“Roger Moore is a much better actor than he ever gives himself credit for and although it’s hard to believe, he has little confidence in his own abilities. There were occasions when I had [to] take him to one side and give him pep talks, saying ‘Roger, you can do this, you really can.’…

Roger was a pleasure to work with because he was so professional—I don’t think he ever fluffed a line. … The Bond films don’t always use the most experienced actresses—looks can be just as important as ability—and there were occasions when Roger would patiently feed the girls the lines off camera while they tried to get it right for their close shots. Sometimes this would continue for take after take, and I should think Roger was mentally exhausted at the end of some days.”

—John Glen, For My Eyes Only: John Glen, Director of Five James Bond Films (123, 135)

1. The unstoppable popularity of the “stupid policeman”

Live and Let Die, the 1973 Harry Saltzman and Albert “Cubby” Broccoli film version of the 1954 Ian Fleming novel of the same name, was something like the second reboot of the James Bond film series. That is, if having a different actor play Bond is considered a reboot. Scottish actor Sean Connery established the role in 1962 with the highly successful Dr. No and went on to play the character four more times—From Russia with Love (1963), Goldfinger (1964), Thunderball (1965), and You Only Live Twice (1967). He then left the series, having fulfilled his original contract of doing five films, preoccupied with grave fears of being type-cast as the violent, highly loyal in a public schoolboy way, wickedly resourceful, abundantly skilled, womanizing British secret agent, “a stupid policeman,” as one of Bond’s enemies characterized him. Connery did not want to wind up like Johnny Weissmuller, who played Tarzan in twelve feature films and went to play Jungle Jim, a sort of Tarzan with a pith helmet. Probably Weissmuller, a champion athlete before becoming Tarzan, did not mind being typecast.

An Australian model named George Lazenby took Connery’s place in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), and promptly quit after completing the film, thinking Bond an anachronism, a completely dated character, and that the series had gasped its last breath. This thinking was not presumptuous; it was, in fact, considering the political tumult afflicting Western culture in the late 1960s fairly sensible. Why would some sexist, potboiler fictional relic of the 1950s version of the Cold War be appealing to movie audiences during the age of Black Power, the New Left Revolution, the fiasco of the Vietnam War, and the rise of feminism? Moreover, this film did not do nearly as well at the box office as the previous Bonds. Was it solely because of the actor playing the character, or because of the character himself?

Why would some sexist, potboiler fictional relic of the 1950s version of the Cold War be appealing to movie audiences during the age of Black Power, the New Left Revolution, the fiasco of the Vietnam War, and the rise of feminism? … Was it solely because of the actor playing the character, or because of the character himself?

As it happens, Lazenby’s thinking may have been reasonable, but it was to be dreadfully wrong. The fact that On Her Majesty’s Secret Service was the least financially successful of all the Bond films compelled the producers to talk Connery “out of mothballs,” so to speak, (with a huge salary) to reprise the role in Diamonds Are Forever (1971). This film garnered the sort of box office returns that the Bond producers were more accustomed to, but Connery swore he would never do the role again. (That turned out not to be true but, alas, that fact is not germane to this review.) So reboot one with Lazenby did not work and Connery was brought back temporarily to save the franchise. But despite the film’s success, the fact remained that the character and concept still seemed dated. Diamonds are Forever was released the same year as Don Siegel’s critically and commercially successful Dirty Harry, a dark film about crime and the decay of the American city featuring a tough San Francisco cop (Clint Eastwood) who carried a .44 Magnum, tortured criminals for information, and thought little of constitutional provisions such as due process. It was a film like Dirty Harry, that seemed to speak more to and for the anxieties and fantasy resolution of those anxieties of the period than a James Bond adventure. Nonetheless, Bond endured. Enter Roger Moore and reboot two.

2. The reinvention of the “stupid policeman”

Why not Moore? He had a number of advantages over Lazenby, foremost being that he was a professional, experienced actor. On British television between 1962 and 1969, Moore played the Saint, Leslie Charteris’s famous pulp do-gooder rogue played in the 1940s on screen by George Sanders. So, Moore played an action hero with some similarities to Bond; indeed, a few of the episodes of The Saint make fun of this by having the character mistaken for Bond. Moore was familiar to American audiences because The Saint was successfully aired in the United States. (He also appeared in the American television series The Alaskans in 1959-1960 and as Beau Maverick in 1960-1961 in the American television western, Maverick, which had made a star of James Garner. Incidentally, Moore’s role in the series had first been offered to Connery.) Moore was a plausible choice to be Bond, possessing sufficient skill and fame to replace Connery. He also possessed a quality that Connery lacked, an ability to do light comedy well. Moore had the face for it because he could make his eyes twinkle mischievously and smile boyishly; Connery could not. For instance, the opening of nearly every episode of The Saint had Moore speaking directly to the camera, breaking the fourth wall, as it were, when someone finally formally identifies him as Simon Templar and a halo appears over a somewhat amused Moore which cues the theme music. Connery was not the sort of actor who could have pulled that off nearly as well. Moore was no Cary Grant, but he brought to the Bond character qualities that Grant probably would have. (By the way, Grant was the first actor to be offered the role of Bond in Dr. No.)

