stood between Cotchford Farmhouse and the old walnut tree. We are invited to conjecture about where the woozle was not and where Eyeore’s gloomy place is. We are shown the likely bee tree. Owl’s house was based on a particular chestnut tree in the five hundred acre wood which disappeared during World War II. The Sand Pit is found in a general area in Ashdown Forest. Rabbit’s house is based on artificial rabbit warrens fashioned in medieval Ashdown Forest (we get a brief history of rabbits in England as part of the price of admission on this tour). The Enchanted Place is a particular cluster of trees presumably planted intentionally to break up the landscape. The book makes the reader hear the voice of the docent who points and says, “and here, you’ll be interested to know, is where … ” It is a lovely impression, really.

Sometimes Aalto blurs the line between history and fancy regarding what location inspired what story setting to the point where she says, “Does it matter?” It all depends whether you are on the tour for history or imagination … or some combination of both. I think the author is interested in that combination. Knowing that there is a history for the link between the area and the imagined land of Pooh, it frees her to speculate. So, knowing that Christopher Milne identifies Wren’s Warren as where the North Pole is discovered makes us willing to identify likely places for Pooh’s Thoughtful Spot. A sensible conclusion about Piglet’s house is that it was “probably inspired by a beech where the forest meets the private land” because of where one would find trespassers warnings. Other things are worth noticing: “Like a Thoughtful Spot in a fictional forest, the Stepping Stones could have originated anywhere,” but again she draws us toward the landscape and Milne’s own devotion to its description. Yes, the Stepping Stones could be anywhere, but pay attention to the natural world in the description. Aalto helps us realize that

Some of Milne’s most lyrical and beautiful writing comes when he describes water. It can be playfully swirling around stones or personified as a child enjoying the sunshine. Throughout the stories, in a paragraph here and a paragraph there, his descriptions of water are exquisite: at one time, a little stream dances and moves like an eager, impatient child. Other times, energetic rivulets high in the Hundred Acre Wood flow into a thoughtful and mature river much in the way we move into adulthood and finally settle down.

She, like Milne, becomes most lyrical when she is engrossed in natural wonders, especially as they connect real place to the imagined land of Pooh.

Sometimes Aalto blurs the line between history and fancy regarding what location inspired what story setting to the point where she says, “Does it matter?” It all depends whether you are on the tour for history or imagination … or some combination of both. I think the author is interested in that combination.

The third part, “A Visitor’s Guide: The Flora and Fauna of Ashdown Forest,” is a tour of the region’s history, both natural and societal. Here Aalto wants us to understand what went into the development of the place and what it looks like today. She offers the reader some suggestions for how to be a good visitor as you look about. We are given surprisingly specific information, such as the fact that there “are thirty-four recorded species of butterflies in Ashdown Forest, bringing color and sparkle to the forest like flowers with beautiful wings.” Aalto’s lyricism continues into this third section, as you can see, and the subject about which she is most enamored—charmed, actually—is the Poohsticks (or Posingford) Bridge.

The largest section devoted to the game is found in this third part, but over twenty pages are devoted to the place and pastime. When she says that “Giving our children the real Poohsticks experience feels like providing them with an important cornerstone of childhood,” she is not messing around. She retells the tale as part of the description of places in the book; she later describes a round played in the visitor’s guide section, later she provides a full history of the bridge (there have been three on the site), opines on the best times of year to play, and then describes the World Poohsticks Championship, which is an actual event. There are ten pictures devoted to Poohsticks throughout the book. This woman loves her some Poohsticks.

Like McDowell’s book, Aalto’s provides the reader with no shortage of resources. There is even a metric conversion table to help American’s understand how far things are from each other. She provides a comprehensive bibliography of Milne’s work, sources related to her discussion of history, geography, geology, botany, and more, and a very useful index (in which you can find all the reference to Poohsticks, for instance).

These are two wonderful, leisurely experiences in history, botany, and literature. Leisurely for us, though clearly a lot of hard work for McDowell and Aalto (though the love of the work emanates from the pages). I recommend them as winter evening reads before the fire as you thumb through seed catalogs, The House at Pooh Corner, and The Tale of Benjamin Bunny. I promise you it will all come together.