Live and Let Die was the perfect vehicle to reboot Bond with Moore. It was the only Bond with what used to be called in the movie business when I was a boy, “an All-Negro cast,” or nearly so. The novel is a lurid tale about a Black gangster named Mr. Big (thank goodness, he was not named Mr. HNIC, vulgarly decoded among Black folk as “Head Nigger in Charge”) and his operations in New York and Jamaica as an agent for the Russian intelligence agency, SMERSH, whom readers meet most famously in the novel, From Russia with Love. (This was changed in the film to SPECTRE, so remove it a bit from Cold War politics.) There are a bunch of ridiculous (and, more importantly, childish) names for the Black characters such as Tee Hee, Whisper, and Blabbermouth—names only a White author of a certain era would think Black people would actually possess. (I will leave it to some literary critic to discuss the use of the names as deploying ironical exaggerations of human speech. Art is as smart as the brilliant critic who tells you what it means!) Mixed into this cauldron of a coon show are voodoo and zombies. (This is back in the day when zombies were connected in popular culture to Haitians, dolls stuck with pins, and some choreographed sexualized flapdoodle that was meant to resemble Black religious culture in the Caribbean. Old-school zombies did not eat people. For examples, see such films as the 1943 classic I Walked with a Zombie, and Macumba Love, 1960.)

Live and Let Die was the perfect vehicle to reboot Bond with Moore. It was the only Bond with what used to be called in the movie business when I was a boy, “an All-Negro cast,” or nearly so.

Live and Let Die became, in effect, the James Bond pseudo-Blaxploitation, counter-Blaxploitation flick. Urban-situated, graphically violent, and sexual Black cast films where the Black hero beats the criminal “whitey” and cleanses the ghetto of him were popular with young Black audiences in the early and mid-1970s. Live and Let Die has elements of Blaxploitation but reverses the polarity so that the White hero beats the Black criminal and saves the White girl from his evil Black clutches (Shades of Birth of a Nation!) The film gives us the old, racist narrative but decked itself out in new urban, Black cast clothing with a touch of the Louisiana and Caribbean thrown in for Black Diasporic flavor. Imagine Tarzan without a loin cloth and that, in one respect, sums up this film. It was a smart move; a Blaxploitation movie average Whites would like. Lots of Blacks saw the film; at least a lot of Black people were in the theater the day in 1974 when I saw it. I guess we enjoyed it, or we were at least used to this sort of thing.

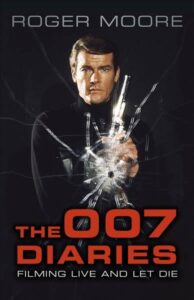

As Moore had committed contractually to more than one Bond film, the reboot was meant to be a true reinvention of the series. The 007 Diaries signified that break, the end of Connery as Bond; it is Moore’s day-by-day account of the filming of Live and Let Die. It is a vivid, rich account of how a Bond film is made, the grueling pace, the boredom, the physical risks, the over-eating and marathon drinking, and the sense of community among the people involved: in short, filmmaking on this level is revealed as both a nearly heroic exercise in tenacity and an astonishingly pure expression of absurdity. It is fascinating to read as a companion to Charleton Heston’s The Actor’s Life: Journals, 1956-1976 (1978). For Bond aficionados, Moore’s book nicely complements John Glen’s For My Eyes Only: John Glen, Director of Five James Bond Films (2001). Glen directed Moore in For Your Eyes Only (1981, considered by critics to be the best Bond film with Moore), Octopussy (1983), and A View to a Kill (1985). He was also a second unit director and editor on two other Moore/Bond films: Moonraker (1979) and The Spy Who Loved Me (1977). Glen also oversaw the next reboot in the Bond series as he directed the two Timothy Dalton/Bond films: The Living Daylights (1987) and License to Kill, (1989), the latter Glen considered the best of all the Bonds he worked on.

The 007 Diaries covers eighty-four days of shooting in New Orleans, the Louisiana bayous, Jamaica including a crocodile farm in San Monique, Pinewood Studios in England, and New York City, particularly Harlem. Not only is there a huge film crew of actors, technicians of various sorts, stunt people, and support staff but, as Moore points out, “photographers, television crews and documentary film crews from all corners of the world.” (34) The fact that a new, well-known actor is playing Bond is big news. And there are the locals, some with functions; some just rubbernecking. Moore remarks: “Our caravan of spectators gets larger and larger. I spend more time signing autographs than I do chasing villains.”(28) But it is the acting that is uppermost in Moore’s mind: “The pressure of being Bond grows daily. Not in playing the part, but in being the actor playing the part.” (31) He is constantly interviewed, and asked the same question: “The question that still rolls at me as relentlessly as the camera is: ‘How is your Bond going to be different from Sean Connery’s Bond?’” Moore writes, “I am absolutely fed up with being asked that and I have, at last, thought of an answer. I will ask writers how their column is going to be different from everybody’s else column.” (94) No journalist quite thinks of him as the “real” Bond; most seem to think that Connery’s Bond cannot be equaled and that is nearly sacrilegious for the characterization to be altered which a new actor is professionally required to do. Moore as the pretender to the throne soldiers on.

Moore documents that there is a fair amount of racial tension on the set. For instance, co-producer Harry Saltzman has to be reminded not to call a White prop man by the nickname “nigger,” especially with so many Black people on the set. (38-39) Then, there is bitterness between the Black and White stuntmen: “There were angry mutterings today from some of the Black stunt boys when Joie Chitwood’s team, Blacked up and bewigged, were chosen to stunt the spectacular skidding and crashing of planes and cars. It is understandable that Joie wanted his own boys, but the Black team was very angry and nobody is quite sure what will happen tomorrow.” (53) And during a publicity photo shoot, Black actor Yaphet Kotto, who plays the villain, Mr. Big, “was punching the air with a Black Power salute. Whether he was serious or not, I don’t know, but the sequel was a scorching row.” Publicity director Derek Coyte rebuked Kotto for, in effect, suggesting that Live and Let Die was “a political picture”1 and that photos of the Black Power salute could cause resentment among “the rabid whites” and harm the reception of the film which would serve no good purpose for anyone. “Yaphet was incensed,” Moore writes. And the Blacks and Whites lunched separately on the set that day. (60) Later, Moore writes about the incident: “When Yaphet Kotto came to New Orleans and gave the Black Power salute, there were those who said he had a chip on his shoulder. As a Black actor in a predominantly White industry, perhaps he believed he had to assert himself.” (163) But Moore continues by saying how well Kotto acquitted himself as an actor in the film and that the best role in a Bond film is the villain who invariably gets the best lines such as the “stupid policeman” crack in Dr. No. And there are problems shooting in Harlem: “Driving uptown to Harlem was an eerie experience. There is no welcome for whitey there; suspicion stalks the streets, and, contrary to our usual experience, no crowd collects to stand and stare at the film crew at work. The streets look empty and forlorn, given over to grinding poverty, soaring crime, and the deathly delusion of drugs. … We began filming in an uneasy state of truce: the path carefully paved and the word out, but, should the message have failed to filter through, six armed Black policemen were stationed around the set and a squad of Black Muslims in separate groups stood a few yards from the camera. The Muslims are purportedly to help with crowd control, but in fact are appointed by the precinct mosque for our protection.” (2020)

As Moore had committed contractually to more than one Bond film, the reboot was meant to be a true reinvention of the series. The 007 Diaries signified that break, the end of Connery as Bond; it is Moore’s day-by-day account of the filming of Live and Let Die. It is a vivid, rich account of how a Bond film is made, the grueling pace, the boredom, the physical risks, the over-eating and marathon drinking, the sense of community among the people involved …

Life for a lead actor like Moore in an expensive A-list production like a Bond film has its stresses: Moore was injured almost as soon as filming began while doing a motorboat-racing sequence. The innumerable exhausting takes. The long hours on the set. The daily changes in the script and the need to learn new lines almost immediately. Acting in a film like this is challenging physically even with the extensive use of stunt replacements. And then there is the time when replacement by a double is a cause of embarrassment for the star. In the scene where Bond is about to be bitten by a snake in his Jamaican hotel room but has the presence of mind to ignite the spray from his aerosol with his cigar and burn the critter to death there is a cutaway to Bond’s bare feet. They are not Moore’s feet but a double’s. And the double happens to have noticeably flat feet. Moore, who does not have flat feet, was more than a little chagrinned by this. To think that James Bond has flat feet! But there are compensations: well-stocked, luxurious trailers, private air travel, limousine service, five-star hotels and restaurants, convivial gatherings with other A-list movie people who happen to be visiting.

The 007 Diaries is competently written, carrying the reader along day-by-day without flagging. A nice read for Bond fans, movie aficionados, wanna-be actors, and those who wish to remember the good work of Roger Moore. Live and Let Die was a big hit, helped in no small measure by the success of the theme song by Paul McCartney. Moore went on to play Bond in six more films, more than Connery did for Broccoli/Saltzman. In fact, more than any other actor who played the part. (Connery’s final turn as Bond in 1983 in Never Say Never Again was not a Broccoli/Saltzman production and is not part of the official Bond series.) In this sense, Moore may have left a larger mark on the series than Connery did. Good for him.